Brotherhood of Timber Workers

An integrated labor union violently suppressed by lumber barons.

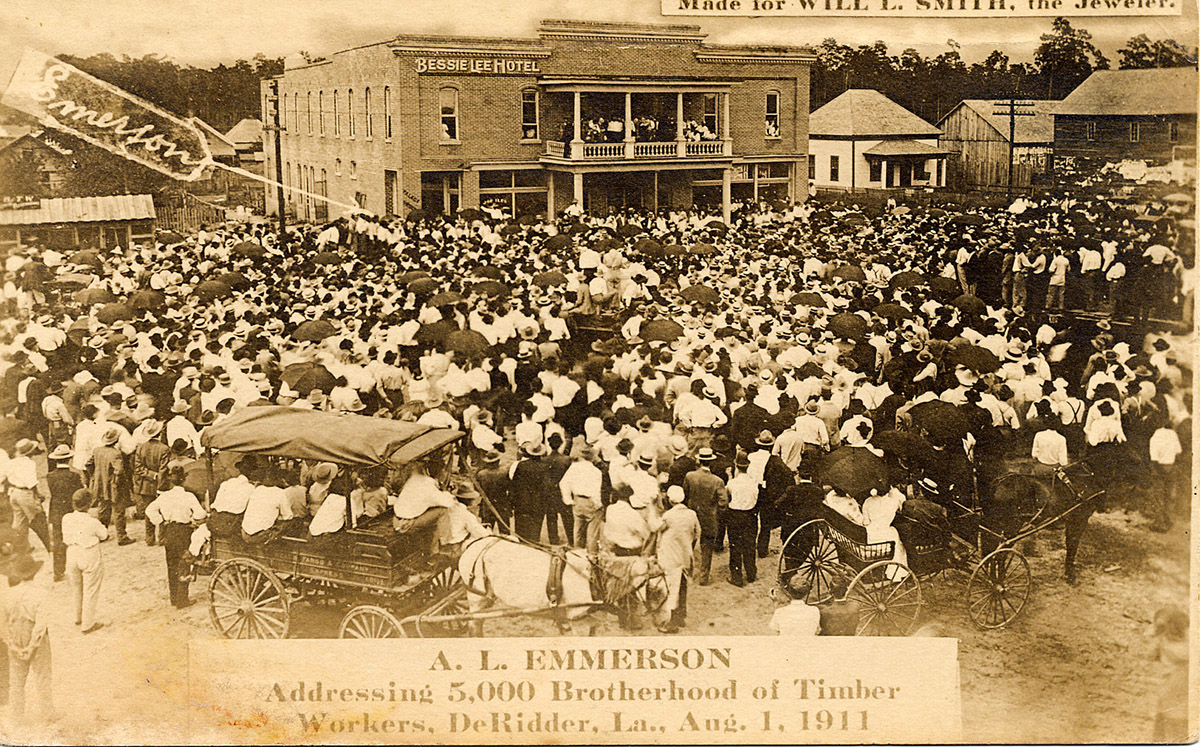

Frazar Memorial Library, McNeese State University

A. L. Emmerson addressing 5,000 Brotherhood of Timber Workers, 1911.

The Brotherhood of Timber Workers (BTW) (1910–1916), headquartered in De Ridder in Beauregard Parish and Kirbyville in East Texas, was an industrial labor union formed by employees of logging companies. Because about half the logging labor force was African American, membership was open to Black and other nonwhite workers as well as white workers, an unusual phenomenon in the Jim Crow South. The BTW sought to improve the deplorable living and working conditions that laborers were forced to endure. Lumber mill owners fought the union by hiring untrained armed guards, touching off what is often referred to as the Louisiana-Texas Lumber War of 1911–1912. Those same thugs assassinated or attempted to assassinate BTW leaders, some of whom were shot to death in the back as they tried to flee. The timber workers’ dream of a permanent organization through which they could bargain collectively and peaceably with their employers was destroyed by the lumber companies’ unified campaign of disinformation, espionage, blacklisting, and outright violence.

When Lumber Was King

In the early twentieth century, the timber industry was relatively new to Louisiana. Most of the state was still heavily forested in the years after the Civil War. The expansion of the railroad network in the 1880s and the magnificent untouched stands of longleaf yellow pine attracted lumber barons flush with profits from having deforested the Midwest and North. These “Michigan men” (as they were often called) saw gold in Louisiana’s Piney Woods. Transporting their entire mills down South on the railroads and bringing both capital and expertise, lumber barons worked with railroad companies to build spur lines to penetrate old-growth forests. (In fact, the railroad and timber industries often shared board members and mutual financial benefits.) This allowed for the efficient transport of cut logs to the lumber barons’ nearby mills. While sawmill owners earned handsome dividends exploiting Louisiana’s natural resources, they did not share that bounty with their workforce—all-male logging crews—who worked long hours for low wages in extremely dangerous conditions.

Company Towns and “Robberseries”

In those forested areas of the state that were largely unpopulated, lumber barons had to build houses and provide nearly all services to their employees. While the owners considered this a benevolent gesture, it meant the company had a monopoly on private enterprise in company towns. This allowed them to charge workers inflated prices for every service the company provided—all of it deducted from their pay. The men earned about $1.50 per day for eleven hours, six days a week (a 66-hour-work week)—but, to make matters worse, they were paid irregularly in company-printed scrip rather than in legal tender. Not knowing when or how much they would get paid after fees were deducted, workers were forced to buy on credit from the commissary (company-owned store), or “robberserry,” as the men called it, at exorbitant interest rates. In company-provided mess halls, the food was terrible and often rotten. In addition to charging employees above average prices for food and housing, owners deducted high insurance fees to pay the salaries of doctors, who were hard to find in an emergency since the company hired only one doctor to serve many lumber camps, and for hospitals that were too far away to save a seriously injured man. Conditions in “skidder towns” —logging camps that were picked up and moved from one location to another—were notoriously crowded and unsanitary. There, men lived in hastily constructed bunkhouses without enough room to get to their own bed without crawling over the others. Transient laborers were expected to bring their own sleeping gear, which they carried on their back from one camp to another.

Company Organization

In 1906, in response to a series of strikes, mill owners formed a cabal, the Southern Lumber Operators Association (SLOA) “to resist any encroachment of organized labor.” It taxed member mills to raise money for the purpose of fighting employees’ attempts to organize. SLOA used that fund to employ spies (known as operatives) to infiltrate union meetings and turn over the names of attendees and organizers, and to hire untrained private police forces (“guards”) to threaten union organizers with bodily harm. It also used the fund to compensate the owners who shut down their mills during the BTW threat.

BTW’s Formation, Membership, and Goals

Despite the risk of being laid off and turned out of their homes, workers in Texas and Louisiana organized the BTW in 1910–11, inviting farmers, local political leaders, and, later, women to join and pay dues. In 1910 the union claimed it had organized between 90,000 and 125,000 members. The lockouts, blacklists, and physical violence against members, however, reduced the number of dues-paying members to about five thousand by early 1912, a small number compared to most other unions at the time. Women members were deployed to help defend the men against violence (though this seldom worked), to assist strikes, and to recruit new members. Both men and women joined picket lines in support of striking workers.

BTW asked employers for guarantees of basic American freedoms: freedom of speech, assembly, and trade. Free speech meant they wouldn’t be assaulted for challenging the owners’ exploitative methods. Free assembly meant they could organize meetings without being fired, and free trade meant they had the right to shop in the store that offered the best goods at the best prices and not be forced to buy from company-owned stores. They also wanted the right to organize and bargain collectively. They wanted an end to compulsory doctor’s fees and hospital dues; to high commissary prices, interest rates, and rents; and to be paid regularly in United States dollars rather than in scrip. They requested a maximum workday of ten hours, improved sanitary and living conditions, and recognition for their union.

The BTW attracted local socialists, as De Ridder was the headquarters of a strong Socialist Party. Located in nearby Vernon Parish was America’s longest-lived socialist community, the utopian New Llano Cooperative Colony. With socialism “in the air,” there was nothing extraordinary about the BTW’s vote in 1912 to affiliate with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a Socialist-led national labor union. The SLOA used this alliance, however, as ammunition to portray the union men as violent revolutionaries who wanted to overthrow democratic governments—which was not true.

SLOA had a tremendous financial advantage over the BTW, having amassed more than $175,000 by 1911, whereas the BTW was able to raise little more than $3,000 per year from union dues, nearly all of which it spent to assist striking workers. Owners’ techniques of firing and blacklisting union members (meaning they would be refused employment in the industry forever), of shutting down mills where the BTW was active (known as a “lockout”)—thereby depriving the BTW of badly needed dues and members—and importing scabs (non-union labor), usually Black men, crippled union organizing efforts. Virtually all mills employed lockouts when they sensed growing union activity, throwing thousands of workers out of work.

However, the death knell of the BTW was company-sponsored violence. Owners deputized hundreds of untrained “police” in the name of the State of Louisiana and used force to break up union meetings.

A series of strikes and the arrest of dozens of workers following the Grabow Riot or “massacre” (as the workers called it) bankrupted the BTW. Though it limped along for a few more years, it officially disbanded in 1916. The owners had won, completely. The BTW got nothing for the workers, whose conditions and wages continued to deteriorate until demand for lumber increased during World War I.