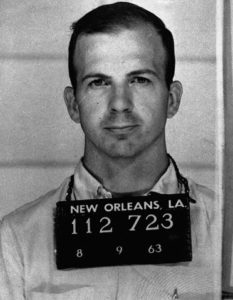

Lee Harvey Oswald

New Orleans-born Lee Harvey Oswald allegedly assassinated President John F. Kennedy in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963.

Wikimedia Commons.

Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested in New Orleans on August 9, 1963, after a scuffle with a rival political group while he distributed pro-Castro leaflets.

Lee Harvey Oswald, accused assassin of President John F. Kennedy, was born in New Orleans and drifted in and out of the city throughout the twenty-four years of his fateful life. Oswald spent his days in the shadows of society, only to thrust himself into history one day in Dallas, Texas, and forever imprint his name on the American psyche.

Born into an unstable family of modest means, Oswald as a child bounced among numerous family homes in and around New Orleans, Dallas, and New York City, even joining his older brother and half-brother for a time in an orphanage in New Orleans’s working-class Ninth Ward. After a tour of duty in the Marine Corps and a frustrating tenure as a defector to the Soviet Union, Oswald returned to New Orleans in 1963 and began to support the Cuban revolution of Fidel Castro. After failing in September of that year to obtain a visa to enter Cuba, Oswald returned to Dallas and got a job at the Texas School Book Depository. From a sixth-floor window there, he allegedly fired the shots that killed Kennedy as the presidential motorcade drove past Dealey Plaza at midday on November 22, 1963. Oswald was arrested in a movie theater that afternoon, but just two days later he was murdered in the basement of the Dallas police headquarters. His abrupt death left a slew of unanswered questions about the killing of the thirty-fifth president and sparked an onslaught of assassination conspiracy theories—suggesting connections to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the Cuban government, the Mafia, and others—that continue to cast shadows over the nation’s history a half-century later.

Early Years

Oswald was born on October 18, 1939, to Marguerite Claverie, the widowed daughter of a New Orleans streetcar conductor. Her husband, Robert Edward Lee Oswald, had been an insurance premium collector; he died of a heart attack at the age of forty-three on August 18, 1939, just two months before Lee was born. The couple’s first child, Robert Jr., was born in 1934; Mrs. Oswald also had an older son, John Edward Pic, from a previous marriage.

As a single mother with a newborn, a five-year-old, and a seven-year-old, Mrs. Oswald faced mounting financial difficulties. She leased her house on Alvar Street to a doctor while shuttling her family to a succession of rental homes elsewhere in the city. As a temporary measure in 1942, she placed her sons Robert and John in the Bethlehem Children’s Home in the Ninth Ward. She paid $10 per month for each boy’s keep and provided clothes and shoes. She wanted Lee to stay there as well, but he was too young to be admitted. She soon found a job as a telephone operator, and her sister, Lillian Murret, babysat Lee often during this time. Throughout his life, Oswald would seek assistance from Lillian and her husband. Later, Oswald’s relationship with his uncle—Charles “Dutz” Murret—would interest conspiracy theorists because Murret was connected to the Marcello crime family and was a bookie in addition to his regular job as a longshoreman.

When Oswald turned three, he was old enough to join his brothers at the Bethlehem Children’s Home. His mother deposited him there the day after Christmas 1942. For a little more than a year he resided there, with short stays with his mother or the Murrets. As adults, John Pic and Robert Oswald Jr. recalled the orphanage as a pleasant place, partly because the brothers were together and the rules were not overly strict.

In 1943 Mrs. Oswald managed a hosiery store on Canal Street and eventually met Edwin A. Ekdahl, an electrical engineer from Boston who was working in New Orleans. By January 1944, the couple had decided to marry. Mrs. Oswald sold the Alvar Street house, took young Lee out of the orphanage, and moved to Dallas, where Ekdahl’s job had taken him. The older brothers stayed at Bethlehem to finish out the school year.

But the Ekdahls’ marriage soon fell apart. By 1946 Marguerite and her three sons returned to Louisiana, moving into a rental house on Vermont Street in downtown Covington. The older brothers were sent to a military boarding school in Port Gibson, Mississippi, but Lee attended Covington Elementary School, his second attempt at the first grade, since his initial year of school in Texas had not gone well. The Ekdahls reconciled early the next year, and Oswald moved to Fort Worth with his mother. The marriage ended for good in 1948; after the divorce, Marguerite returned to using the name Oswald. She and Lee stayed in Texas until August 1952, when they moved to New York City to be near John Pic, who by then was married and in the Coast Guard. Oswald got into trouble in New York for truancy, and he developed a fledgling interest in communism during this period after reading a leaflet about the pending execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who had been convicted of spying for the Soviet Union.

Eventually, Mrs. Oswald became worried that her fourteen-year-old son would be removed from her care, so she returned with him to New Orleans in early 1954. Oswald spent the eighth and ninth grades at Beauregard Junior High on Canal Street. He had few friends, but he did attend some meetings of the Civil Air Patrol, a group whose mission was to interest boys in joining the Air Force. This is where Oswald probably first met former commercial airline pilot David Ferrie, a figure of much interest to later investigators following Kennedy’s assassination. Oswald attended Warren Easton High School for one month before dropping out just before his sixteenth birthday. He spent the next year working bicycle delivery and stockroom jobs, and marking the days until he would be old enough to enlist in the Marine Corps, following the lead of his brother Robert.

Self-Proclaimed Marxist

Oswald enlisted in the Marines on October 24, 1956, six days after he turned seventeen years old. In weapons training, he qualified as a sharpshooter, and he was posted for a time as a radar operator—with high-level security clearance—at the Atsugi, Japan, Naval Air Facility. Atsugi also was the Asian base of operations for American U-2 spy planes, which routinely took surveillance photos from Russian air space. Oswald accidentally shot himself in the arm with a nonmilitary pistol in 1958, and he was court-martialed for illegal possession of a firearm. After assaulting a sergeant connected to the case, he was court-martialed a second time and jailed for several weeks. The experience left him bitter, and it was during this time that he began to openly espouse Marxism.

While a Marine, Oswald began studying Russian and making secret plans to defect to the Soviet Union. In August 1959, he requested a dependency discharge, citing an injury suffered by his mother. He was discharged from the Marine Corps on September 11. After an overnight stop to visit family in Texas, he proceeded to New Orleans, where he made travel arrangements for his defection to the Soviet Union. On September 20, Oswald left the United States on the France-bound freighter SS Marion Lykes. Oswald lied on the immigration questionnaire, claiming to be a “shipping export agent” who would be abroad for two months. From France, he crossed to England and then flew to Helsinki, Finland. There, he obtained a visa from the Soviet consulate, and he arrived in Moscow by train on October 16. The next day, he told his Intourist guide (official Russian agency assigned to tourists) that he wished to defect because he disapproved of the American way of life.

The KGB (the Soviet intelligence agency and secret police) was not impressed with Oswald and initially declined his request. Following a failed suicide attempt, Oswald turned up at the US Embassy and declared his intention to renounce his American citizenship, adding that he planned to share with the Soviets all he had learned during his time as a radar operator in the Marines. After details of the conversation were relayed to the Pentagon, the Marine Corps changed its radar codes and instituted “dishonorable discharge” proceedings against Oswald.

Eventually accepted by the Russians, Oswald was sent to Minsk, where he was given a job and an apartment and kept under constant surveillance by the KGB. He married a young Russian woman, Marina Prusakova, but became disillusioned with Soviet life and petitioned the US Embassy in early 1961—less than a month after Kennedy’s inauguration as president—for permission to return to the United States. In June 1962 Oswald finally was allowed by Soviet and US officials to return to America, bringing with him his wife and their infant daughter, June. Back in Dallas, Oswald befriended a small group of Russian immigrants, one of whom helped him get a job at a photo lab. At this time, Oswald’s interest in Marxism was rekindled, he became enamored with the Castro regime in Cuba, and he objected to the Kennedy administration’s involvement in the botched Bay of Pigs invasion. In February 1963, using an assumed name, he obtained by mail two firearms: a pistol and the Mannlicher-Carcano rifle that would be used in the attack on Kennedy nine months later.

Return to New Orleans

Oswald did not see New Orleans again until April 25, 1963, when he arrived at the bus station and phoned his Aunt Lillian to ask if he could stay with her and her husband. The Murrets were shocked to learn that he had returned to the United States, was married to a Russian woman, and had a baby girl. Lillian Murret told him he could stay with them while he was job hunting, but they did not have space for Marina and their daughter. His wife and child had to stay in Dallas until he found a New Orleans apartment.

On May 9, Lee landed a job as a machine greaser at the William B. Reily Company, a coffee roasting plant at 640 Magazine Street. He earned $1.50 an hour and soon found an apartment at 4905 Magazine Street for $65 a month. By May 11, his family had arrived from Texas.

Oswald’s employment in New Orleans did not last long; his job performance was poor and the coffee company fired him on July 19. He subsequently spent his days filling out unemployment forms and hanging around the Magazine Street apartment. Marina was expecting another child, and Oswald toyed with the idea of going back to Russia or maybe moving to Cuba.

Around this time, Oswald tried to set up a branch of the pro-communist Fair Play for Cuba Committee and ordered one thousand of their leaflets printed with the address 544 Camp Street. Paradoxically, at this time Oswald also attempted to cultivate friendships with anti-Castro Cubans in New Orleans by claiming he wanted to join in armed struggle against Castro. One of these anti-Castro Cubans, Carlos Bringuier, encountered Oswald distributing the pro-Castro leaflets on Canal Street. Bringuier and some friends got into a physical altercation with Oswald on the sidewalk. Police intervened; Bringuier and Oswald were hauled off to jail to spend the night. One of Dutz Murret’s friends bailed Oswald out of jail on August 10, 1963. Two days later, Oswald pleaded guilty to disturbing the peace and paid a $10 fine.

The street scuffle with the Cubans got Oswald the attention he wanted. On August 17, he appeared at WDSU radio station and was interviewed for the show “Latin Listening Post,” hosted by Bill Stuckey. Oswald and Stuckey talked for more than thirty minutes, and WDSU produced a four-and-a-half minute segment that was broadcast at 7:30 that night. Four days later, Stuckey arranged a live radio debate with Oswald, Bringuier, and Ed Butler, director of an anti-communist propaganda group, on a program called “Conversation Carte Blanche.”

Oswald’s whereabouts in late August and early September 1963 are not completely known. In its final report in 1979, the House Select Committee on Assassinations noted that it was inclined to believe that Lee Harvey Oswald made an appearance in Clinton, the seat of East Feliciana Parish, and talked to locals about getting hired at the state mental hospital in Jackson. However, the committee could not establish who accompanied Oswald on that trip. The identity of his companions, if any, is still debated. By September 25, Oswald disappeared from Louisiana and resurfaced a couple of days later in Mexico City, where he attempted unsuccessfully to obtain a visa to enter Cuba; he had hoped to join in the work of the Castro regime. He returned to Dallas on October 2. Twelve days later, he was hired as a warehouse clerk at the Texas School Book Depository. The next week, Marina gave birth to their second child, a daughter named Audrey, but the Oswalds were largely estranged by this time. Marina was living in a Dallas suburb with family friends Michael and Ruth Paine, and her husband had a room in a boarding house and only visited on weekends.

Fateful Day in Dallas

Reports of Kennedy’s impending visit to Dallas on November 22 were in the news for days beforehand, and Oswald followed the coverage intently. When the route of the presidential motorcade was reported in the press, he realized that he would have an unobstructed, lunch-hour view of the president’s limousine from the sixth floor of the warehouse where he worked. On the morning of November 22, he got a ride to work from a neighbor, explaining that the oblong, wrapped package he was carrying contained curtain rods for his room at the boarding house.

Investigators would conclude that at 12:30 p.m., three rifle shots were fired from the textbook warehouse window as the Kennedy entourage passed below. The first shot missed. The second wounded Kennedy and Texas Gov. John Connally, who was seated in front of the president and First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy in the convertible limousine. The third was a direct hit on President Kennedy’s skull.

Oswald fled the Texas School Book Depository, taking a bus and then a taxi to get to his boarding house, where he retrieved his pistol and left again. He was believed to have encountered police officer J. D. Tippit around 1:15 p.m. and shot him to death with the pistol. Oswald then slipped into a movie theater without buying a ticket. Someone called the police, and within minutes, after a brief struggle in the Texas Theatre cinema, he was arrested.

Two days later, Oswald was assassinated as police were leading him through the basement of the police headquarters in order to transfer him to the county jail. He was shot, live on national television, by Jack Ruby, a nightclub owner who was friendly with numerous police officers. Oswald never regained consciousness and was pronounced dead less than two hours later.

Oswald was buried in Rose Hill Burial Park in Fort Worth on November 25, the same day that Kennedy was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. There, an eternal flame was lit by Jacqueline Kennedy at the gravesite.

President Lyndon B. Johnson established the President’s Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy to investigate the case. The panel, known as the Warren Commission, was chaired by Chief Justice Earl Warren and also included congressman and future president Gerald R. Ford. It concluded in an 889-page report issued in September 1964 that Oswald acted alone. The crime remains unsolved in the minds of many, however, and it has spawned throughout the decades countless conspiracy theories about the shootings of both Kennedy and Oswald.

Most notably, Orleans Parish District Attorney Jim Garrison launched a high-profile investigation in late 1966 into possible ties between the New Orleans underworld and the Kennedy assassination. The investigation—which began with tips that David Ferrie might have been involved in the shooting of Kennedy—culminated in the trial of New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw in 1969. As part of the prosecution’s case, Garrison subpoenaed and showed in public for the first time the now-famous home movie documenting the assassination by onlooker Abraham Zapruder. Garrison attracted worldwide attention with his prosecution of Shaw, but the case unraveled in court and Shaw was unanimously acquitted by the jury in less than an hour.