Clay Shaw

Clay Shaw is the only person tried on charges related to an alleged conspiracy in the November 22, 1963, assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

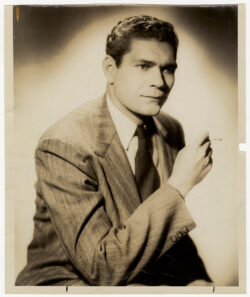

National Archives and Records Administration

A portrait of Clay Shaw, undated.

Clay Lavergne Shaw is the only person tried on charges related to an alleged conspiracy in the November 22, 1963, assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Shaw was born in Kentwood on March 17, 1913, the only child of Alice Herrington Shaw (1888–1973) and Glaris Lenora Shaw (1886–1966). By 1920 the family moved to New Orleans, where Shaw attended elementary school and graduated from Warren Easton High School in 1928. Shaw was employed by Western Union in New Orleans and was transferred to New York City by the company in 1935. Though he dabbled in theatrical and literary pursuits in both cities, he held professional positions in advertising and public relations.

Shaw enlisted in the US Army in 1942 and was promoted to second lieutenant the following year. He honed his organizational abilities while serving as aide-de-camp to General Charles Thrasher, whose troops organized support and supplies for the D-Day invasion. Before the war’s end Shaw was promoted to major. France awarded him the Croix de Guerre, and he earned a Bronze Star and Legion of Merit from the US Army before his 1946 discharge, after which he returned to New Orleans.

Shaw became managing director of a then-fledgling International Trade Mart. There, he oversaw the development of the organization’s first location, which opened in 1948. Some of his most enduring professional accomplishments include facilitating trade with Latin American companies and helping to secure financing and tenants for the thirty-three-story International Trade Mart Building. Shaw retired from International Trade Mart in 1965.

Shaw was also passionate about restoring derelict French Quarter properties, especially those with a historic association, including the Audubon Cottages on Dauphine Street and the Spanish Stables complex on Governor Nicholls, outside which a plaque commemorates Shaw’s preservationist activities.

Arrest and Prosecution

Given his high profile and generally favorable reputation, Shaw’s March 1, 1967, arrest on charges of conspiring to kill President Kennedy came as a shock to many New Orleanians. His identification as a suspect grew out of society’s prevalent homophobic prejudices and his status as a closeted gay man. Despite the French Quarter’s twenty-first-century reputation as a gay-friendly enclave, a broader culture of homophobia and intensive police harassment of gay-friendly gathering spots surged in New Orleans in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Jim Garrison, who had ordered Shaw’s arrest, had been elected district attorney in 1962 and was re-elected twice before leaving office in 1974. Although the escalation of arrests and harassment of gay men was not a direct result of Garrison’s election, when his investigation into a possible assassination conspiracy began in 1966, his investigators focused their attention on stories told about a possible connection between New Orleans–native Lee Harvey Oswald, the president’s alleged assassin, and a shifting roster of possible accomplices in the city’s gay community. Records from Garrison’s investigation confirm that Shaw was a suspect because he shared some characteristics—including his sexuality and ability to speak Spanish—with alleged Oswald co-conspirator Clay Bertrand.

Once Shaw was arrested, Garrison confirmed that he believed Shaw, using the alias Clay Bertrand, had discussed how to kill Kennedy with Oswald and another local gay man named David Ferrie. By the time of Shaw’s arrest, both Ferrie and Oswald were deceased. Only a single eyewitness to that critical, conspiratorial conversation ever emerged. Perry Raymond Russo’s testimony identifying Shaw as an assassination conspirator was elicited through means that included questioning while being administered sodium pentothal (an alleged “truth serum”) and during several hypnosis sessions overseen by the district attorney’s investigators.

Despite the scarcity of witnesses who could place Oswald, Ferrie, and Bertrand together in a conspiratorial conversation or act, Shaw’s prosecution proceeded, as did efforts by the District Attorney’s Office, to use Shaw’s sexuality to make him a plausible suspect in the minds of many who believed that homosexuality and deviant criminality often went hand in hand.

Shaw’s case went to trial in early 1969. On March 1, 1969, two years to the day after his arrest, Shaw was found not guilty in a unanimous jury verdict that took less than an hour to come in. Despite the resounding nature of his exoneration, Garrison ordered Shaw re-arrested and charged with perjury three days after the trial ended. Shaw and his attorneys had sought federal intervention in his case since its earliest days, arguing that his civil rights were being violated. However, it was not until 1972 that a federal court ruled in his favor, issuing a blistering decision barring Garrison’s office from further prosecuting Shaw in matters related to Kennedy’s assassination.

Aftermath

Shaw filed a $5 million civil suit against Garrison, Russo, and several other individuals who had abetted his prosecution. Before the case concluded, Shaw died on August 15, 1974, from metastatic lung cancer. Attorney Edward Wegmann fought valiantly to keep Shaw’s civil claim viable in the wake of his death. Despite those efforts the case ended when the US Supreme Court ruled against Shaw in 1978 because he had no survivors that met the heirship categories outlined in Louisiana civil law. According to critical coverage of the decision in the New York Times, Shaw had been “a homosexual man who many think was selected for prosecution because of his vulnerability, [he] left no survivors.”

In ensuing decades Garrison and those who favor his theory of a New Orleans–based assassination conspiracy supported by federal intelligence agencies, particularly the CIA, continued to cast suspicion on Shaw in books, films, and documentaries. The most spectacular late-twentieth-century example came with director Oliver Stone’s 1991 film JFK. Based in part on Garrison’s 1988 book On the Trail of the Assassins: One Man’s Quest to Solve the Murder of President Kennedy, the film trafficked in the same homophobic stereotypes that animated Garrison’s investigation. Contemporary defenders of Garrison’s theories and Stone’s depiction disavow the homophobia that lay at the center of the Garrison investigation, though they continue to advocate for the probability of a New Orleans–based conspiracy that involved three men, two of whom (Shaw and Ferrie) were gay and another (Oswald) who was alleged to be.

After having lived a distinguished life, Shaw’s unfortunate placeholder in American history remains tethered to his shoddy treatment at the hands of a conspiracy-minded district attorney and a failed prosecution that, nevertheless, continues to provide fodder for assassination conspiracy advocates.