Colonial Hubris

Louisiana, Carolana, and the imperial chess match of 1699

Published: February 29, 2024

Last Updated: June 1, 2024

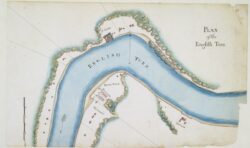

Map by Barthélémy Lafon, The Historic New Orleans Collection

An 1813 diagram of English Turn.

Born in London in 1640, Daniel Coxe studied medicine at Cambridge and became a leading doctor to the royal family. That position gave him the chance to invest in colonial opportunities on the Eastern Seaboard—not by sailing to its shores, which he never did, but by purchasing a patent (land grant) stretching, at least on paper, clear across the continent.

“Between 1692 and 1698,” writes historian G. D. Scull in an 1883 biographical article, “Dr. Daniel Coxe purchased the patent of the province of Carolana,” extending from “North and South Carolina [across] that part of America which lies between the thirty-first and thirty-sixth [parallels], from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific, with the exception of Saint Augustine and New Mexico.” Coxe’s Carolana patent not only disregarded countless Indigenous territories, but also flouted the understandings held by Spain or France that the Mississippi Valley fell within their domain, thanks to either De Soto or La Salle.

Coxe was not ignorant of this colonial competition; on the contrary, he was motivated by it. Just as La Salle’s 1682 claim of Louisiana had provoked Spanish authorities in Mexico to try repeatedly to retake the Mississippi River in the 1690s (all of which were unsuccessful), it spurred Coxe to outdo both rivals with preemptive settlements under the English flag. He did so by funding a number of exploratory forays out of Charleston and sending them into the interior—that is, into Carolana. Or was it Louisiana? Or Nueva España?

Across the Atlantic, officials in France and England had been distracted from colonial affairs in their fighting of King William’s War. After hostilities ceased in 1697, France refocused on La Salle’s Louisiana claim of fifteen years prior, and soon caught wind of Coxe’s provocations. It would later come to light that Coxe planned to send two ships up the “Meschacebe,” as Coxe spelled the Mississippi River, “well armed and provisioned . . . for building a fortification and settling a colony.” One ship would be captained by William Lewis Bond (sometimes spelled Louis Banc, Banks, or Barr), and the other possibly by a man named Metcalf.In late 1697, the French naval minister charged thirty-six-year-old French Canadian warrior Pierre Le Moyne, sieur d’Iberville, to seek the mouth of the Mississippi River, and as quoted by historian Tennant S. McWilliams, “select a good site that can be defended with a few men, and block entry to the river by other nations.” Iberville had gained fame for his heroic exploits against the English in French Canada; in fact, he had once personally captured Bond in an engagement on the Hudson Bay, and later released him.

Along with his younger brother Jean Baptiste Le Moyne, sieur de Bienville, Iberville departed France with a crew in late 1698, and sailed up the Mississippi in March 1699. They soon convinced themselves that this was indeed La Salle’s Louisiana claim from seventeen years earlier. Iberville’s mission was to establish a presence in the region on behalf of his monarch—which fairly well describes the aim of his rivals, namely Coxe and his Carolana cronies, as well as the Spanish, who were sending reinforcements to their Florida colony. Writes historian Charles Nathan Elliott in his 1997 thesis, “the French presence [in Louisiana] and Spanish presence at Pensacola were all due to Dr. Coxe reviving the colonial aspirations and fears created by La Salle’s . . . claim . . . for France.” One can imagine our region in the late 1690s as a high-stakes chess game, with French, Spanish, English, and Indigenous stakeholders all around the board, but nobody completely confident they understood who was actually playing what, where, and when.

One day in the late summer of 1699, while Iberville explored elsewhere with most of the expedition, young Bienville and five crewmembers sailed two longboats on the Mississippi roughly twenty-five leagues (seventy-five river miles) up from the mouth, in today’s upper Plaquemines Parish. At a sharp meander where winds reversed directions, the Frenchmen came upon an enemy chess piece, and a powerful one at that: a “corvette of ten guns,” according to Iberville’s description of what Bienville later told him, “at anchor, awaiting favorable winds to go farther upstream.” By other accounts, the warship was a larger frigate or a two-mast brigantine. It flew the English flag, bore the name Carolina Galley—Coxe’s patent, spelled the alternative way—and was captained by none other than William Lewis Bond.

But as any chess player knows, a well-positioned pawn can take a knight. Or a king.

Along with the second vessel, possibly captained by Metcalf but not present at the encounter, Bond’s vessel carried “thirty French or English gentlemen volunteers,” writes the historian Scull, citing Coxe’s records, “besides sailors and other men of lower rank.” Those French volunteers were Huguenots, French Calvinists, who had been persecuted in France and some of whom sought refuge in the English colonies. Captain Bond understood Carolana—that is, Louisiana—to be an English colony, and he intended to establish an English settlement here. Only one chess piece stood in Bond’s way, and it was hardly intimidating: five French sailors, two wobbly longboats, and one nineteen-year-old named Bienville.

But as any chess player knows, a well-positioned pawn can take a knight. Or a king.

Bienville sent two of his men to row over to the Carolina Galley and demand Bond “to immediately leave the country,” being a French possession, “and that, if he did not leave, he would force him to.”

What force? Everything Bienville could bring to bear was in those two longboats. The only thing that made his threat credible was the fact that Bond had recognized Bienville as the brother of the feared Iberville, all three of whom had been at that Hudson Bay battle. And now here they met again, in a freak encounter 1,600 miles to the south.

As Bond mulled his options, he bought time by questioning Bienville about English activity upriver, a reference to that other Coxe-funded ship, possibly that of Metcalf. Bienville played coy, sowing doubt that he and Bond were even on the Mississippi, while asserting adamantly they were in French Louisiana. Bond started to buckle, justifying his own legitimacy by recounting details one ought not disclose to an enemy. The English expedition originated, Bond revealed to Bienville, during the prior year, when rumors circulated that Iberville’s expedition to Louisiana had been forced to return to France. That gave Bond an opportunity to organize his expedition of three ships, which departed London in October 1698 for Charleston, bound ultimately for the Mississippi River. One ship returned, while the other two, armed with “twenty-six twelve-pounder [guns], set out again from Carolina in May 1699,” wrote Iberville of what his brother had heard from Bond, “looking for the Mississippi.” Bond entered the river on August 29—and ran smack into Bienville on September 15. (Dates vary in accounts written by other colonists.)

Bienville exchanged words with Bond not once but thrice that September day, probably using the crew to row the messages back and forth. All the while, Bienville’s stature grew—think of a pawn promotion in chess—while Bond’s diminished. The English captain seemed to over-explain himself, ingratiating to the lordly youth and even bargaining down his own position. According to Iberville’s recount, Bond said he would “come back and settle this river with ships having bottoms better constructed for the purpose,” after which perhaps English and French interests might split the territory, one on each bank, since Bond felt “it was as much theirs as ours.”

Captain Bond then turned around the Carolina Galley and sailed back to Charleston. Bienville’s bluff won the chess game for the French, and they could now proceed with establishing Louisiana. Frenchmen dubbed that prominent riverbend where the encounter took place le Detour aux Anglois, and we call it English Turn to this day. Though Bond never returned to Louisiana, his 1699 foray motivated the French to expect future incursions. In 1700 Iberville built a blockhouse to defend the river in what is now Phoenix in Plaquemines Parish, while in 1718, Bienville selected a riverfront perch for New Orleans in part for its defensive position, and later had two forts erected at English Turn.

And what of Carolana? Bienville’s bluff had truncated Coxe’s coast-to-coast patent to where it intersected the Mississippi Valley. Lands to the west would be French domain, while lands to the east would be British. Today, the northern border of North Carolina runs roughly along the 36th parallel, while parts of Louisiana’s, Alabama’s, and Florida’s borders trace the 31st parallel, all of which are artifacts of Coxe’s Carolana patent.

Dr. Daniel Coxe lived to see this geopolitical chess game play out, and recounted the exploits in a 1722 treatise drawn from various reports and journals. In his “Description of the English Province of Carolana, by the Spaniards Call’d Florida and by the French, La Louisiane,” Coxe wrote that in 1698, he had “equipp’d and fitted out Two ships, [with] Twenty great Guns, Sixteen Patereroes [swivel guns], Small Arms, Ammunition [and] Provisions,” manned with “Sailors and Common Men, [plus] Thirty English and French Volunteers,” that last reference meaning the Huguenots. “One of the Vessels,” he continued, “discover’d the Mouths of the great and famous Mefchacebe [Mississippi], enter’d and ascended it above One Hundred Miles,” putting it near future New Orleans. Coxe then wrote that one captain “had perfected a Settlement therein, if the Captain of the other Ship had done his Duty and not deserted them,” implying that a scandalous retreat—presumably by Bond at English Turn—had ruined the whole effort. All those on the other ship could do to take “Possession of this Country in the King’s Name,” wrote Coxe, was to leave “in several Places, the Arms of Great-Britain affix’d on Boards and Trees.”

Checkmate.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Draining New Orleans, The West Bank of Greater New Orleans—A Historical Geography, Bienville’s Dilemma, and other books. He may be reached at [email protected], richcampanella.com, or @nolacampanella on X.