Dunbar-Hunter Expedition

The Dunbar-Hunter Expedition was commissioned by Thomas Jefferson to explore and document the lower regions of the Louisiana Territory.

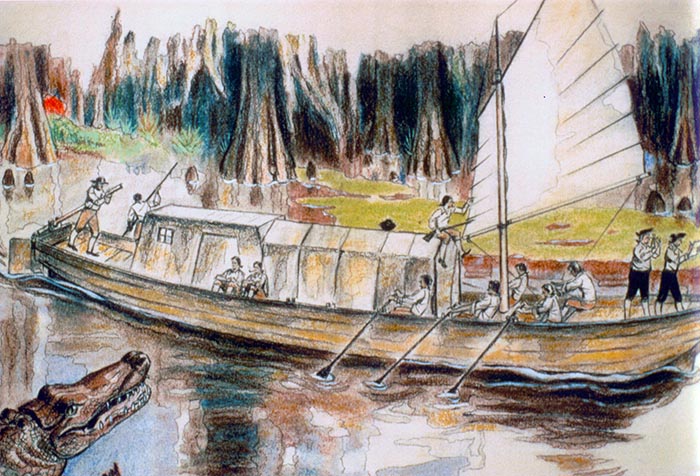

Courtesy of Unidentified

This drawing illustrates how the 1804–1805 Hunter Dunbar expedition may have appeared as the explorers traversed the lower Ouachita River.

The 1804–1806 expedition of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark from St. Charles, Missouri, to the Pacific Northwest is considered a milestone in the exploration of North America, yet their voyage was not the only one to venture into the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase territory. Conceived by President Thomas Jefferson to explore and document the geography, natural resources, and Native American cultures in the vast, unknown regions west of the Mississippi River recently acquired by the United States, Lewis and Clark’s probe is well known and heavily documented—but it was not a solo act. Jefferson also planned and executed—concurrently and with similar objectives—a southern version of the Corps of Discovery, as the Lewis and Clark entourage came to be known. Led by two prominent Scottish immigrants, William Dunbar and Dr. George Hunter, the venture in the lower regions of the Louisiana Territory was originally intended to trace the Arkansas and the Red Rivers to their sources. Had it succeeded as planned, it could have rivaled the Lewis and Clark expedition in scope; however, aggressive Osage Indians along these rivers thwarted the president’s scheme, and he redirected Dunbar and Hunter to explore the Ouachita River instead. Though scaled down, the modified expedition still gathered valuable scientific and geographic information that testified to the new nation’s potential.

The Explorers

William Dunbar (1749–1810) was born to aristocratic parents in Morayshire, Scotland. He was educated in Glasgow and London, and he had a lifetime affinity for the sciences. Seeking an adventurer’s life, he sailed to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, at the age of twenty-two. Two years later he was established on a plantation near Baton Rouge, where he engaged in farming and was a steadfast proponent of slavery. Dunbar later moved upriver, below Natchez, and acquired two plantations that totaled almost four thousand acres. Always experimenting with progressive farming practices, he gained prominence throughout the region for his business and scientific acumen. He was a surveyor for the Spanish government, and his inventions included a unique type of cotton press. Scientists traveling in the wilderness of the lower Mississippi Valley frequently visited Dunbar at his plantation home and sought his advice. Hearing of Dunbar’s reputation, Jefferson nominated him as a fellow in the prestigious American Philosophical Society. After several years of correspondence between the two men, Jefferson became convinced that Dunbar was the man to lead the southern expedition.

George Hunter (1755-1823) was also born in Scotland, but his family ranked middle class at best. As an apprentice, he learned the apothecary trade and brought those skills to America in 1774. He enlisted in the Continental Army during the American Revolution and participated in the battles of Princeton and Trenton. After the war he worked for a while as a ship’s surgeon before marrying and engaging in a variety of successful businesses as a chemist, apothecary, and trader. He occasionally took exploratory trips into remote areas of Kentucky and Illinois. As with Dunbar, Jefferson knew Hunter’s reputation. On April 15, 1804, President Jefferson penned a letter to Dunbar asking that he lead an expedition to explore the Red and the Arkansas Rivers. In it he stated that Dr. George Hunter would be his partner and chief counsel.

Preparations

When Congress appropriated three thousand dollars for the venture, Hunter immediately began preparations to obtain a suitable boat and other supplies in Pittsburgh. As for the boat’s design, Hunter described it thus: “This boat is 50 feet long on deck, 30 feet straight Keell, flat bottom somewhat resembling a long Scow … and furnished with a Stout Mast 36 feet long a sail 24 feet by 27 in the Chinese stile [sic].” The design turned out to be totally impractical for navigating shallow southern rivers. Meanwhile, Dunbar began researching the proposed expedition by interviewing people with regional knowledge. At this time Jefferson and Dunbar began to doubt the likelihood of a successful trip up the Red and the Arkansas Rivers: there were increasing reports of predatory behavior by a band of Osage and apprehension that Spanish authorities might challenge foreign travelers in their claimed territory. Concerned about the crew’s safety, Jefferson decided to postpone the expedition. Undaunted, Dunbar suggested a scaled-down mission to explore the Ouachita River to its purported source in an intriguing mountain valley laced with mineral-laden and healing hot springs. Jefferson agreed.

At St. Catherine’s Landing below Natchez, the crew—with three months’ provisions—assembled at the boat on October 16, 1804. The party consisted of Dunbar, two enslaved people owned by Dunbar. and a servant, Hunter, Hunter’s teenage son, and thirteen enlisted soldiers. At about 3 p.m. they pushed off into the ceaseless current of the Mississippi River.

The Expedition

To access the Ouachita River, the voyagers had to travel down the Mississippi River to the mouth of the Red River and then proceed upstream to its confluence with the Black River. Along the way, Dunbar and Hunter began their daily routine of recording the latitude and a description of soils, native plants and animals, and the general progress of their mission. Just before reaching the mouth of the Black River, the group captured a man named Harry, suspected of running away from slavery, and took him aboard. When they entered the Black River on October 19, the leaders had already realized two problems that could jeopardize the trip: the boat, as designed, was not fit for efficient travel on the shallow, meandering rivers; and the soldiers, lacking an officer for discipline, were reluctant to perform the hard labor necessary to propel the heavy craft upstream.

On October 23 the party reached the prehistoric mound complex now called the Troyville site. They gleaned information about the surrounding area from a Frenchman who had a cabin on the tallest mound and operated a ferry for the infrequent traveler trekking overland between Natchez and the Red River country. From him they learned that the distance to Fort Miro was fifty-three miles and that shallow rapids intervened between them and this first wilderness settlement. Later that evening, camp was made at the mouth of the Ouachita (spelled “Washita” at the time).

Arriving at the rapids on October 26 near present-day Harrisonburg, the party found the depth to be only one foot; as their boat drew two and a half feet, considerable effort was made to trench a passage through the barrier. Hunter complained that “the men seemed jaded or unwilling to work at it.” Continuing, on October 30 the boat was hailed by a man ashore claiming to be Harry’s enslaver, and Harry was turned over to the man. Struggling upstream through frequent shoals that required loading and unloading of the boats by the recalcitrant crew, the party poled into the frontier village of Fort Miro (also known as Ouachita Post at the time, and Monroe today) on November 6.

The following day Dunbar wrote, “Finding from past experience that the boat in which we have come up would be improper for the continuation of our voyage, we made enquiry this morning for other craft, but it appears there is no great choice of boats at this place.” They eventually found a large, shallow-draft barge for rent, but this new boat almost sank after they transferred their supplies into it. Following a thorough recaulking of the vessel, they proceeded on November 12 and soon passed the site of a land settlement scheme by Felipe Enrique Neri, the so-called Baron de Bastrop.

On November 15 the explorers crossed the modern boundary between Louisiana and Arkansas. Progress improved as the new craft had a draft of only one foot. The two leaders continued gathering data on position, air and water temperature, water depth, channel width, and the biodiversity of their surroundings. The crew often supplemented their basic larder with waterfowl and wild turkeys killed along the way. Then on November 22, near present-day Camden, Arkansas, tragedy struck. While reloading his pistol, Hunter was nearly killed when the gun slipped from his grip, discharged, and propelled the bullet and ramrod through his hand, and missing his forehead by less than an inch. His thumb and two fingers were badly injured, and the blast caused partial blindness and facial burns that incapacitated him for two weeks.

Passing the confluence of the Little Missouri River, the alluvial soils and sandbars began yielding to gravel bottoms and rock outcrops. They encountered occasional parties of hunters. Shoals and rapids increased, requiring the soldiers to tow the boat upstream from lines ashore. Finally, on December 6, near the mouth of Fourche au Calfat (Caulker’s Creek), progress via the river ended. A “pilot” hired at Fort Miro and familiar with the region led the group overland nine miles to the hot springs (in present-day Hot Springs, Arkansas).

For a month the expedition camped at the remarkable cluster of hot springs while Dunbar and Hunter conducted their scientific inquiries. Dunbar performed astronomical observations and Hunter analyzed the water chemistry. They made forays into the surrounding hills to assess minerals and geographic features. As winter hardened with frequent snowstorms, the party hauled their equipment back to the river and waited for a rise that would ensure their safety in the downstream rapids. On January 8, 1805, they departed downstream and homeward.

The return voyage was relatively uneventful and much faster than the upstream struggle. The party crossed into Louisiana on January 14; they arrived at Fort Miro at noon on January 16. Anxious to reach his home, Dunbar along with his servant and a soldier broke from the group at Fort Miro and hurried on to Natchez via canoe and horseback. He arrived on January 26. Hunter and the remainder of the group returned the rented barge and carried on in their original, unwieldy vessel, arriving at Natchez on January 31. On this day Lewis and Clark were overwintering their outbound expedition at Fort Mandan on the upper Missouri.

In the months following, Dunbar and Hunter prepared their reports and finalized their journals for submission to Thomas Jefferson. The president relayed the information to Congress, and in 1806 a detailed account of the expedition was published in Message from the President of the United States, Communicating Discoveries Made in Exploring the Missouri, Red River, and Washita, by Captains Lewis and Clark, Doctor Sibley and Mr. Dunbar with A Statistical Account of the Countries Adjacent.

The accomplishments of the Dunbar-Hunter expedition, though on a much smaller scale than those of Lewis and Clark’s epic journey, were nonetheless noteworthy. They gathered geographic data on a wilderness region that was later compiled into an accurate map. They were the first to scientifically document the marvels of the hot springs. Their observations provided valuable insight into the flora and fauna of the Ouachita River valley while it was still pristine. They verified for a young United States that the area was already well known and traveled by commercial hunters and traders, thus offering the possibility of flourishing settlements in the near future. Concerning the expedition’s role in the exploration of the Louisiana Purchase territory, President Jefferson wrote to Dunbar on May 25, 1805: “For this we are much indebted to you, not only for the labor and time you have devoted to it, but for the excellent method of which you have set the example and which I hope will be the model followed by others. We shall delegate with correctness the great arteries of this great country. Those who come after will extend the ramifications as they become acquainted with them, and fill up the canvas we begin.”