Winter 2025

The Decadent Double Dealer

New Orleans’s national literary magazine of the 1920s

Published: December 1, 2025

Last Updated: December 1, 2025

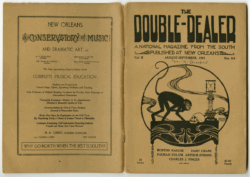

Courtesy of HNOC

The Double Dealer, August-September 1921 cover and back cover. Leonhardt, Olive (cover artist).

In 1921, four ambitious young writers living in New Orleans—Julius Weis Friend, Basil Thompson, Albert Goldstein, and John McClure—seized upon the idea to begin publishing their own literary magazine. Out of 204 Baronne Street, they began the forty-two-issue run of The Double Dealer. The magazine is often viewed as part of literary modernism due to its publication of early work by writers who would go on to become Modernist superstars, including William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway. But the scholarly focus on the magazine’s connections to modernism obscures another vital literary movement that the Double Dealer helped to revitalize: decadence.

Emerging in the late nineteenth century, decadence embraced indulgence, experimentation, languor, and a rejection of conservative nineteenth-century mores. Through social and cultural transvaluation, the “ugly,” “sinful,” and “diseased” was rendered as beautiful. This avant-garde movement attracted poets, essayists, short story writers, drinkers, opium users, queer men and women, aesthetes, classicists, Francophiles, “New Women,” socialists, Catholics, and others who lived against the grain of social norms. In their writing and art, they played across languages, forms, and the senses to push the boundaries of genre and what counted as art. Sometimes the result was grotesquely self-indulgent, focused on the individual’s hedonistic experience and egotistic self-aggrandizement. Sometimes the result was politically progressive, anti-industrial and anti-capitalist, and challenging to the heteronormative status quo.

Most histories of the movement begin with French poets, like Charles Baudelaire and Paul Verlaine, and prose writers, like Guy de Maupassant and Joris-Karl Huysmans. These writers turned an aesthetic eye on, among other things, decomposing bodies, the cracking makeup of can-can dancers, and the exotic monstrosity of the hothouse plant.

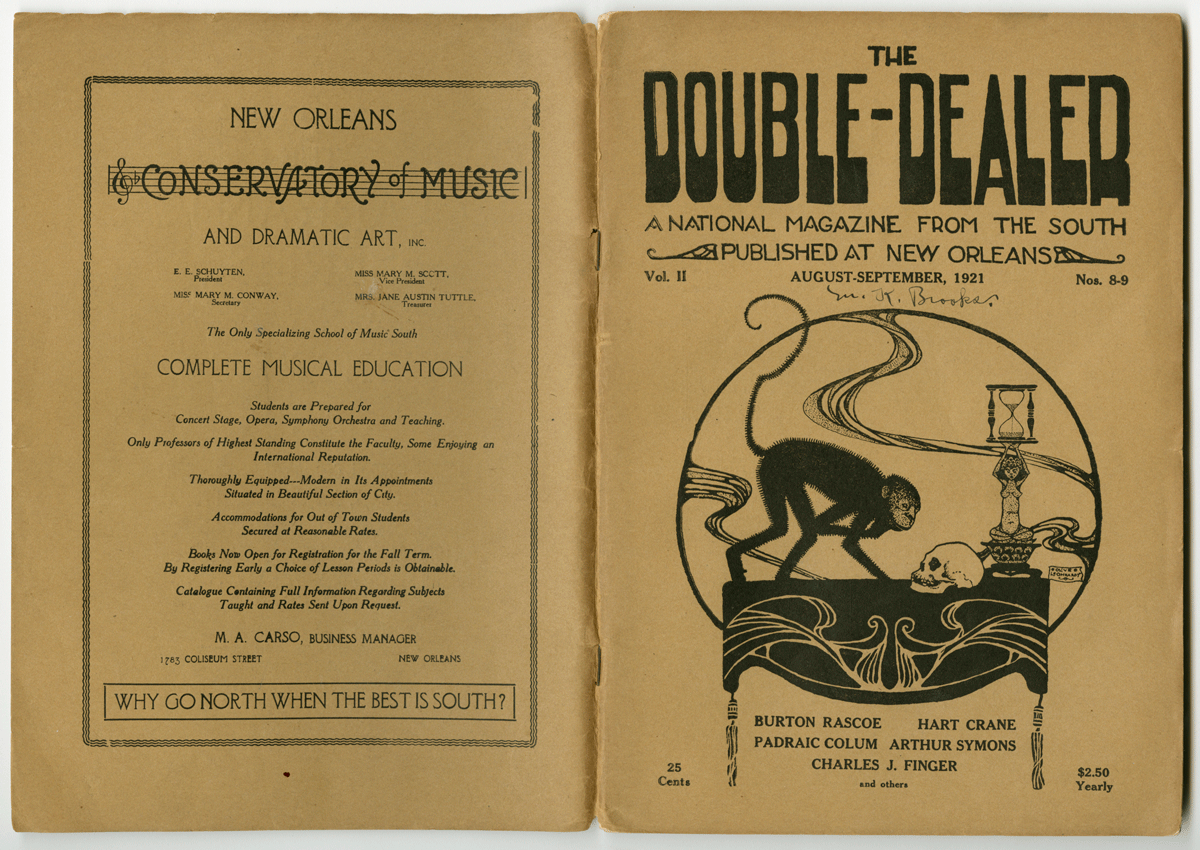

Courtesy of HNOC

British decadence splashed in its own playful humor and “aestheticism.” Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde argued for “art for art’s sake,” Arthur Symons and Ernest Dowson wrote rich and elaborate poetry, and Max Beerbohm and Hubert Crackanthorpe wrote tongue-in-cheek essays about the superiority of artifice over nature. The Decadent movement drove an influx of “little magazines,” literary periodicals including The Savoy, The Chameleon, and, most famously, The Yellow Book. With their editorial choices and their design—particularly the artistic stylings of Aubrey Beardsley—these periodicals helped set the tone for the British movement, establishing conventions that The Double Dealer would later embrace.

The magazine [published] early work by writers who would go on to become Modernist superstars, including William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway.

In the United States, the initial thrust of decadence didn’t capture quite as much attention, though a smattering of aecrtists aligned with the movement, including writers associated with Louisiana such as Kate Chopin and Lafcadio Hearn. However, American decadence saw a 1920s revival. Authors dove back into literary excess, artifice, and strangeness with all of the enthusiasm of the Jazz Age. This came with second flurry of little magazines, including The Little Review, The Dial, and New Orleans’s Double Dealer.

The flowering of literary decadence in New Orleans makes a certain amount of sense. In his book Three Hundred Years of Decadence (LSU Press, 2019), Robert Azzarello paints a vivid picture of New Orleans’s resonance with the aesthetic preoccupations of the decadence movement:

brick buildings crumbling into red dust, houses half-eaten by termites and cat’s claw, water rising from the ground, wooden frames rotting from the inside out, mold growing and paint chipping away. […] Then there is the litany of vices: prostitution and miscegenation, homosexuality and gender deviance, and more than one of the seven deadly sins. Add to this list the city’s stubborn Francophilia, its Afro-Caribbean connection, its Catholicism, its air of mystery and detection, its preoccupations with the dead and the undead, its seemingly perpetual state of human violence, and a strange pattern starts to emerge.

Many of the signature characteristics of New Orleans—its mix of French, Spanish, and Afro-Caribbean cultural influences; its permissiveness and freedom; and its environmental precarity—have historically been and continue to be both praised and criticized as “decadent.” It is no coincidence that New Orleans’s biggest celebration of LGBTQ life is called “Southern Decadence.”

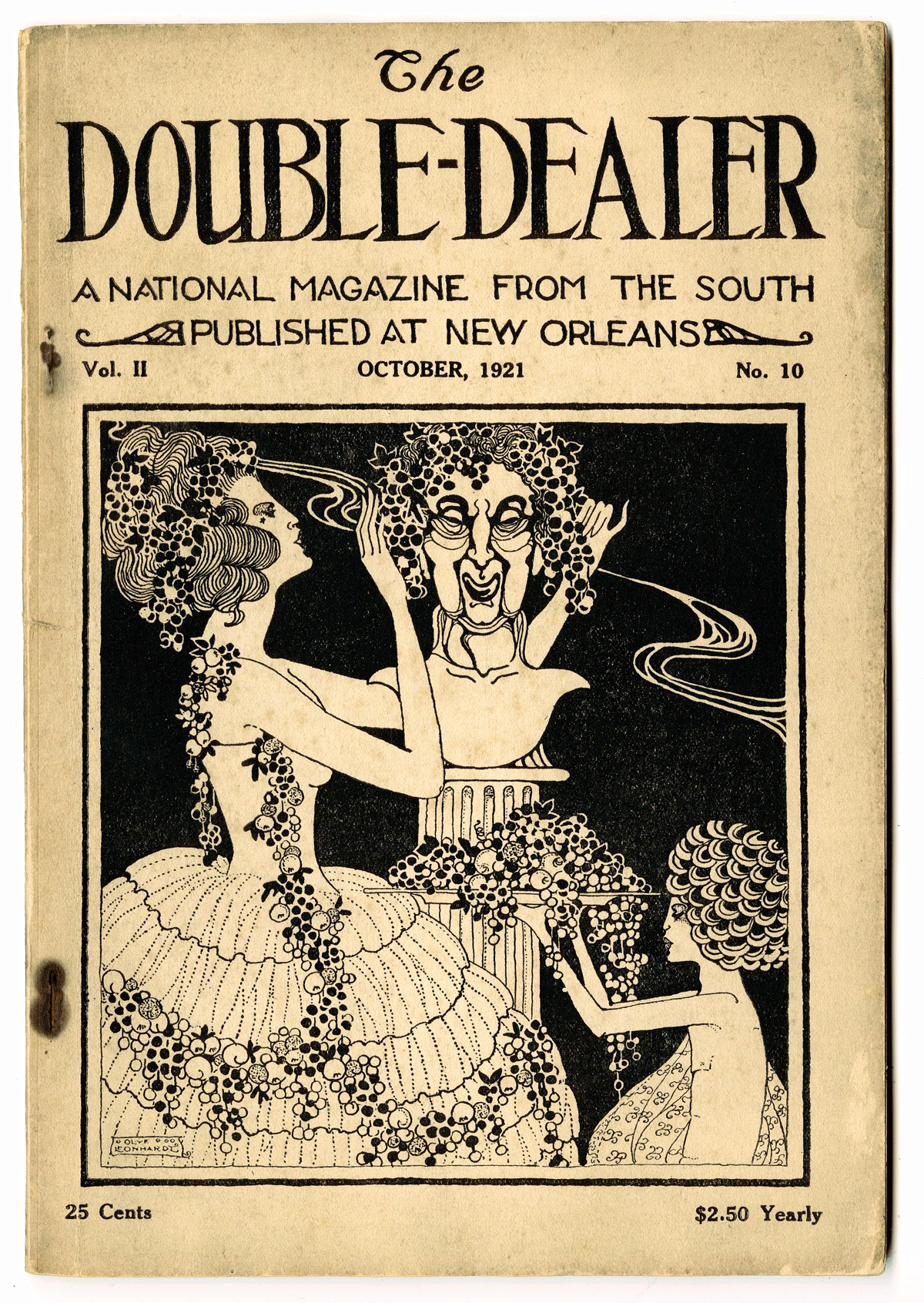

The Double Dealer, July 1921 cover. Courtesy of HNOC

These features were a major draw for the coterie of 1920s New Orleans artists that scholar John Shelton Reed has called the “Dixie Bohemians.” Aspiring authors and aesthetes in New Orleans’s French Quarter developed intellectual salons, an art school, an architectural restoration firm, childish antics, and a literary magazine. The Double Dealer was founded in rent-free digs furnished, according to Julius Weis Friend, with “overstuffed chairs and lounge, pictures, easels, dueling pistols, and two human skulls.” The magazine declared its intentions with its title and motto “I can deceive them both by speaking the truth,” an ironic bon mot in the style of Oscar Wilde. The founders also set out, within the first few issues, to make a splash beyond Louisiana. They added the subtitle “A National Magazine from the South” and recruited correspondents from Chicago, New York, and Paris.

In a 1978 essay published posthumously in The Mississippi Quarterly, Friend describes the early days of The Double Dealer as seeped in “an inordinate love of the English authors of the 1890s.” In work they published in The Double Dealer, the editors continuously discussed Decadent authors like Huysmans (referenced in seven different essays), Baudelaire (eighteen essays), Dowson (ten essays), Symons (seven essays), and Hearn (three essays). They also reprinted Dowson’s poems and Hearn’s short stories and essays with regularity. Most notably, Symons acted as a foreign correspondent for the magazine from July 1921 to November of 1923; writing from Paris, he contributed regularly to the magazine, publishing six poems and twelve essays.

The visual similarities between the early issues of The Double Dealer and the designs of The Yellow Book and The Savoy are striking. The artwork of Olive Leonhardt, obviously inspired by Beardsley, offers swathes of inky black contrasting with tiny textural details. These art pieces are laid against solid-colored yellow covers in a similar shade as The Yellow Book and blues and reds similar to issues of The Savoy. Julius Weis Friend notes the similarity in his 1978 essay, describing Leonhardt’s style as “nymphs and satyrs aplenty done in the Beardsley manner.” Her choices of subjects and themes are clearly inspired by decadence as well, with supernatural figures, nudity, Pierrots, irreverently rendered religious iconography, classical statuary, and femmes fatales.

The significance of The Double Dealer as a Decadent revival publication is bound up in the events that led to the original movement’s fall in the late 1890s. In 1895, Oscar Wilde was convicted of “gross indecency” for his sexual relationships with men and sentenced to two years of hard labor. When Wilde was arrested, he was holding a “yellow book” that linked the Wilde trials with the literary magazine of that name in the public imagination. Wilde was marked publicly as a “sexual deviant”; everything associated with him also came under reactionary fire. Queer writers fled to France, The Yellow Book fired its editor and artist most associated with decadence (Arthur Symons and Aubrey Beardsley, respectively), and many authors and works which had recently been described as part of the decadence movement were suddenly rebranded—as Symbolism, Impressionism, Aestheticism, or some other related but less fraught descriptor. Decadence came to be nearly synonymous with homosexuality. It was a movement that was shunted aside, essentially, for being too queer.

The editors of The Double Dealer didn’t fear association with Wilde or “sexual deviance,” and, instead, engaged in a project of revitalization for a maligned movement. Rather than distancing itself from queer authors, the magazine made LGBTQ authors part of the fabric of the publication. The Double Dealer emerged from the New Orleans’s 1920s bohemian community, significantly shaped by the participation and patronage of gay and bisexual artists and scholars—including William Spratling, Weeks Hall, Samuel Louis Gilmore Jr., and Lyle Saxon. The most important queer contributor to the magazine was Gilmore, who, as John Shelton Reed put it in Dixie Bohemia (LSU Press, 2014), “serv[ed] in various capacities including associate editor, and contribut[ed] poetry, short plays, stories, book reviews, and money.” During The Double Dealer’s run, Gilmore published eighteen poems, six one-act plays, and fifteen book reviews.

In his introduction to Decadence: A Literary History (Cambridge University Press, 2020), Alex Murray suggests that decadence is “a means of articulating, at moments of crisis and change, the need to live beautifully, queerly, excessively.” It’s an apt description of the ethos of New Orleans—and perhaps explains why decadence has resonated so powerfully in this city for at least a hundred years.

Katie Nunnery completed her PhD In English at the University of Connecticut in 2020 and currently teaches literature and composition at LSU – Shreveport.