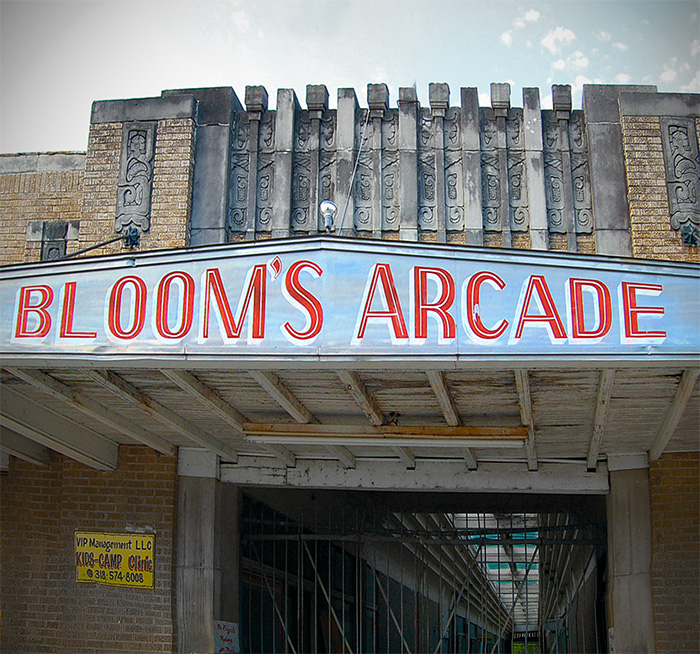

Bloom’s Arcade

Bloom's Arcade, one of Louisiana's first shopping centers, was built in Tallulah in 1930 and served as a centerpiece of the Madison Parish town’s business district for half a century.

Courtesy of Jennifer Baughn.

Bloom's Arcade in Tallulah is Louisiana's only surviving example of the shopping arcade, the precursor of the shopping mall.

Bloom’s Arcade, one of Louisiana’s first shopping centers, was built in Tallulah in 1930 and served as a centerpiece of the Madison Parish town’s business district for half a century. In an era dominated by stand-alone stores, the arcade featured a movie theater, a gas station, and sixteen other businesses under one roof. It also provided ample parking at a time when automobiles were just beginning to attain widespread popularity among residents of rural northeastern Louisiana. Its fortunes have fallen in recent years, but the significance of its architectural and commercial innovations has not diminished.

When Mertie Bloom’s new shopping arcade began to rise in downtown Tallulah at the onset of the Great Depression, he was optimistic about the future of his unusual retail venture. It was well positioned, adjacent to the railroad depot and immediately visible to disembarking passengers. The building’s other side faced US Highway 80, the main east–west route across northern Louisiana. To encourage motorists to stop, Bloom incorporated a filling station on the building’s corner. An additional attraction was a movie theater, which occupied the building’s downtown end.

Bloom blended old and new retail concepts in his shopping complex. He included a covered pedestrian arcade to protect shoppers from rain and heat; although this feature was a proven success elsewhere, it was new to Louisiana. Also new to the state was the combination of different services and entertainment in one building. Significantly, Bloom had located his building in a spot that offered plenty of parking, which was becoming an essential component of retail planning. Yet, despite these features and location, Bloom needed to give his building an arresting architectural presence on the street to entice shoppers into the covered arcade. For that, he turned to architect N. W. Overstreet of Jackson, Mississippi.

Forerunner to the Modern Shopping Mall

Overstreet produced a design that was as modern as Bloom was forward-thinking. The long, single-story concrete building is faced with a buff-colored brick. Although some of the shops had windows facing the street, the interior shops that ran through the center of the building needed an eye-catching portal to act as a “billboard” to draw customers inside. Overstreet embellished the entrances at each end of the arcade with a bold, ornamental front composed of vertical piers, alternately narrow and wide, that extend beyond the roofline to create a dynamic crown. Recessed panels between the piers are adorned with art deco designs featuring stylized floral and intertwining motifs made of cast stone (a fine-surfaced concrete). The wide piers that bookend this design include vertical panels densely filled with serpentine forms that ensnare rosettes and acanthus leaves. All of this decoration is in shallow relief with a decided linear emphasis that seems almost soft and malleable, and contrasts nicely with the smooth, crisp brick. A canopy runs the entire length of the building on its railroad-facing side and, as it reaches the arcade entrance, the canopy extends into the shape of a shallow pediment. “Bloom’s Arcade” is spelled out in large letters along its edge.

The arcade, three hundred feet long and eighteen feet wide, is illuminated by a full-length skylight of translucent glass supported on steel trusses. Brick piers with capitals ornamented with stylized rosettes and volutes disguise the steel supports. The glass roof is supported on a box cornice that steps back in five stages and runs the entire length of the arcade. The effect is smooth, streamlined, and dynamic. At each end of the arcade, the entrances are highlighted on their inner sides by panels of stylized ornamentation that echoes that of the exterior sculpture. The arcade has a terrazzo floor.

An Array of Shopping and Entertainment

According to reports in the Madison Parish Journal, the arcade opened with eighteen commercial businesses. Only two of them—the theater and the filling station—were accessed from the exterior. Other stores included W. A. Dozier’s jewelry shop, a billiards room, a barber shop, a restaurant, a grocery, and the Max Levy and Company department store, Madison Parish’s oldest and largest department store. Bloom’s Drug store, which also occupied the space, offered such amenities as two soda fountains and a luncheonette, and had fixtures of inlaid walnut.

A vertical sign marked the entrance to Bailey’s movie theater. To show that it was an integral part of Bloom’s building, Overstreet decorated its entrance with ornamental panels similar to those at the arcade’s main entrances. The theater was one in a chain of theaters throughout central and northeastern Louisiana owned by Robert Lee Bailey Sr. of Bunkie. Bloom leased the space to Bailey. The theater seated 680 people and was cooled by a Nu-Air Cooling System.

Johann F. Geist, in his book Arcades: The History of a Building Type (1983), relates that arcades came about in response to the specific need for a public space protected from traffic and weather, and they were a new means of marketing luxury goods. Bloom’s Arcade had an added and modern dimension: it was a retail complex that catered to shoppers arriving by automobile. Its model might have been Kansas City’s Country Club Plaza, built in 1924 and enormously influential in its provisions for “park and shop.” Built to a unified plan and in a single and fashionable architectural style, it helped make the term “shopping center” popular. Country Club was owned and operated by a single entity that leased space to tenants and included a movie theater. Bloom took those successful ingredients to his Tallulah building just a few years later.

While the automobile gave rise to shopping centers and made them successful, it also ultimately destroyed many of them. Small in-town shopping centers like Bloom’s could not compete with the enormous edge-of-town shopping malls or megastores. By the late 1990s only a few of the spaces in Bloom’s Arcade were occupied.

In 1989 Bloom’s Arcade was added to the National Register of Historic Places. In 2011 renovations began on the long-neglected building. With funding provided, in part, by historic rehabilitation tax credits, Bloom’s Arcade was converted into thirty senior-citizen apartments by Brownstone Affordable Housing, Ltd., of Houston, Texas.