Late Twentieth-Century Louisiana

Louisiana entered the 1960s behind the national curve in postwar development but poised for dramatic progress.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

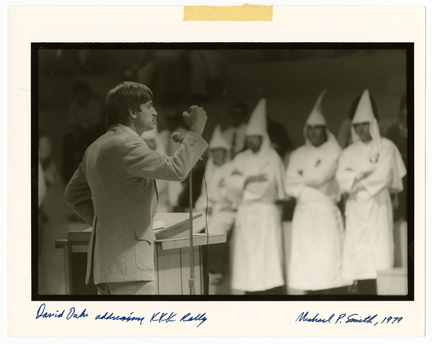

David Duke Addressing a KKK Rally. Smith, Michael P. (Photographer)

Louisiana entered the 1960s behind the national curve in postwar development but poised for dramatic progress. The oil and gas industry’s expansion, particularly offshore, stoked an economic boom that buoyed the state for two heady decades before temporarily stalling in the 1980s. As television made its way into most homes—including those in the swamps and bayou lands of the southern part of the state and the rural backwoods of the north—it exposed formerly isolated Louisianans to mainstream American culture and entertainment like never before. Major transportation improvements spurred regional growth, most notably along the east-to-west corridors of Interstate 10 across South Louisiana and Interstate 20 across North Louisiana; as the century drew to a close, the north-to-south Interstate 49 was finally completed, linking Shreveport and Lafayette. The state was a major battleground in the fight for civil rights; after many difficult years spent in the campaign to desegregate schools and other public facilities, New Orleans voters would elect a succession of African American mayors, and African Americans would be elected to Congress from both the New Orleans and Baton Rouge regions. The arrival of the National Football League’s New Orleans Saints in 1967 made Louisiana a major league sports venue; the opening of their new home, the Louisiana Superdome, in 1975 jump-started a downtown revitalization that would continue with the development of a riverfront convention center repurposed from the disappointing 1984 World’s Fair.

The 1960s witnessed two of the most dramatic events in US history—the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and the landing of American astronauts on the moon—and Louisiana had a role in both of them. Kennedy was killed in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963, and within hours, authorities arrested New Orleans native Lee Harvey Oswald for the shooting. Oswald had spent most of his childhood in New Orleans; he lived there for two brief periods as an adult, leaving the last time just two months before the assassination. Two days after his arrest, Oswald was shot to death on live television by Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby. New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison soon rose to national prominence for alleging that Oswald had been part of an extensive conspiracy, hatched in New Orleans, to kill the president. New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw was indicted in 1967 and accused of plotting to murder Kennedy. After a sensational trial in early 1969, a jury deliberated less than an hour before finding Shaw not guilty. Later that year Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin set foot on the moon, crowning a decade-long program of space exploration that began with a twenty-minute space flight by Mercury astronaut Alan Shepard in 1961. The Saturn booster rockets that propelled Apollo astronauts to the moon were built in New Orleans at the National Aeronautic and Space Administration’s Michoud complex, which employed thousands of South Louisiana residents. With the conclusion of the Apollo moon missions in 1972, the Michoud plant converted to the construction of external fuel tanks for the space shuttle program, which was inaugurated in 1981.

Civil Rights Battleground

Throughout the 1960s the fight for racial equality did not come easily. At the start of the decade, protests against the integration of two New Orleans schools, McDonogh 19 and William Frantz, in 1960 prompted bitter resentment and episodic racial violence. New Orleans Mayor deLesseps Morrison, who tried to downplay the severity of the violence, is often criticized for his ineffective leadership during the crisis. Nonetheless, with police protection and the strong arm of federal authority in place, the unrest dissipated by the end of the year. Events at these first two schools paved the way for more peaceful integration efforts the following year; 1961 witnessed the desegregation of additional New Orleans public schools, this time without significant turmoil.

Elsewhere, Judge Leander Perez held Plaquemines Parish in a segregationist grip, defying federal authorities and ultimately being excommunicated for his racist views by the Catholic archbishop of New Orleans. Discord in Bogalusa mounted as the local Ku Klux Klan aggressively threatened area blacks, prompting the formation of the Deacons for Defense, a group of armed blacks devoted to protecting their community from further injustices. Passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, both of which were enforced with the full strength of the federal government, more than any other factors helped to end de jure segregation in Louisiana.

Gov. John McKeithen fomented less agitation than did many of his southern colleagues, a fact that kept at least a partial lid on violence when compared with the state’s Deep South peers. In 1967, when Bogalusa civil rights leader A. Z. Young orchestrated a march from Bogalusa to Baton Rouge through territory considered a stronghold of intolerance, McKeithen made sure that state police shielded the demonstrators from violence. From 1964 to 1972, his approach to the state’s racial problems derived from a simple economic reality. Louisiana was poor, lacking in the industry necessary to forge a robust, diversified economy. Ever alert to the impact racial moderation would have on the state’s economic future, McKeithen sought to quell racial agitation before it spiraled out of control. Racial problems would persist, but the days of governmentally mandated discrimination were ending. With the rapid expansion of the black electorate in the late 1960s, the course of Louisiana politics changed forever.

Aside from social issues, McKeithen’s legacy also includes the Superdome, which he championed as a bigger-and-better response to the country’s first domed stadium, the Houston Astrodome. Built for $163 million and opened in 1975, the Superdome eventually would host seven of the ten Super Bowls staged in New Orleans—more than any other stadium—as well as a Rolling Stones concert that drew more than 87,500 people in 1981, a youth rally by Pope John Paul II in 1987, and the 1988 Republican National Convention.

New Orleans, long dominated by the city’s white minority, elected Ernest “Dutch” Morial as its first black mayor in 1977. Morial’s victory marked the culmination of a process that began with the integration of New Orleans schools in the 1960s. From the late 1960s through the 1970s, meanwhile, many white New Orleanians fled the city, primarily to adjacent Jefferson Parish, in the wake of integration and in the face of mounting crime. This migration also shifted the metropolitan area’s primary retail shopping axis from Canal Street in downtown New Orleans to Veterans Highway in suburban Metairie. Consequently, as Morial took office, the city was heading toward a fiscal crisis due to the loss of a large portion of its tax base. Its population peaked at 629,000 in 1960; by the time Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005, even with the growth of population in New Orleans East, it had contracted to 454,000.

Many whites who left urban centers such as New Orleans to avoid integration also found their political allegiance shifting as well. The Republican Party, long anathema in the state following the excesses of the Reconstruction era, made a strong comeback in Louisiana. At its heart, the Republican resurgence stemmed from much more than just disaffection with the national Democratic Party’s embrace of civil rights; it resulted from the pervasive democratic liberalism on all major issues of the day. Simply put, the Republican Party offered conservatives of every stripe an alternative to the big government expansionism typified by President Johnson’s Great Society programming. Long considered the ultimate refuge for white southerners, the Democratic Party no longer held sway over a majority of Louisiana voters. Republican successes marked the end of the Democratic Party’s monopoly of state-level offices that began in the days of Bourbon rule. By the 1970s, politicians seeking statewide office could no longer rely on the outdated rhetoric of race; they had to address themselves to a myriad of issues in the face of an expanded and often ideologically sensitive electorate.

The Edwin Edwards Era

Despite the growing resurgence of the Republican Party, the 1971 election of Cajun Democrat Edwin Edwards as governor ushered in an era of lavish government spending, which was predicated on a robust economy rooted in natural resources and on greater African American participation in Louisiana government. Before his career came to an end, Edwards would serve an unprecedented four terms as governor. Perhaps most important in securing the short-term economic prosperity of Louisiana, Edwards linked the state’s severance tax, which was formerly connected to the amount of the commodity extracted, to a percentage of its market value. As the rest of America struggled with recession and an oil crisis in the late 1970s, Louisiana petroleum became a much sought-after commodity. Edwards dramatically increased state spending once the oil boom brought unparalleled prosperity to a state long accustomed to austerity. Under Edwards, Louisiana rewrote its outdated 1921 Constitution and replaced it in 1974 with a more streamlined version that represented an important step toward modernizing the state and eliminating much of the cronyism for which it was notorious. Louisianans could look back on eight years under Edwards and rightfully claim that things had improved—that their standard of living had gone up and that they were undeniably better off than before. When one considers that all of the Edwards-era expenditures did little to lift Louisiana out of the bottom in almost all quality-of-life categories, it underscores just how far behind most of America the Pelican State was.

Edwards’s rise to power coincided with an emerging cultural renaissance among South Louisiana’s Cajun people. After decades of suppressing their native French language and traditions in response to the state school system’s English-only mandate of the 1920s and postwar pressure to conform to mainstream America, Cajuns—particularly younger ones—rediscovered their unique music, language, and other cultural touchstones. The Council for the Development of French in Louisiana (CODOFIL) was established as a state agency to promote the instruction of French in Louisiana schools. The first Tribute to Cajun Music Festival, sponsored by CODOFIL, was staged in Lafayette in 1974; now known as Festivals Acadiens et Creoles, it is among the state’s largest and most popular free music festivals.

Despite enormous popular appeal, the flamboyant Edwards faced accusations of misconduct that steadily grew over the course of his lengthy political career. After Edwards served the constitutionally prescribed limit of two consecutive terms, Republican Congressman David Treen was elected governor. Republican success in the 1979 election, presaging the “Reagan revolution” of conservative policy-making that followed Ronald Reagan’s election as president in 1980, marked the first time that the GOP controlled the governor’s mansion since the bitter Reconstruction era. Treen began his term by enacting a tax cut, and the state Department of Environmental Quality was created during his administration. But the oil bust of the early 1980s sent unemployment skyrocketing and state finances into a tailspin, and Treen struggled to connect with Louisiana voters. Polls showed state residents considered Treen more honest, but they favored the rakish Edwards. After sitting out a term, Edwards launched a spirited campaign against Treen in 1983 that ended Louisiana’s brief flirtation with its first Republican governor.

From Boondoggle to Boon

New Orleans hosted the 1984 World’s Fair, with the theme “The World of Rivers: Fresh Water as a Source of Life.” Seven million people attended the fair during its six-month run, but the attendance fell far short of the eleven million its promoters had projected. Although the event was popular with visitors, it proved to be a financial debacle, requiring a controversial bailout by state government at a time when state coffers were already dwindling. Economically disastrous at the time, the fair proved to be a boon in the long term. Once its facilities were converted into the city’s convention center, the foundation was laid for tourism to become among the most substantial factors of the region’s economy; by the 1990s New Orleans boasted 37,000 hotel rooms and was attracting up to 10 million visitors a year.

The optimism associated with Edwards’s laissez les bon temps rouler campaign of 1983 was short lived as the bottom continued to fall out of the petroleum market, owing in large part to a dramatic increase in Middle East drilling and federal deregulation. Ironically, Louisiana’s economic collapse coincided with a national economic boom. For too long, Louisiana had tied its fiscal future to a single, market-driven variable: the price of oil. New sources of revenue were desperately needed to help underwrite the state’s expenditures. With the economy in freefall, charges of political corruption against members of the Edwards administration soured many on the governor.

Charles “Buddy” Roemer, a bookish congressman from North Louisiana, emerged from a pack of challengers to lead Edwards in the 1987 gubernatorial primary, offering residents the hope of a scandal-free administration and an answer to the prevailing economic malaise. The incumbent Edwards, who had never lost an election, stunned voters by foregoing a runoff campaign and conceding the election to his little-known challenger. Inheriting a state on the verge of economic disaster with few alternatives—save for draconian cuts to education and health care—Roemer saw few options for digging the state out of its financial hole. In a surprising maneuver, he helped push through the legislature a long-stalled bill that would legalize “gaming” in an effort to generate revenue for the cash-starved state budget. A twice-weekly statewide lottery was launched and riverboat casinos set up shop throughout the state, but promises that gambling would offset the losses in oil revenue in the state budget proved to be overstated. Louisiana still struggled financially despite the infusion of capital brought by the return of gaming. In terms of education, the state’s schools still ranked near the bottom in achievement, just as its health care system struggled to accommodate the sick.

Roemer ran for reelection in 1991, but—as a moderate reform candidate with little to show for his term in office—he finished third in the primary. By virtue of the state’s open primary system, which spurned party primaries in favor of a free-for-all election with all candidates on the same ballot, the runoff pitted the two candidates from opposite extremes of the crowded field of candidates: ethically suspect Edwards against state representative and former Klansman and neo-Nazi David Duke. The electoral dilemma facing Louisiana voters attracted international attention. “I know some of you may have to hold your nose to vote for me but you should have no fear,” Edwards told a group of business executives. “This state means something to me, as it does to you. It means too much to all of us to give Louisiana to David Duke.” Edwards scored a convincing victory, but as his unprecedented fourth term in office proceeded, Louisianans found themselves less willing than ever to turn a blind eye to his political antics. Leaving office with a battery of new legal charges that would ultimately land him in prison, Edwards, like Roemer before him, left office without solving the state’s budget woes. Gaming failed to provide the staggering revenues promised, but it succeeded in snaring several politicians in federal investigations for their complicity in scandals that often involved organized crime.

Businessman Murphy J. “Mike” Foster, a longtime Democrat turned Republican, easily won election in 1995 on a promise of integrity and sound fiscal management. The popular Foster would go on to win reelection in 1999. He devoted considerable attention to investments in higher education, improving state education standards and giving Louisiana teachers pay raises—a decision applauded but still insufficient to place state educator salaries at the regional average. In all, Foster, like his predecessors, struggled to make Louisiana attractive to business and industry, but on average conditions did improve and the budget situation, if not solved, certainly steadied as the twentieth century came to an end.

The last three decades of the twentieth century saw continuing political evolution. Following a nationwide trend, women also became much more politically active. Such pioneering female politicians as Lindy Boggs and Mary Landrieu went on to regularly win reelection in a state that had once largely dismissed female office-holding, setting the stage for voters to elect the state’s first female governor, Kathleen Blanco, in 2003.

In the late twentieth century, Louisiana authors did much to polish the state’s reputation as a home for the arts. Louisiana State University historian T. Harry Williams won the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize for his definitive 1969 biography of Louisiana demagogue Huey P. Long. Novelist John Kennedy Toole was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize in 1981 for A Confederacy of Dunces, and Robert Olen Butler of Lake Charles won the 1993 Pulitzer for fiction for his short story collection, A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain. New Roads native Ernest Gaines and Walker Percy of Covington wrote some of the most enduring American novels of the twentieth century, inspired, in part, by their small-town experiences. New Orleans author Anne Rice staked out a lasting spot on the bestseller lists with her series of horror novels, beginning with Interview with the Vampire in 1976.

Long deemed a sportsman’s paradise, Louisiana continued to attract outdoorsmen to its unique woodlands and waterways. As industrial development and suburban growth encroached on formerly pristine habitats, many wilderness areas were threatened. Add to this the problems from decades of poor resource management, and the culture of indifference regarding preservation issues, and a major environmental crisis presented itself at the end of the century. By the 1990s, some Louisianans were acutely aware that the problems of coastal erosion, subsidence, and water quality needed immediate attention. Louisianans had to find a way to balance preservation with development in order to keep the state’s bountiful fisheries open and its populations in low-lying, levee-protected zones safe. Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita in 2005 and the British Petroleum oil spill in 2010 underscored that many of the problems that plagued the state in the late twentieth century remain unresolved in the twenty-first.