Freedmen’s Bureau in Louisiana

After the Civil War, the Freedmen’s Bureau sought to provide social services to newly freed people, regulate contracts between laborers and employers, and protect citizens’ civil rights.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

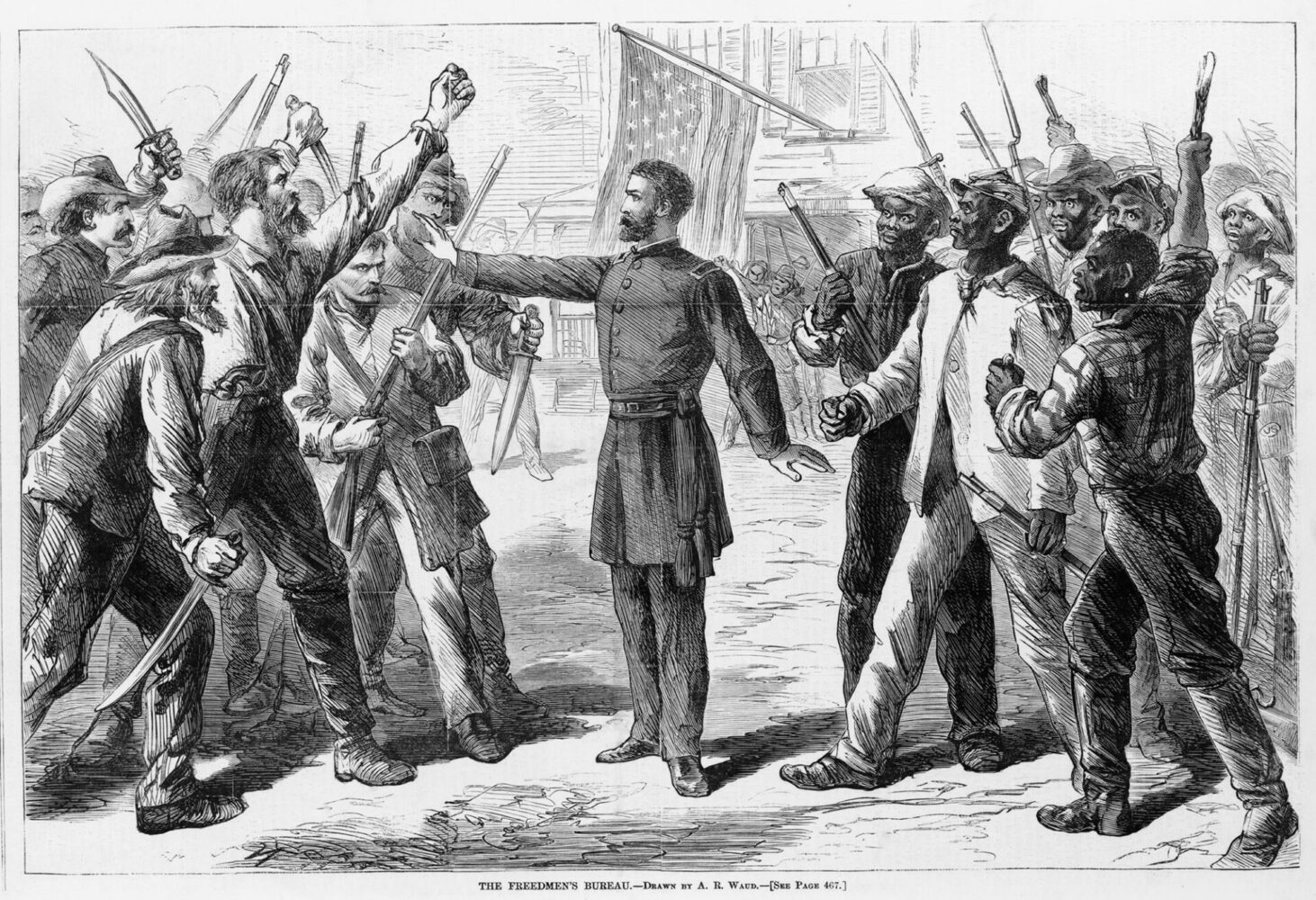

An illustration of a man representing the Freedmen's Bureau stands between armed groups of armed white and Black men, 1868. Alfred R. Waud, illustrator.

The Freedmen’s Bureau was a federal government agency responsible for formerly enslaved people, refugees, and abandoned lands between 1865 and 1868, though a couple of its functions continued to 1872. The bureau was crucial to Reconstruction after the American Civil War, as it tried to usher formerly enslaved people into a new era of citizenship and wage labor. With the official title Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, the Freedmen’s Bureau was a part of the US War Department. Its jurisdiction comprised the former Confederate states, which included Louisiana. The bureau administered a host of services for formerly enslaved people, including hospitals and schools. It also distributed rations, recorded marriages of formerly enslaved people, enforced labor contracts, and heard complaints about working conditions and civil rights violations. Because the Union army occupied large portions of Louisiana beginning in 1862, including New Orleans, the army started many activities that were eventually taken over by the bureau. The Freedmen’s Bureau represented a brief moment after the Civil War when the federal government sought to provide social services to individuals and families, regulate private contracts between laborers and their employers, and protect the civil rights of citizens.

The Freedmen’s Bureau placed assistant commissioners in each state and empowered them to administer the bureau’s services there through a complex web of personnel. In Louisiana, the assistant commissioner and his executive staff—superintendent of education, assistant adjutant general, inspector general, surgeon-in-chief, provost marshal general of freedmen, and chief quartermaster—had their headquarters in New Orleans. Throughout the state, subassistant commissioners oversaw assistant subassistant commissioners and local bureau agents, usually one in each parish. When the bureau reorganized its Louisiana bureaucracy in 1867, it replaced parish-level offices with regional ones at Baton Rouge, Franklin, Monroe, Natchitoches, New Orleans, Shreveport, and Vidalia. Often working thankless jobs with little potential for career advancement, most assistant commissioners for Louisiana served for only a few months; there were eight between 1865 and 1868. They counted among their ranks Baptist minister Thomas W. Conway, politico James S. Fullerton, war heroes Philip H. Sheridan and Joseph A. Mower, and career soldier Absalom Baird. High turnover was also common among subordinate bureau officers, which hindered the agency’s effectiveness.

The Freedmen’s Bureau suffered from poor funding. As planned, the agency took control of the confiscated and abandoned property of former Confederates and Confederate sympathizers for the purpose of supporting itself by selling or leasing these properties. In Louisiana, this land included the plantations and New Orleans residencies of Confederate Generals Braxton Bragg and Richard Taylor, Confederate foreign ministers Pierre A. Rost and Pierre Soule, and Confederate cabinet member Judah P. Benjamin, among other lesser-known people. As per the US Congress’ stipulations, bureau agents were empowered to lease or sell up to forty acres of this land to formerly enslaved people. Before the bureau could accomplish land redistribution, President Andrew Johnson ordered that the bureau restore all the lands in its possession to former Confederates, so long as they signed oaths of allegiance to the United States. (Johnson became president in April 1865 after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination.) By the end of 1865, the bureau had returned most of the 261 properties in its possession to former rebels, including over 62,000 acres of land leased to freed people; it returned another 85,600 acres the following year. By the fall of 1867, the Freedmen’s Bureau held only a handful of properties in New Orleans and two dozen plantations. With its only way of making money crippled, the bureau had to rely on special appropriations from Congress and on charging fees and taxes for its social and economic services.

Education

The Freedmen’s Bureau operated schools for formerly enslaved people and their children throughout the state. The Union army began many of these schools during its occupation of Louisiana. At its height in 1865, 230 white and Black teachers of both sexes taught basic skills in reading, writing, and math in 126 schools attended by 19,000 students, including 1,000 Black soldiers and 4,000 civilian adults. New Orleans was home to some of the largest schools, including the Frederick Douglass School in a former slave traders’ pen and the Abraham Lincoln School in the confiscated buildings of the University of Louisiana (predecessor to Tulane University). Freed people started many of the schools in rural places, and local bureau agents started others. Teachers were educated locals or northerners with philanthropic intentions; they were also often subject to violence and intimidation by white people antagonistic to educating Black people. At first, schools were free, but the bureau had no way to fund them. Its education system was often in financial crisis. Teachers went without pay, and school supplies were scarce. Attempts to charge tuition or tax laborers to support the schools resulted in resistance and decreased attendance. Freed people valued education, seeing it as key to their economic advancement, but few could afford to pay. By the beginning of 1867, the number of bureau schools had declined to 56, and there were only just over 2,500 students. With its education system falling apart, the bureau transferred control of its schools in New Orleans to the city government but maintained authority over education in rural areas. Education was one of the few bureau activities that continued past 1868 to the early 1870s, but the bureau’s involvement was limited to selling its schools to churches and Christian missionary organizations and providing small sums for those religious groups to start new schools.

Hospitals and Health Care

There were three bureau hospitals in Louisiana. In addition to treating the sick and injured, these hospitals were also places of refuge for elderly and disabled freed people and parentless children. Just as the bureau inherited its education system from the US Army, the bureau also inherited the army’s ad hoc health care system. This system existed because local white authorities refused freed people entry into public or private medical facilities. New Orleans was home to the largest bureau hospital in the state, located at the former Marine Hospital, a pre–Civil War institution established by the federal government for sailors. In addition to its medical mission, the New Orleans Freedmen’s Hospital also housed an orphan home for Black children. In 1866 the hospital admitted 2,000 patients, and the orphan home took in 110 children.

Hospitals also existed at the Rost Home Colony in St. Charles Parish and in Shreveport. Short-lived home colonies were part of the bureau’s health care mission, and the bureau stationed physicians at them. In response to temporary localized health care crises, the bureau transferred physicians around the state or hired locals. The bureau’s medical division suffered from the same lack of funding as its educational arm. At the end of 1866, the bureau employed just ten physicians; only the doctor in Shreveport worked outside southern Louisiana. The hospital at the Rost Home Colony closed in that year, and the hospital in Shreveport followed in spring 1868. Despite failed attempts to persuade local and state authorities to accept patients, the Freedmen’s Hospital in New Orleans closed in 1869 due to lack of funding.

Labor Regulation

Labor regulations and their enforcement comprised the most time-consuming duties of bureau officers. It was the bureau’s job to transition the southern economy from slavery to freedom, and regulating relations between laborers and employers—formerly enslaved people and their former enslavers—was crucial to achieving that goal. Bureau agents tried to balance the rights of freed people to sell their labor wherever and to whomever they wanted with the desires of plantation owners to gather laborers to perform seasonal agricultural tasks. Sometimes the bureau weighed in on the side of freed people, sometimes it backed plantation owners.

When employers presented contracts at the beginning of the year, bureau agents reviewed and explained them to freed people. Throughout the year, bureau agents investigated instances of violence and intimidation, common tactics plantation owners used to try to get freed people to work or to punish them for disobedience. The bureau also seized crops when freed people reported that employers failed to pay. Yet, it also oversaw contracts that restricted freed people’s movement to plantations for one year and constricted their freedom to work elsewhere during the contract period. Freedmen’s Bureau agents expelled freed people from plantations for refusing to work and captured and returned formerly enslaved people who left plantations during contract periods. Although bureau officials understood that former enslavers were keen to exploit and abuse freed people, they all too frequently subscribed to racist tropes of laziness themselves.

The Freedmen’s Bureau in Louisiana regulated labor another way: through its own tribunals, often called Freedmen’s Courts. The bureau created these courts as it recognized that civil governments in the South, controlled by former enslavers and Confederates, were unlikely to treat cases involving freed people with fairness and justice. Legally, the bureau was allowed to set up this alternative judicial system because Congress had yet to readmit Louisiana to the United States. Freedmen’s Courts heard cases involving crimes against Black people, and they allowed Black people to testify against white people. The bureau adjudicated everything from petty theft to civil rights abuses. Though local and state courts still heard the majority of cases, the bureau’s mere existence meant federal intervention in legal matters could come at any moment. When Congress readmitted Louisiana to the United States in 1868 after the state ratified the thirteenth and fourteenth amendments to the US Constitution, the bureau lost its power to adjudicate legal cases.

Opposition and Criticism

The Freedmen’s Bureau garnered criticism at every turn. Former enslavers and other white southerners resented the bureau’s support of freed people and their rights. Though they often couched their criticisms in terms of federal government overreach and corruption, racism motivated much of white opposition to the bureau. Locals intimidated and threatened teachers working for the Freedmen’s Bureau, and they burned schoolhouses for Black children. In 1866 white Louisianans murdered a bureau officer in Winn Parish. Opposition to the Freedmen’s Bureau and opposition to Black people’s rights went hand-in-hand.

Louisiana’s Black citizens, including formerly enslaved people and members of the antebellum free people of color, also had issues with the bureau. When the bureau sided with plantation owners to enforce the punitive clauses in labor contracts, Black people accused it of supporting coercive practices reminiscent of slavery. The bureau’s inability to support education or health care systems were ripe for criticism by those who most needed them. Some bureau officials could be just as racist and hostile to Black rights as former Confederates. When James S. Fullerton ran the bureau in the state, for instance, he refused to support universal male suffrage. Black critics felt that the bureau too often failed to fulfill its promises and live up to its expectations.

By the 1870s, there was little support in Congress to continue the bureau’s program. Acts of violence against Black people continued in Louisiana, including the Colfax Massacre in 1873 and the Battle of Liberty Place in 1874. The bureau’s retreat from Louisiana and other parts of the South in 1872 proved Reconstruction’s death knell.