Battle of Lake Pontchartrain

The Battle of Lake Pontchartrain took place during the American Revolutionary War and ended British control of inland lakes and waterways near Spanish New Orleans.

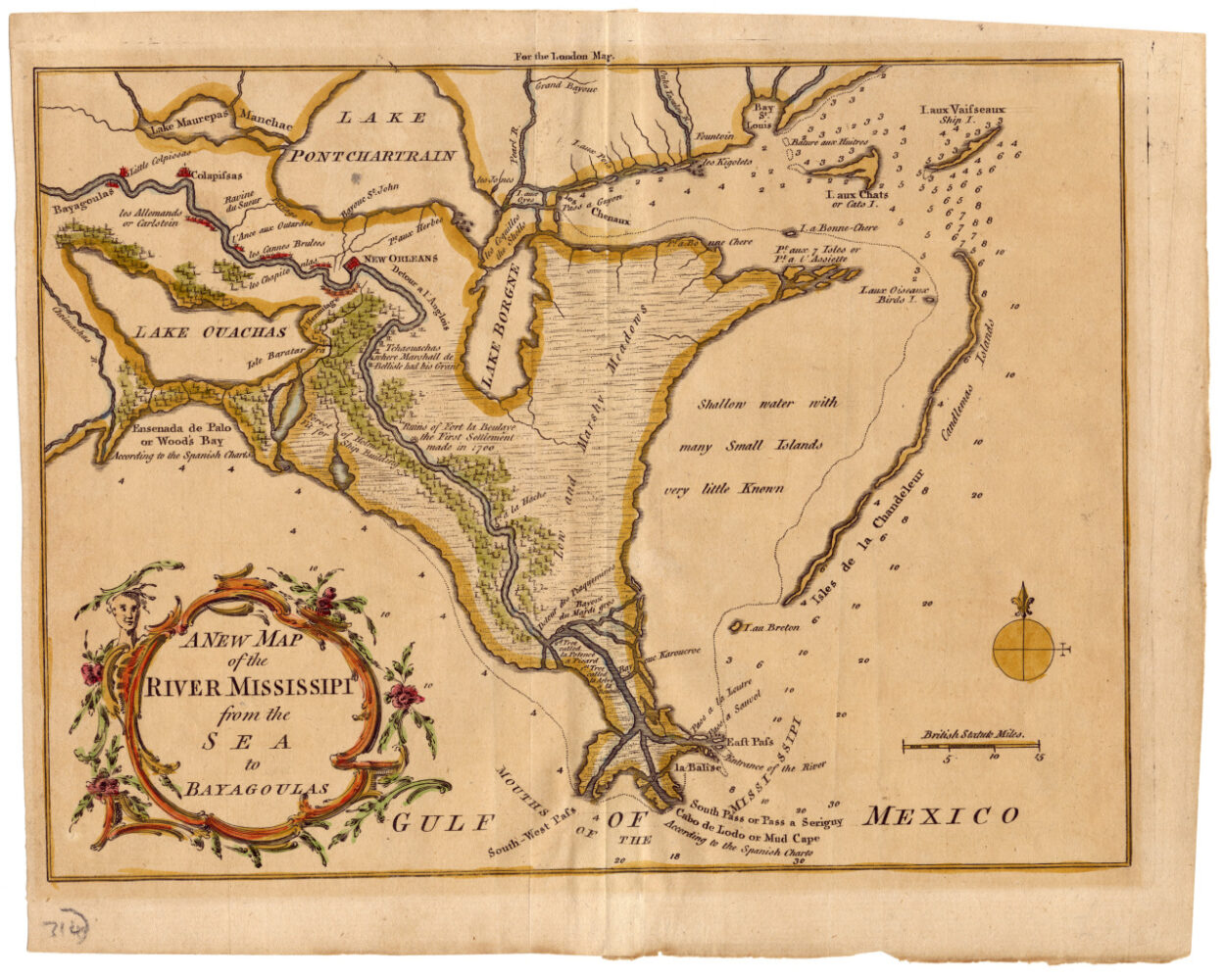

The Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of Mrs. Henry C. Pitot, Acc. No. 1993.2.20.

A 1759–1764 map of the inland waterways of West Florida where tensions grew between the Spanish and British officials during the American Revolutionary War.

The Battle of Lake Pontchartrain on September 10, 1779, was a naval fight during the American Revolutionary War between the British Royal Navy’s sloop-of-war West Florida and an American privateer schooner. The battle resulted in the capture of the British vessel and ended British control of the inland lakes and waterways near Spanish New Orleans.

Background

Prior to Spain’s declaration of war on Great Britain in June 1779, the Spanish colonial governor of Louisiana, Bernardo de Gálvez, quietly supported Continental forces by sending them money and military supplies, often in consultation with Oliver Pollock, a prominent Irish-born merchant in New Orleans who also served as a commercial agent for the Continental Congress. Gálvez’s secret support of the American cause was a continuation of the policy established by his predecessor, Luis Unzaga.

After the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, tensions slowly grew between the Spanish government in Louisiana and British officials in West Florida, the colonial province that extended from the Mississippi River to the Apalachicola River east of Pensacola, the provincial capital. Spanish Louisiana and British West Florida were separated by a long border of inland waterways consisting of Lakes Borgne, Pontchartrain, and Maurepas, as well as Bayou Manchac and the Amite River. British officials in Pensacola were aware that the westernmost parts of West Florida bordering the Mississippi River were vulnerable to attack and that naval control of the inland waterways was needed to maintain communication between Pensacola and the British posts on the Mississippi.

The armed Royal Navy sloop West Florida had been patrolling the lakes since the summer of 1776. Commanded by Lieutenant John Burdon, the West Florida targeted Spanish smugglers and confiscated small vessels and contraband goods. Burdon occasionally added insult to injury by sailing close to the Spanish Fort at Bayou St. John while flying the Union Jack. Burden and his men became even more active during 1778, in response to an American expedition to British West Florida led by James Willing. Though unable to find Willing on the Mississippi River, Burdon continued to assert the Royal Navy’s dominance of the inland lakes and Mississippi Sound.

After two years of active service and showing signs of wear, the West Florida returned to Pensacola for repairs and Burdon was replaced by a new commander, Lieutenant John Payne, who took the West Florida back to sea in February of 1779. The ship returned to the lakes bordering Spanish Louisiana by summer, just as Spain declared war on Great Britain and Gálvez began his campaign to capture the British forts on the Mississippi River. Payne did not know that his country was at war with Spain. Gálvez and Pollock had set their sights on the West Florida, knowing that its destruction or capture was necessary to break the Royal Navy’s control of the lakes and to cut off the British forts on the Mississippi from further communication, resupply, or reinforcement from Pensacola.

To this end, Pollock outfitted a vessel, formerly known as the Rebecca, as an American privateer with a crew and armaments and named it the Morris in honor of his friend Robert Morris of the Continental Congress, placing it under the command of Philadelphia native William Pickles. Unfortunately the Morris was soon lost in the hurricane that battered New Orleans and nearly ended Gálvez’s planned campaign, but a replacement was soon raised from the river, a small schooner that could carry cannons and sufficient crew to replace the Morris as a privateer. Pickles left New Orleans in late August with a Spanish and American crew of fifty-eight men to seek out the West Florida on Lake Pontchartrain.

The Battle

On the afternoon of September 10, 1779, the West Florida came alongside a small schooner sailing under a British flag. Lieutenant Payne called out to the vessel and was told she was a merchant carrying supplies to Manchac. However, Payne and his crew of about twenty-eight men were surprised when the schooner’s larger crew quickly hauled down her British flag and raised an American flag before firing muskets and throwing grappling lines to pull the two vessels together. The British sailors were unprepared for the attack, having removed the anti-boarding barricades from their deck the previous day. Though exposed to musket fire, they successfully prevented at least one boarding attempt before being overwhelmed. It was a brief battle of twenty minutes that Pickles described as “very violent.” The American privateer schooner lost eight men and had some additional wounded. The West Florida had four killed, including Payne, and the rest were taken prisoner. The American victory was all the more surprising in light of the West Florida’s superior firepower, though neither vessel fired its cannons. Pickles took the captured West Florida into Bayou St. John.

Aftermath

With the capture of the West Florida, British control of the waterways above New Orleans ended, and Spanish sailors were able to seize additional British vessels carrying supplies to western outposts. On October 16, 1779, Pickles sailed the armed American schooner to the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain and received the surrender of British subjects living between Bayou Lacombe and the Tangipahoa River.