Bousillage

Bousillage, a mixture of clay and straw or Spanish moss used for insulation, is a distinguishing feature of Louisiana's architectural past.

Public Domain.

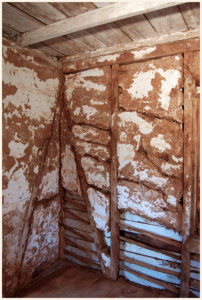

A photograph of a Bousillage wall. Bousillage refers to a mixture of clay and vegetal binder, such as straw or Spanish moss, that forms the exterior walls of wooden buildings.

Bousillage is a type of clay insulation common to the vernacular architecture of Francophone communities in France, Canada, the French Antilles, and the former colonial French outposts in the Mississippi Valley, including Louisiana. In French Louisiana, bousillage refers to a mixture of clay and vegetal binder, such as straw or Spanish moss, that forms the exterior walls of wooden buildings. This earthen composite is also used to seal the gaps between boards of buildings.

The Vocabulary of Bousillage

The term is derived from the French bouse, or cow dung. When used as a transitive verb, bousiller literally translates as “to fill up with dung.” Bousillage in Louisiana, however, is a kind of adobe or wattle and daub composed of locally collected loess soil and clay deposits mixed with a vegetal binder. Binding materials include Spanish moss, straw, animal hair, or other fibrous materials that increase the tensile strength of the application. Some builders occasionally add lime to the mixture.

At the end of the nineteenth century, New Orleans native and local-color writer George Washington Cable recorded in his notes the process that people of Acadian descent used to produce bousillage: “Adobe [was] made by making layers of clay & moss with pit wetting [saturating] with water and everybody men, women & children get in & tramp. Make into rolls 2 feet long & lay over the pins & bend down at ends—smooth by hand & whitewash.” Vernacular Creole architecture, particularly in raised Creole cottages, also utilized this construction technique.

Home builders placed this insulating material by torche entre poteaux. Torche means the amount of bousillage that an individual can hold in two hands; entre poteaux is an architectural design that consists of clissage—a latticework of non-load-bearing wooden batons, or barreaux—which gives the structure form and rigidity while supporting the substantial weight of the bousillage. In Louisiana, barreaux were arranged horizontally between studs and joists, as opposed to vertically as in the European tradition, and they supported walls that were often as much as one foot thick. When bousillage was molded into bricks infilling between studs, Francophones termed the application briquette entre poteaux. This earthen mixture was also used as infill between the cracks of colombage, or timber-frame houses.

Bousillage in Louisiana

In North America, bousillage is a marriage between European and Native American architectural traditions. The technique, which distinguished French colonial architecture from that of New England and New Spain, incorporated indigenous natural ingredients. W. W. Pugh, a prominent Bayou Lafourche sugar planter, recalled of his Louisiana childhood along the bayou that local “architecture had nothing very attractive about it, as the houses were generally small, each provided with front galleries, and walls built of a mixture of moss and bayou sand.” The bousillage walls were exposed to the elements. “At the time whitewash was not in such general use,” Pugh wrote, “and many of the buildings were not even protected from the beating rains by weatherboarding, but they were built from heavy timbers, and the walls were well calculated to keep out the cold of winter and the heat of summer; in fact, they were built with great powers of resistance to the equinoctial storms [hurricanes] which often during that period created greater destruction than those which occasionally visit us during the present time [in the 1880s].”

Throughout the nineteenth century, travel writers consistently commented on the unusual—but highly effective—construction and insulation technique. James Leander Cathcart discussed the construction materials used in St. Martinville at length:

“Some few houses are in part built of brick, but mostly of Mud, & many of the old wealthy inhabitants retain their original shed, with very little improvement to cover them—The houses which are built of Mud … mix’d with moss, with which every tree is nearly cover’d, it is put up by hand, without the use of the trowel, on shelves places [sic] from one frame to the other, & becomes very hard & strong, when thoroughly dry, some plaster over, some white wash … only, & the poorer class leave them in their original state, owing to the Scarcity of lime, their only resource being to bring clam shells from the Lakes, or Oister [sic] shells from the Sea shore to make it.”

Charles Dudley Warner, another nineteenth-century writer, noted during his tour of French Louisiana that a bousillage “house, like all in this region, [stood] upon blocks of wood, [and was] in appearance a frame house, but the walls between timbers [were] of concrete mixed with moss, and the same inside as out. It had no glass in the windows, which were closed with solid shutters. Upon the rough walls were hung sacred pictures and other crudely colored prints.”

Today bousillage is a characteristic feature of Louisiana’s architectural past. In the era before air conditioning, this practical form of insulation effectively cooled structures by adjusting the humidity inside the building: the thick earthen walls absorbed excess moisture while protecting the interior from radiant heat. Contemporary architectural design in Louisiana follows conventional methods used in other parts of the American South, forgoing bousillage for fiberglass insulation and brick, wooden, or sheetrock walls.