Germantown Utopian Colony

Germantown was a utopian colony founded in 1835 by a breakaway sect of the Harmony Society in what is today rural Webster Parish near the town of Minden.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

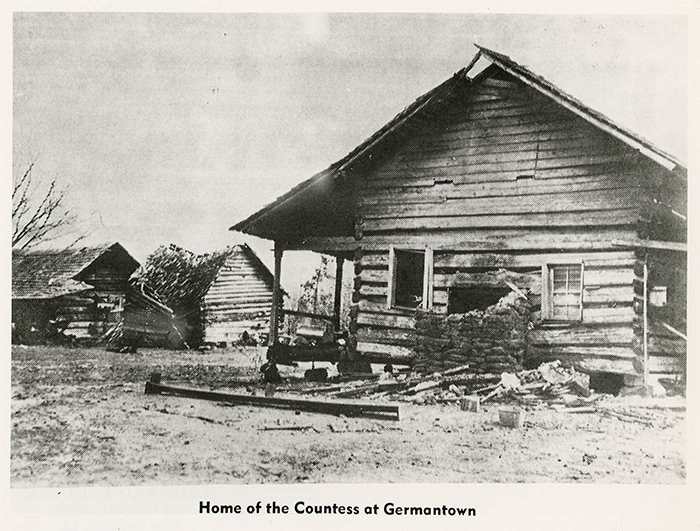

The northwestern Louisiana site that became home to the utopian "Philadelphian Society" was named Germantown. This cabin, photographed in ruins sometime between 1950 and 1973, was home to one of the colony's leaders.

Germantown was a utopian colony founded in 1835 by a breakaway sect of the Harmony Society in what is today rural Webster Parish near the town of Minden. For nearly four decades the religious hamlet operated on a communal basis led by the widow of an idealistic visionary named Bernhard Müller, the self-proclaimed “Count de Leon” and “Lion of Judah,” who died of yellow fever while leading his followers to their Louisiana settlement. At its peak, the colony was known for its cultivation of the arts. Only a few remaining log structures and the Germantown cemetery have been restored and opened to the public as a museum operated by the office of the Louisiana Secretary of State.

Germantown’s Precursors

The Harmony Society emerged in southwestern Germany during the late eighteenth century, as European scientists, philosophers, and theologians were questioning the social structures of their day—political, economic, and religious. George Rapp, a journeyman weaver inspired by Christian mystics and Pietists, developed his Millennial sect, the Harmony Society, which separated from the Lutheran Church in 1785. By the 1790s Rapp had attracted more than ten thousand followers who refused to serve in the military or send their children to Lutheran schools. When the government began to persecute the Harmonists for their nonconforming views, Rapp decided the group must emigrate.

The Harmonists founded several settlements during the first half of the nineteenth century in the United States, where they intended to practice their utopian ideals to prepare for the Second Coming of Christ, which they believed to be imminent. Rapp and around 500 of his followers came to the United States in 1804, where they established their first community called Harmony in Butler County, Pennsylvania. After a decade, their land could no longer sustain the population, which had grown to 800, so the Rappites relocated to southern Indiana where they founded a second Harmony settlement in 1814. Rapp and his followers remained at this site until 1825, when the Scottish idealist Robert Owen bought the town. Owen renamed the Indiana settlement New Harmony and shifted the emphasis of the communal living system from religious ideology to literary and cultural pursuits, but Owen’s society went out of existence in the 1850s. Meanwhile, the Harmonists returned to Pennsylvania and established a new community called Economy north of Pittsburgh. Rapp’s colony flourished for a few years but also fell to internal squabbles before the Civil War.

In 1831, another radical religious visionary arrived with forty followers in the Economy colony. He used several names and titles throughout his life, including Bernhard Müller, Maximilian Bernhard Ludwig, and the Archduke Maximilian von Este. Like Rapp, Müller was born in Germany; he practiced alchemy and, adopting the name “Proli,” claimed to be the Messiah. As the uncle of Empress Marie Louise of Austria, Napoleon’s second wife, he had ties to royalty throughout Europe and used these connections to accumulate wealth and to remain in Europe long after authorities had expelled most other utopians. By the time of his departure for America, “Proli” was calling himself the “Lion of Judah” and inventing the title of “Count de Leon.” Among his followers, he had attracted prominent and learned people such as Dr. George Goentgen, the chief librarian of Frankfurt. The group called itself the Philadelphian Society, and its doctrine was based on an intricate system of tenets revealed by its leader, who claimed a new world order would replace the existing society, signaling the beginning of the Millennium referred to in the Bible. To prepare for the new era, of which Count Leon would be the leader, believers were to organize themselves into communal settlements, sharing all goods in common while awaiting the return of the Lord and the start of the Millennium. Followers believed that God had revealed to Leon that Christ would return first to North America and establish the true Christian church there because of the United States’s freedom of religion.

Leon contacted Rapp in Pennsylvania, expressed his views to the older leader, and asked to join the colony. Many of the Count’s ideas coincided with Rapp’s, so he welcomed Leon’s group to Economy. Soon after the Philadelphian Society arrived, Leon’s charisma attracted a following among the community residents that rivaled Rapp’s, and a civil war erupted in the colony. The battle spilled over into the courts and led to a separation. Leon and his followers, who now numbered almost a third of the community, left Economy with a court award of $105,000 and established Phillipsburg on the Ohio River north of Pittsburgh in 1832. This group, called the New Philadelphia Congregation, built many impressive brick buildings at the site, which is today the town of Monaca, Pennsylvania. Problems arose at Phillipsburg, largely because Leon’s faith in his religious tenets was stronger than his grasp of financial realities. Under the threat of additional lawsuits from the Harmonists, Leon led his followers on another exodus, westward and to the south, to the latitude of Jerusalem.

Emigration to Louisiana

In September 1833 Leon and his congregation started down the Ohio River; five months later, the party landed at Grand Ecore, Louisiana, on the Red River. This first Louisiana site, while closer to Biblical latitudes, was unhealthy. An epidemic of yellow fever broke out, claiming many members of the settlement—most notably Count Leon who died on August 29, 1834. His death, ironically, probably extended the colony’s life. The remaining settlers attempted to stay at the Grand Ecore site, which they renamed Gethsemane. However, the unhealthy conditions, combined with flooding that destroyed much of the settlement, including its cemetery, forced them to relocate.

In 1835 the colonists moved north to Claiborne Parish and bought a tract of hilly land much like their home territory in Germany. This final home of the colony lies a few miles north of present-day Minden, which was founded later, in 1836 or 1837, by Charles Veeder of New York, whose family background was German. Some historical evidence indicates Veeder met the Germantown settlers in Kentucky as they headed down the Ohio River. Such contact might have influenced his choice of a site for a town, since he arrived with a steamboat load of goods for sale, suggesting that he might have known settlers were already in the area.

At Germantown, freed from the control of the overly idealistic Leon, the colony began to prosper. The widowed Countess Leon, Goentgen, and business manager John Bopp assumed leadership of the colony. While the colonists were still bound by their earlier pledges to follow the religious teachings of Count Leon, the day-to-day operation of the settlement took on a more practical edge and became very successful. The residents planted cotton, and the leaders carried out fairly extensive real estate deals. A community store became the center of the life of the colony, and the communal experiment continued. The town featured five houses besides the bachelors’ quarters. (One of Leon’s tenets forbade marriage until the return of Christ; this teaching was later ignored.) Other buildings included the store, a community kitchen, a school—presided over first by Goentgen and later by William Stakowsky—work sheds, and outbuildings. The colony had its own shoemaker, tinsmith, smokehouse, cotton gin, sawmill, carpentry shop, blacksmith, and saloon. Settlers planted fruit orchards and grew mulberry trees, feeding the leaves to silkworms that produced thread for cloth. The community raised sheep, cattle, chickens, geese, and other livestock. The colony was a self-sufficient island that exported its products to the nearby community of Minden, including peach brandy made from the fruit of the commune’s orchards.

Germantown’s Legacy

Perhaps Germantown’s most significant export to its neighbors was culture. Community members were educated and trained in all areas of the arts. Goentgen had an impressive library that unfortunately was lost after the colony folded. The countess, a trained musician, created beautifully handwritten musical scores to avoid the cost of printed music. She designed a practice board called a digitorium that she used to teach piano to her students before the colony could get a real instrument. After a piano was obtained, she taught many young women in Minden to play. Later, Stakowsky began traveling to town on a regular schedule to teach music lessons as well, bringing Old World culture to the frontier outpost.

Germantown continued to prosper into the 1850s, maintaining its communal practices: each member had a specified role and each shared in the fruits of the colony’s efforts. During these years, a new settler, Dr. F. O. Krouse, arrived and assisted Bopp with business management. The economic stability of the colony for all these years is one of its outstanding qualities.

In 1861 the Civil War broke out, and the conflict that split the nation also proved to be the death of Germantown. The community never owned slaves and took no official side during the war, but the colony welcomed deserters and fugitives from the Confederate army, and some of Germantown’s most prominent members, including Krouse, joined the rebel forces. The differences that began at this time only widened as war continued. When the conflict ended, the economy of the South was ruined, bringing an end to this experiment in communal living. In 1871, a financial settlement was made among the members, and the colony formally disbanded. Most members remained in the area and set up individual homesteads. The land where the colony sat became the home of the Krouse family. Descendants of the Krouses and other Germantown families still populate the area.

Many artifacts of the original settlement were scattered among the descendants or allowed to suffer the erosions of nature. In the struggle to survive the hardships of everyday life, the community largely forgot its unique heritage. The colony’s buildings fell into disrepair. Goentgen’s library and the valuable furnishings and artwork he and the countess owned disappeared or were destroyed. Fortunately, during the first half of the twentieth century, the colony came to the attention of two individuals who saved Germantown from near oblivion. Dr. Karl Arndt, a professor of German language at Louisiana State University, began doing work at the colony site in the late 1930s. Although he later shifted his work to the entire Harmonist movement and Rapp in particular, Arndt established the role of Germantown as a historical equal to the settlements at Harmony and Economy. Later, Rita Moore Krouse spent years painstakingly researching the colony after marrying into the Krouse family in the 1940s. As a result, the Germantown Colony Museum was established in 1975 on the site of the original settlement and features some surviving buildings of the colony and reconstructions of others. The site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979, and the state of Louisiana assumed control of the museum in 2009.