Carpetbaggers and Scalawags

“Carpetbagger” and “scalawag” were derogatory terms used to describe white Republicans from the North or southern-born radicals during Reconstruction.

This entry is 7th Grade level View Full Entry

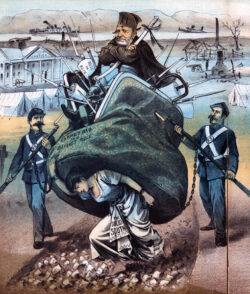

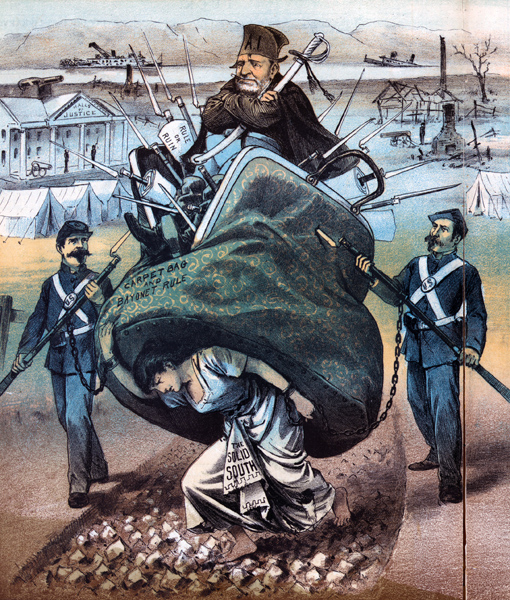

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

A political cartoon depicting a carpetbagger entitled “The ‘Strong’ Government,” by James Albert Wales, published in “Puck” on May 12, 1880.

Where did the terms “carpetbagger and “scalawag” come from?

“Carpetbagger” and “scalawag” are mocking terms that southern Democrats, or conservatives, applied to white Republicans, or radicals, during Congressional or Radical Reconstruction. A carpetbagger is a Republican who immigrated to the South from the North; a scalawag is a southern radical.

What changes did the Civil War bring to southern politics?

Former Confederate states were instructed to elect delegates to constitutional conventions and adopt new constitutions under the Reconstruction Act. As a result of Confederates losing the right to vote, Republicans dominated the conventions of 1867 and 1869. It was in these conventions that Black politicians, northern newcomers, and native-born radicals began to exert real political power. Counter-Reconstruction began in response to these conventions.

Although it wasn’t the case in Louisiana, across the South the largest single group of Republicans elected to the conventions were native white southerners. These people had been Unionists during the Civil War. Democrats in the Deep South used the word “scalawags” to discredit the conventions and their participants. Scalloway, an old Scottish village known for scraggly, inferior livestock two centuries before, probably inspired the word. “From time immemorial,” recalled one Mississippi editor, “scalawag” referred to “inferior milch [milk] cows in the cattle markets of Virginia and Kentucky.” However, the word also came to mean any unemployed bum or good-for-nothing person on the fringe of human society. In early 1868 an Alabama editor further refined scalawag’s meaning:

“Our scalawag is the local leper of the community. Unlike the carpetbagger, he is native, which is so much worse. Once he was respected in his circle . . . and he could look his neighbor in the face. Now, possessed of the itch of office and the salt rheum of Radicalism, he is a mangy dog, slinking through the alleys, haunting the Governor’s office, defiling with tobacco juice the steps of the Capitol, stretching his lazy carcass in the sun on the Square, or the benches of the Mayor’s court.”

In labeling native-born radicals as scalawags, southern newspaper editors created a powerful and enduring Counter-Reconstruction symbol.

How did scalawags and carpetbaggers influence Louisiana’s politics?

In Louisiana most scalawags were Unionists. A few of these individuals came from the upstate cotton region, such as James Madison Wells (governor during Reconstruction) and James G. Taliaferro (president of the constitutional convention of 1867–1868). The majority, though, were products of the northern-born and foreign-born communities of New Orleans and southeastern Louisiana. In antebellum New Orleans, northern-born migrants dominated business, professional, and civil life. Their northern and foreign backgrounds made them skeptical of secession. They lived and worked in one of the South’s most cosmopolitan cities. Northerners and foreigners transplanted during the war became Unionists and then Republican scalawags afterward. According to a study of 97 New Orleans Unionists, more than 81 percent were born outside the eleven Confederate states. German-born Michael Hahn was Louisiana’s wartime governor. Pennsylvania native Thomas J. Durant led the Free State movement, which sought to establish a Unionist government under federal occupation that would abolish slavery. Only one of the seven state officials who headed Louisiana’s Free State government in 1864 was a native southerner.

In Louisiana, Unionists/scalawags had their greatest influence between 1862 and 1867. Black politicians dominated the radical constitutional convention of 1867–1868. Between 1868 and 1877, scalawags held most of the seats in the state legislature, but power didn’t follow. Radical Reconstruction was largely controlled by carpetbaggers.

During or shortly after the Civil War, several thousand northerners migrated into the South. The great majority of these men had served in the Union Army and seen duty in the South. They were men in their twenties and thirties who saw the postwar South as “a new frontier, another and better West.” They came as cotton planters, businessmen, teachers, lawyers, physicians, and so on. As a group, they were well educated; indeed, they were probably the best-educated class of men in American politics, with many of them having college educations. These northern migrants were a minority, though a very influential minority, at the Reconstruction conventions.

In late 1867 an Alabama editor coined the word “carpetbagger” to describe them, a term the New Orleans press quickly adopted. In December 1867 the New Orleans Commercial Bulletin wrote a classic description of “the volatile patriots who come from the North to reconstruct the South upon a proper basis. . . . The man with the carpet bag has very little ‘whereby he may be attached.’ He is prospecting politically. If he finds a living without capital or labor, he hangs up his carpet bag.” But “if times are hard or troubles are impending, his ‘shirt for superfluity’ is called in from the wash; his bill, settled or unsettled, offers little impediment, and he may take the evening train.” Such northerners “go through the South to put up constitutional machinery, just as they might be sent out to put up lightning rods or cotton gins. They come as shadows, but they sometimes depart full and well stuffed.” Like that of the scalawag, the image of the greedy carpetbagger would be immortalized in the history of the era.

New Orleans was occupied by Union forces in May 1862. During the long occupation, thousands of federal soldiers, treasury agents, planter lessees, and other northern officials lived in the city. Consequently, carpetbaggers in Louisiana were more numerous and powerful than anywhere else. Both Louisiana governors under Radical Reconstruction, Henry Clay Warmoth (1868–1873) and William Pitt Kellogg (1873–1877), were carpetbaggers. The state elected three US senators in the radical years, all carpetbaggers. Ten of the thirteen congressmen sent to the US House of Representatives in the period were carpetbaggers. Northerners were always a small minority in the state legislature, but the Speaker of the House was a carpetbagger. Also in New Orleans, carpetbaggers controlled the Custom House, Mint, Post Office, Land Office, Internal Revenue Service, and Fifth Circuit Court. A group of federal employees known as the Custom House Ring dominated state politics in the early 1870s, driving Governor Warmoth from office and paving the way for William Pitt Kellogg, a former port collector. In the 1870s constant infighting among Louisiana carpetbaggers undermined progress during Reconstruction.