Geodesic Domes

The geodesic dome was pioneered by architect Buckminster Fuller in the mid-twentieth century, and used in several notable Louisiana landmarks.

Courtesy of Louisiana Cultural Vistas Magazine

Geodesic Dome. Unknown

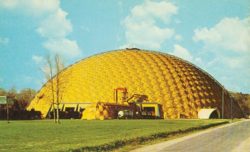

The geodesic dome is an unconventional architectural type pioneered in the mid-twentieth century by the legendary architect and inventor R. Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983). The design enjoyed limited but noteworthy appeal in Louisiana, most significantly in a prominent structure at the former Union Tank Car Company north of Baton Rouge. With a diameter of 384 feet, the Union Tank Car dome was the largest geodesic dome in the world at the time of its construction in 1958. The building eventually fell into disrepair and was demolished by a new owner in 2007, to the dismay of many.

Union Tank Car Dome

The Union Tank Car dome was designed by Fuller and his firm Synergetics, collaborating with the architectural and engineering firm of Battey and Childs. Rising to a height of 128 feet at its center, the structure was used as a repair and maintenance facility. The geodesic dome’s skin was composed of 321 identical hexagonal units of steel, each one-eighth of an inch thick and painted yellow. This skin was carried by an exoskeleton of blue-colored tubes, to which the folded-plate metal panels were anchored by tension wires. Only seven standardized parts—including plates, pipes, nuts, and bolts—were used in the dome’s construction. Attached to the dome was a long tunnel where the tank cars were taken to be repainted after being repaired within the dome. Together, the dome and the tunnel resembled a gigantic igloo.

This geodesic dome evolved from Fuller’s exploration into the geometry of circles and tetrahedrons, and into the creation of economical multipurpose structures. Fuller adopted the word geodesic—from the Greek “geo” (earth) and “daiesthai” (to divide)—to describe his creation.

In the 1950s, the Union Tank Car Company was a leading supplier of tank cars serving the petrochemical industry in southern Louisiana and elsewhere. The company chose the dome because it promised a more efficient means of repairing the tank cars than had the customary system of linear tracks within a rectangular building. In such a system, cars that needed only minor repairs got trapped in line by those requiring more attention. The dome resolved that problem: rail tracks carried the tank cars directly into the dome through an opening next to the paint tunnel, where they were placed on a massive circular transfer table and rotated to one of thirty repair slots. As well as providing smooth processing lines, the dome offered many other advantages. For example, there were no interior supports to get in the way of work, and the dome’s shape allowed for a central point from which repairs could be visually monitored. Illuminating the entire interior was a “wheel” fitted with mercury vapor lamps and suspended thirty-four feet above the work areas.

Union Tank Car considered the structure such a success that it built two more in other states. The Baton Rouge dome—known locally as “the Bucky Dome”—was widely publicized, even getting featured in Fortune magazine. The 2010 documentary film A Necessary Ruin recounts the creation and use of the dome as well as its demolition by Kansas City Southern Railway after it bought the facility.

Fuller was born in Massachusetts in 1895 and died in Los Angeles in 1983. Sometimes described as a futurist, Fuller—or “Bucky” as he was commonly known—was a utopian designer who incorporated his knowledge of engineering, mathematics, environmental science, architecture, and, not least, philosophy into his inventions and designs. He was brilliant at publicizing his projects and himself through his writings (he wrote more than twenty books, including poetry), teaching, and presentations.

Gold Dome of Centenary College

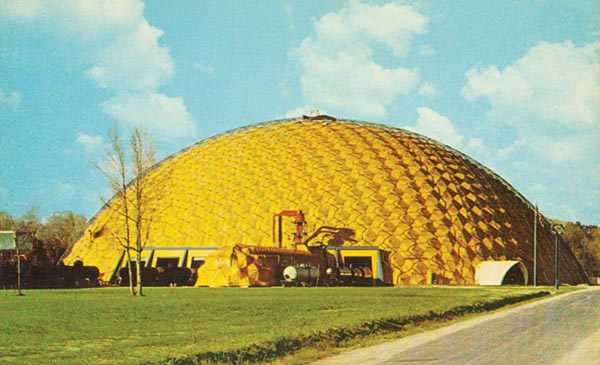

The largest remaining geodesic dome in Louisiana is the Gold Dome on the Centenary College campus in Shreveport. It has a diameter of 195 feet and rises 82 feet at the center. The five-sided structure varies somewhat from Fuller’s original concepts but is an outgrowth of his geodesic geometry. It is constructed of aluminum diamond-shaped panels with a tubular aluminum strut. Unlike the Union Tank Car dome, however, the Gold Dome does not extend to the ground but sits on a brick base. This platform serves the building’s function better, for it was planned to contain a basketball arena with a seating capacity of about three thousand people and to include classrooms and offices. The Gold Dome was designed by the Shreveport architectural firm of Somdal, Smitherman, Sorenson, Sherman, and Associates; it opened in 1971.

The Gold Dome was one of several geodesic domes that drew on Buckminster Fuller’s prototype. Fuller himself had designed a geodesic domed roof for the Ford Motor Company Rotunda in Dearborn, Michigan, in 1953 and a geodesic dome for the American pavilion for a trade fair in Kabul, Afghanistan, in 1956. He went on to create a geodesic dome as the United States pavilion for the Expo 67 World’s Fair in Montreal in 1967; that structure is now the Biosphere, which showcases water ecosystems, a purpose that would have pleased Fuller. Spaceship Earth, an eighteen-story sphere housing a time-machine-themed ride at Walt Disney World’s Epcot Center in Florida, was built in 1982 and based on Fuller’s scheme.

R. Buckminster Fuller’s Legacy

In 1960 Fuller designed a geodesic dome house where he lived with his wife until 1971. The dome was built of plywood, and it leaked, as did many of the early geodesic domes until precision in parts manufacturing helped cure that problem. There was a small flurry of interest in geodesic dome houses in the 1960s—a handful were built in Louisiana in that period—but the type never achieved widespread popularity. The form or a variant of the form, however, did become somewhat popular in the 1960s for such demountables as cardboard furniture and light shades.

According to Fuller, his first octet truss was constructed of dried peas and toothpicks when he was in kindergarten. He went on to spend his life experimenting with building forms. In 1929 he developed a housing prototype that he named Dymaxion, made up from the words “dynamic,” “maximum,” and “ion.” This lightweight hexagonal house, hung from a column and secured by cables, was powered by solar energy. In 1933 Fuller reused the term for the three-wheeled, bullet-shaped car that he built. The car was based on lightweight aircraft technology in order to be fuel efficient. In 2010 famed British architect Norman Foster, an acquaintance of Fuller’s, had a version built to add to his car collection.

Fuller’s ideas were disseminated in his many writings and public presentations. He served as a visiting lecturer in architecture departments at universities throughout the country, including the University of Louisiana at Lafayette and Tulane University in New Orleans, where he worked with students to build models of geodesic domes. Fuller lived and experimented in an era of intense interest in the potential fusion of science and art to create a more perfect world. The geodesic dome was—and is—a manifestation of that optimism.