Fort Miro

Located on the site of present-day Monroe, Louisiana, Fort Miro was a late eighteenth-century Spanish outpost that served the Ouachita River valley.

Courtesy of Flickr

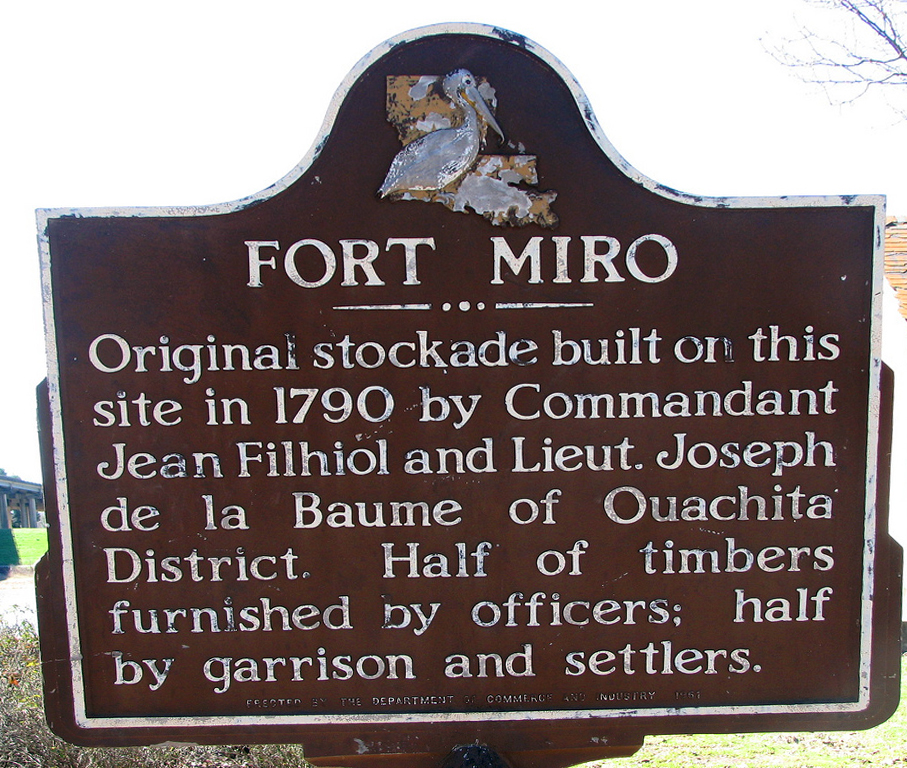

Fort Miro Historical Marker. Unidentified

Located within the present bounds of the city of Monroe, Fort Miro was a late eighteenth-century Spanish outpost that served the Ouachita River valley. Named after Gov. Esteban Miró, “Fort Miro” refers to both the actual fortification and the village that sprung up around it.

Beginnings

During the late 1700s, because the Spanish Crown faced increasing pressure from other imperialist European powers, the newly formed United States, and Native Americans, it sought to stabilize and secure its vast North American holdings. This demand resulted in the establishment of scattered posts, often led by a commandant with a garrison of soldiers that served as the seat of Spanish authority within designated geographic regions. Because of the terrain, most posts were situated along a waterway, the only feasible method of transportation at the time.

This political environment prompted Governor Miró to select Don Juan Filhiol, an officer at the well-established Opelousas Post, to found and serve as commandant of a new post in the remote Ouachita District, in what is today part of northeast Louisiana. Filhiol was charged with grouping the scattered inhabitants into civilized settlements, restricting aggressive English and American encroachment into Spanish territory, and promoting harmony with disgruntled Native Americans.

In 1783 Filhiol departed New Orleans via keelboat for the difficult wilderness journey with a few soldiers and slaves, a new wife, and provisions. The entire distance was upstream through the Mississippi, Red, Black, and, finally, Ouachita Rivers. Filhiol first established his base of operations at Ecore-a-Fabry (present-day Camden, Arkansas). Two years later, in 1785, he relocated downstream to the centrally positioned Prairie des Canots, an area of relatively high land on the east bank of the Ouachita, known to be a popular campground with Indians. Here, in a large, fertile prairie that encouraged agriculture, Filhiol officially planted the Post d’Ouachita for the Spanish King.

Building the Fort

In 1785 the entire Ouachita District held a non-Indian population of only 207. Filhiol quickly learned that congregating these scattered, free-spirited occupants into a civilized village would be no easy matter. Most were not of Spanish lineage and held a general distrust of authority of any type. Increasingly frustrated with those he considered immoral heathens, Filhiol tempted them with promises of a church for proper marriages and baptisms, and a schoolmaster to educate their children. There were few takers in the early years. Attitudes only began to change when the threat of Indian depredations increased, especially from the Osage who lived just upriver.

On August 25, 1790, Filhiol wrote Miró, “Some inhabitants have asked me for a fort … where hunters would be tranquil in leaving to know a refuge for their families existed.” Filhiol requested assets to construct the fort and suggested, “I beg of you to allow it to bear your name. That is your lawful due as settler of this country.” When Miró failed to reply, Filhiol wrote that he would build it himself with the help of settlers. He asked that Miró consider sending swivel guns and munitions to arm the fort, which he did.

Filhiol’s plans were to build a palisaded, ten-foot wall of vertical logs around his existing home and outbuildings. With a circumference of 680 feet, the structure would consist of 1,020 cypress and white oak logs. Filhiol and his lieutenant promised to supply at least half the logs, and seventeen area men were obligated to deliver twenty-five logs each. The plans soon went awry, and Filhiol wrote, “Thanks to the natural indolence of these people, the fort is not at the stage I had hoped, all the logs not yet having been brought.” Because many of the logs were never delivered, the plans had to be drastically altered. The final enclosure was constructed of horizontal logs with four covered bastions. Iron spikes were driven around the rim. With the exception of the gate hinges, which were still en route from New Orleans, the fort was completed in February 1791—mostly with funds and labor provided by Filhiol. From that point forward, the old name of Post d’Ouachita gave way to Fort Miro.

Heart of the Settlement

For ten years Filhiol conducted the business of the district from his home inside the fort. As the legal representative of the king, he was the law of the land. Within the fort, passports and business licenses were allotted, property deeds and verdicts issued, medicine dispensed, church services and markets held, and Indians mollified. In 1800, when Filhiol retired, his successors—Don Gillaume de la Baume and Don Vincente Fernandez Texiero—operated the fort in his tradition. Slowly the settlement grew. Storefronts and houses appeared on rough streets around the fort. A lasting change trailed the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. Representing the new owners, American Lieutenant Joseph Bomar arrived to take command of the region in 1804. Because it was built on Filhiol’s private property, Bomar did not occupy the fort. Instead, he built a new smaller stockade four hundred yards south for his garrison.

By this time, the fort had ensured the permanency of the yet-expanding community. The name, Fort Miro, continued to label the village until the river yielded up a most fantastic machine on a spring day in 1819. On May 1, the first steam-powered vessel to appear before the hamlet so astonished and impressed the citizens that they changed the name of their village to the name of the boat. The steamboat was the Monroe, itself named after the president of the United States.

In 1973 archaeologists attempted an excavation to locate the exact site of Fort Miro, but the dig was inconclusive.