Fall 2024

Building with Bagasse

A Marrero company found sweet success with sugarcane fiber until the walls tumbled down

Published: September 1, 2024

Last Updated: December 1, 2024

Lucie Monk Carter

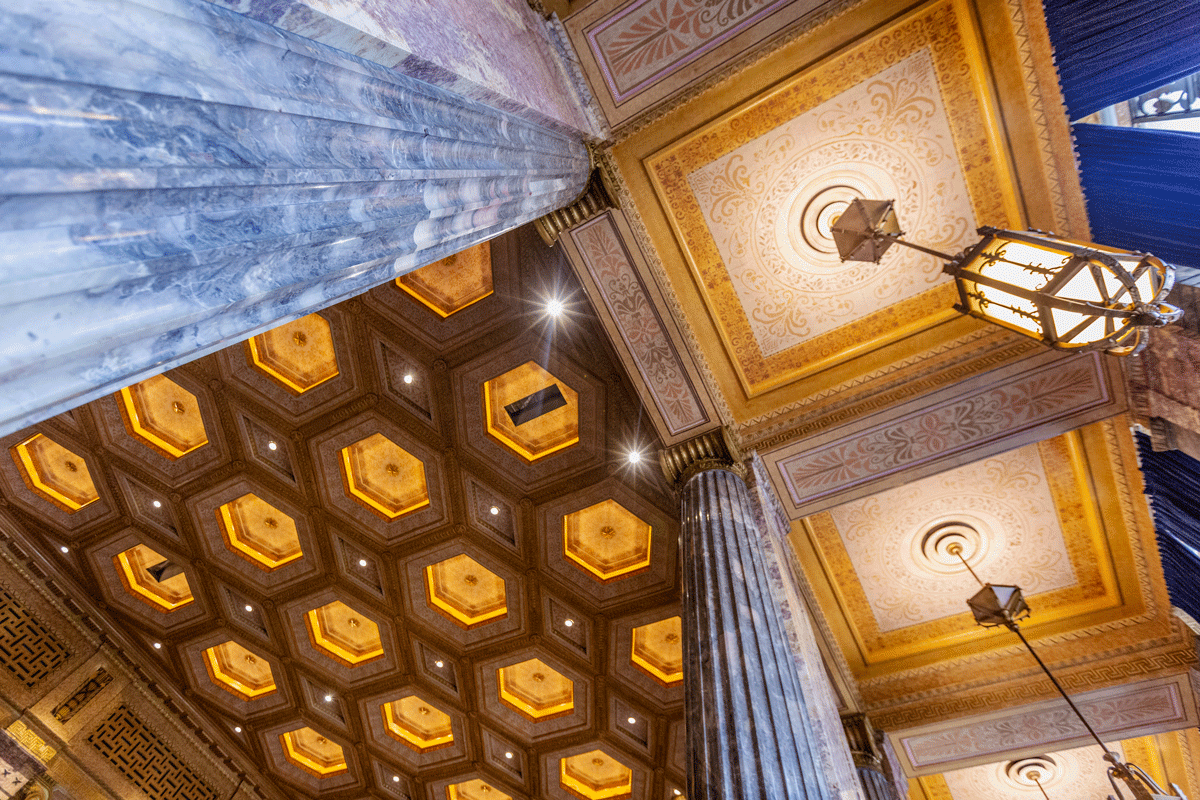

The ceiling of the Louisiana State Capitol Senate Chamber, made from sugarcane byproduct at the Celotex Company plant in Marrero, Louisiana.

Inside the Senate Chamber at the Louisiana State Capitol, marble columns stand as wide as small cars. Across a grand entrance hall, the House Chamber gleams with richly veined stone walls and pilasters. Elaborate ceilings in both rooms, though, nearly steal the show. Above state senators’ desks, sixty-four recessed hexagons centered by a star represent the state’s parishes. In the House’s workspace, art deco designs in lush earth tones stretch overhead from wall to wall. The stones in those chambers originated in Italy, Germany, and France. The ceiling material traveled a much shorter distance. It came from Marrero, just down the Mississippi, and it holds a history more suited to those imposing rooms than any imported marble.

The boards making up the ceiling came from the Celotex Company, a Chicago-based company that had been turning the refuse of sugar production into fiberboard in Marrero since 1921. As one of the first companies to produce insulating boards for construction, it would grow into a global behemoth before succumbing to lawsuits and filing for bankruptcy decades later.

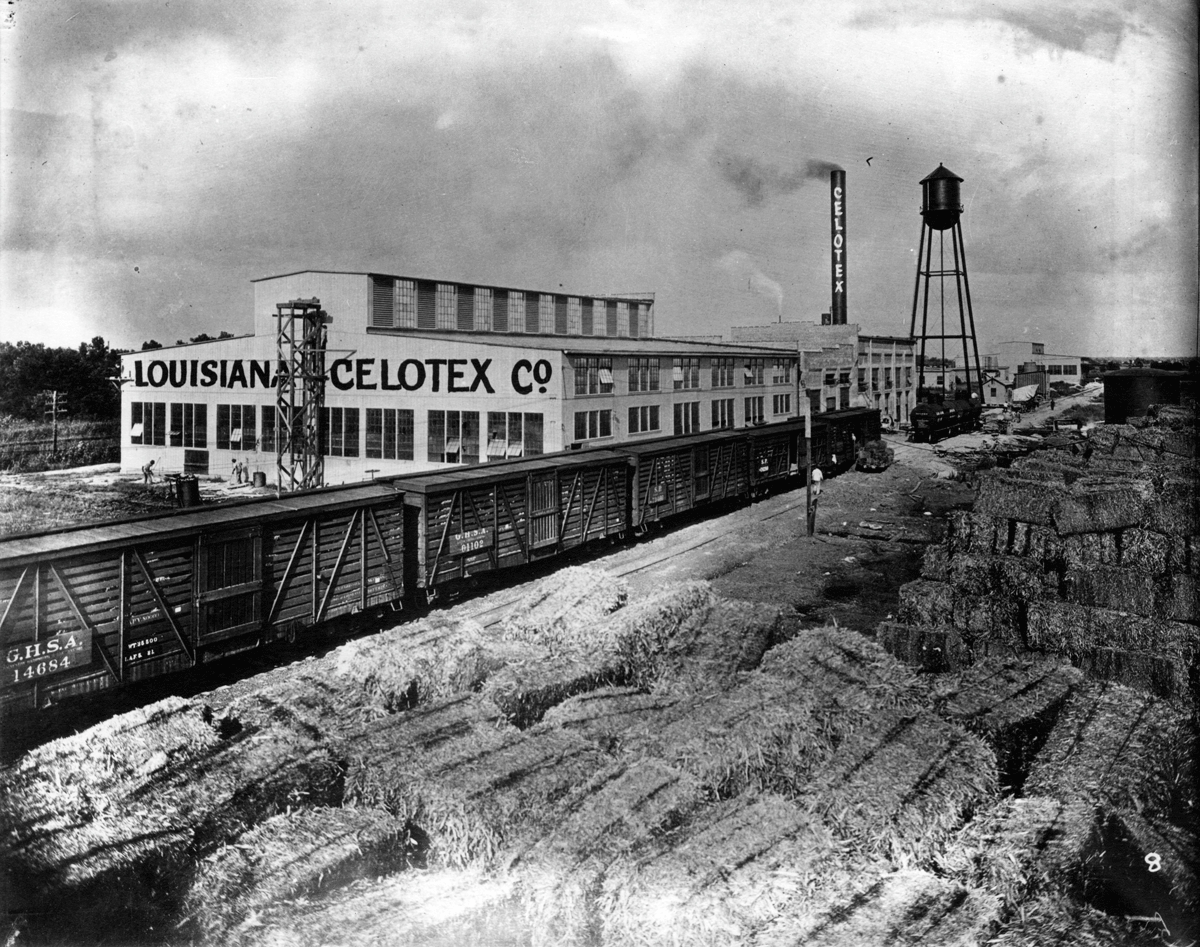

The Louisiana Celotex Co. in Marrero, Louisiana, in 1939. Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection

That demise of the Marrero plant—after years of Celotex buying subsidiary companies before itself being purchased—wouldn’t come until 2009. When the State Capitol was built in 1932, under the direction of Governor Huey P. Long, Celotex was a fresh and shining example of American—and Louisianan—ingenuity. The company “saved the sugar-cane industry in Louisiana from extinction and will eventually affect the entire sugar world,” opined an enthusiastic 1930 article in the journal Industrial and Engineering Chemistry. I imagine the populist governor relished the use of this relatively new product in the State Capitol construction. Maybe he enjoyed the juxtaposition of crowning exquisite marbles from around the world with homegrown handiwork. Or perhaps Celotex was just the best option around.

“It was used because of acoustics,” a guide at the Louisiana State Capitol told me. Indeed, looking closely at the ceilings, I saw a pattern of circular depressions, little pockets of extra sound absorption. They likely used a board designed specifically for that purpose called Acousti-Celotex.

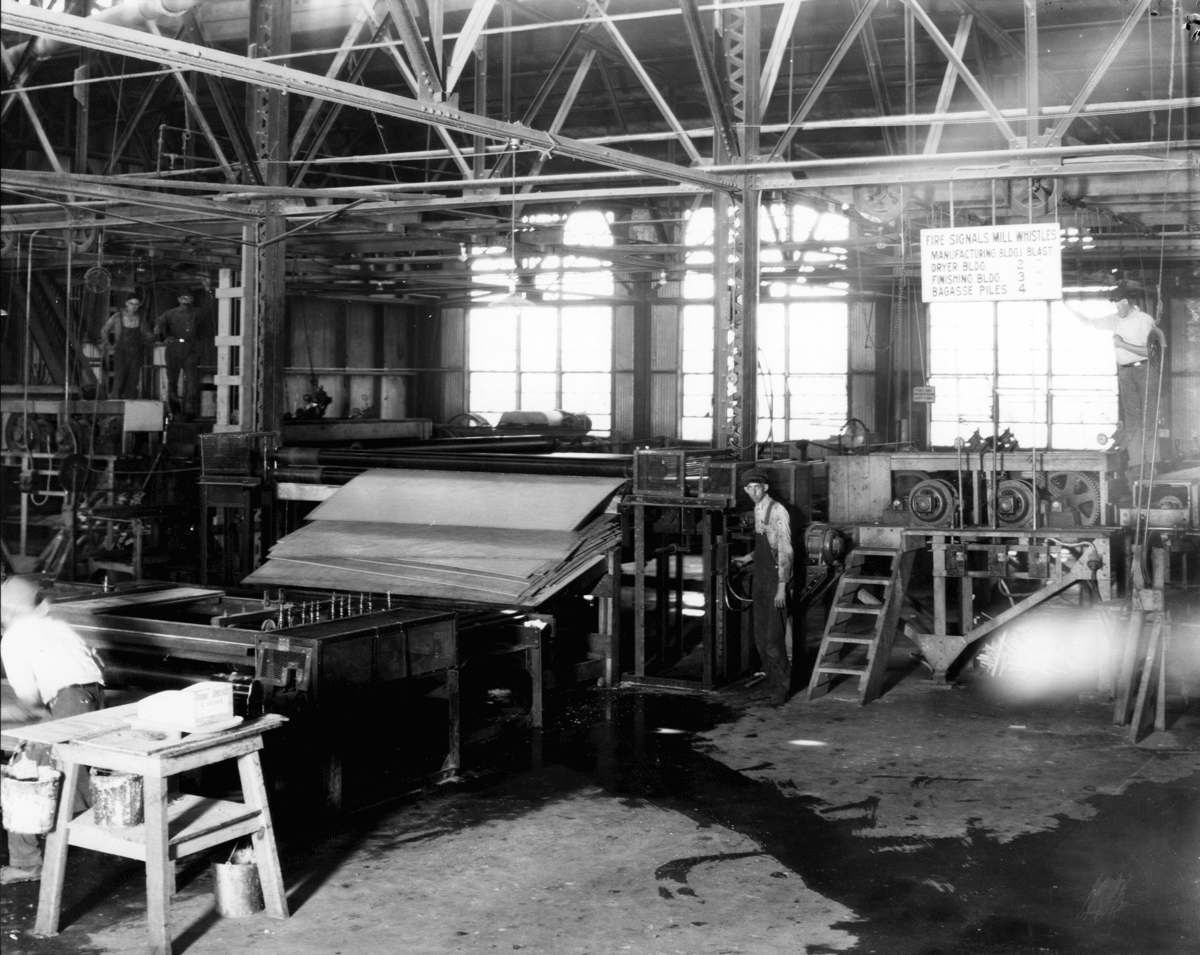

Celotex board products were formed from bagasse, the fibrous material that remains after sugarcane is squeezed between rollers to extract its sugary juices. Before this innovative new use, bagasse had been a bother to growers. It either piled up in fields, leaving less acreage for growing sugarcane, or burned in furnaces to produce steam to run sugar mills. But according to the same Industrial and Engineering Chemistry article, it was “an indifferent, inconvenient, and inefficient fuel, owing to its moisture content, bulk, and low caloric value.”

Bagasse may not burn well, but it makes a strong fiberboard. Under a microscope, cane fibers show saw-toothed edges that cling together with remarkable tenacity. The fibers also hold sealed air pockets, making it a great insulator. Celotex collected bagasse from numerous sugar mills around Louisiana and shipped bales of the stuff to the Marrero plant by rail. There, bagasse was washed, sterilized, and shredded, then fed onto molded rolls, matted together in a felt, and dried in ovens that were eight hundred feet long. The resulting boards were strong and weather resistant, becoming a sought-after building material. Celotex fed the construction industry not only in Louisiana but around the world. At the Marrero plant of the 1930s, 1,300 employees were turning out two million square feet of board a day. Celotex had turned problematic refuse into an economic engine.

Decorative hexagons made from “Acousti-Celotex” make up the ceiling of the Senate Chamber at the Louisiana State Capitol in Baton Rouge. Lucie Monk Carter

Before I left the tour guide at the capitol, she had a tidbit about the ceiling in the Senate Chamber she wanted to share. She circled a little piece of wood stuck into the decorated Celotex with her laser pointer. From our vantage point, it looked like a pencil. In fact, it is a remaining shard from a 1970 bombing of the chamber, enacted on a Sunday morning when the room was empty. “The story goes that it was union men who wanted to get attention for a right-to-work bill they wanted passed. Instead, they got jail time.”

It was a sharp reminder that sometimes plans go awry.

In the case of Celotex, the eventual unraveling had its seeds in its beginnings. In 1921, flush with its success, Celotex bought an asbestos mine in Canada as a subsidiary. Like other makers of building products, Celotex used asbestos fibers for its fire retardant qualities. In the 1960s scientists began warning of the health dangers of asbestos. Lawsuits from sick employees followed. By 1990, facing nearly four hundred thousand lawsuits, Celotex sunk into bankruptcy protection. It emerged from Chapter 11 in 1996 and created the Celotex Asbestos Settlement Trust, funded with $1.5 billion. By 2001 only one hundred workers remained at the Marrero plant. Damage from Hurricane Katrina and a downturn in the national housing market finally did it in. The plant closed in 2009.

Across from the old site on Marrero’s Fourth Street, a Spanish-language Pentecostal church, an air conditioner company, and other small industrial shops form a mile-long row of weathered buildings. Most are made of rusting corrugated metal. Among the few exceptions is a small, squat building of cement blocks that’s home to Prime Time Lounge. The bar is a beloved place to grab a beer and enjoy the jukebox with friends, with the Google reviews to prove it, but its name rings of irony. To the outside eye, the neighborhood looks well past its prime.

The interior of the Louisiana Celotex Co. in Marrero in 1939. Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection

The Celotex plant, with more than 350,000 square feet of buildings on sixty-seven acres, lies fallow. Its own buildings of corrugated metal are rustier than its neighbors across the street. The 1920s-era art deco administrative building burned in 2017, along with its antique furniture and filing cabinets filled with company records. The former bustling plant, the engine of employment and withering illnesses, now appears like an industrial ghost town.

“I’ve seen coyotes roaming around here,” said a resident who lives in the last house on a dead-end street overlooking the old plant. Celotex employed her grandmother for years in an office job. The resident herself worked there for a few days until she quit. She didn’t like the night shift—neither the hours nor her co-workers, mostly men. “Someone lost a little dog; I didn’t want to tell them it was probably one of those coyotes that got him.”

“They make movies there every once in a while,” she added. “At least someone comes to mow the grass from time to time now.”

Film production companies have intermittently expressed interest in renovating the buildings into production facilities. Most recently, new developers bought the plant in July 2023 with plans to lease it out as a production space and filming location.

So perhaps the old Celotex plant will soon enter a second prime.

Kerri Westenberg, a New Orleans writer, was the travel editor at the Star Tribune in Minneapolis for many years. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, Real Simple, Bon Appetit, and other magazines.