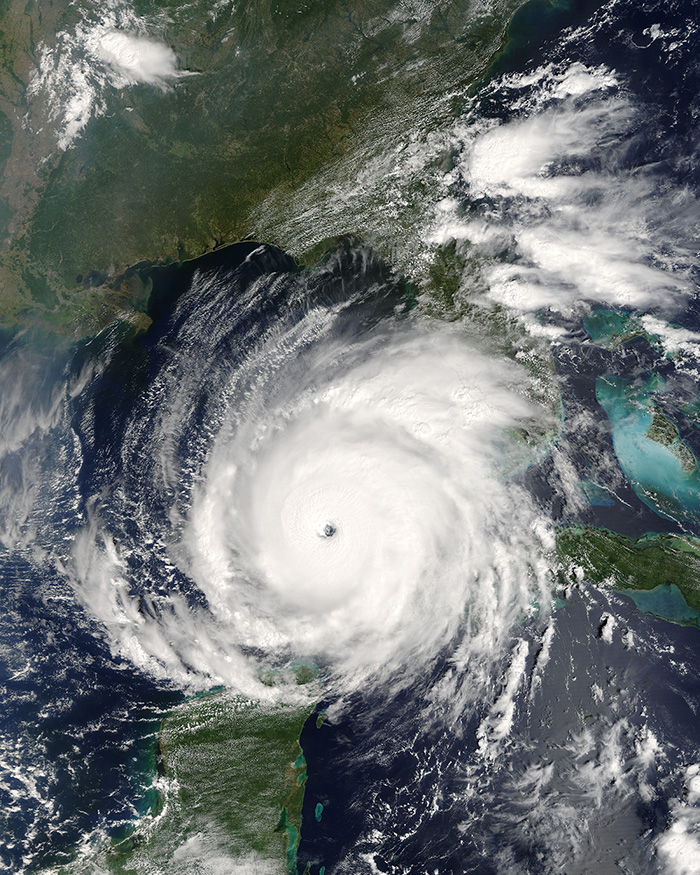

Hurricane Rita

Making landfall in Cameron Parish on September 24, 2005, Hurricane Rita was the fourth-most-intense Atlantic hurricane ever recorded.

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Satellite View of Hurricane Rita. Jacques Descloitres

The widespread destruction that Hurricane Katrina inflicted on New Orleans and the Mississippi Gulf Coast in August 2005 attracted worldwide attention, but Katrina was not the only major hurricane to cause extreme damage to Louisiana that year. Just twenty-six days after Katrina’s landfall, Hurricane Rita—the fourth-strongest Atlantic hurricane ever recorded—swept from east to west across the upper Gulf of Mexico and flooded communities across 250 miles of coastal Louisiana.

Rita’s tremendous storm surge washed away or otherwise destroyed most homes and businesses in lower Cameron Parish, and residents of such communities as Grand Chenier, Creole, Cameron, Holly Beach, and Johnson’s Bayou were displaced for months. Several communities across Vermilion Parish and along the many bayous extending south from Houma in Terrebonne Parish, including the Native American settlement at Dulac, also bore the brunt of Rita’s wrath. In the years that followed, residents would complain of “Rita amnesia” on the part of government agencies and the national media, which paid scant attention to their plight while attending to and covering the rebuilding of New Orleans after Katrina. Recovery efforts also were punctuated by controversial suggestions by some government officials and planning consultants—which were vigorously opposed by local residents and Cajun culture champions—that smaller communities be abandoned and their occupants relocated away from the coastal flood zone.

2005: A Record-Breaking Hurricane Season

The 2005 hurricane season was a remarkable one, unprecedented in both quantity and ferocity. Twenty-seven tropical storms and hurricanes formed in the North Atlantic Basin that year—so many that the World Meteorological Organization ran out of names and had to use letters of the Greek alphabet to identify the last six. By the time Hurricane Zeta played out—on January 6, 2006, more than a month after the supposed end of the 2005 storm season—the Gulf region had endured seven major hurricanes, with death and destruction extending from Florida to Texas. In the midst of that turmoil, storm No. 17—Hurricane Rita—became, for a time, the largest hurricane ever measured within the Gulf of Mexico. It was one of the strongest Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes ever recorded, and a crew of “hurricane hunters” from the Air Force Reserve measured one of its wind gusts at a remarkable 235 mph. When it appeared to be heading toward Houston, Texas, the fourth-largest city in the United States, it spawned the largest evacuation in American history.

Rita made landfall on September 24 at the western edge of Cameron Parish, near the Texas border, as a large Category 3 hurricane. It was so strong that it knocked out most of the weather buoys in its path before it reached shore; it also destroyed most of the homes and other buildings along the coast road, Louisiana 82. With no high-water marks to study, no eyewitness accounts due to a thorough evacuation, and little data recorded by weather gauges before they became disabled, the National Hurricane Center could only make an educated guess at Rita’s precise characteristics at time of landfall: sustained winds of 120 mph, with massive waves atop a fifteen-foot storm surge. Across Cameron Parish, raging floodwaters swept houses and their contents into the parish’s vast marshes and dislodged almost 350 coffins from cemetery burial plots and mausoleums. “I would use the word ‘destroyed,’” Army Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré, commander of US military relief operations in Louisiana, said of Cameron and Creole after his initial tour of southwestern Louisiana following Rita’s landfall. “Most of the houses and public buildings no longer exist.”

Vast Devastation

The surge pushed thirty miles inland via the Calcasieu River and flooded downtown Lake Charles, destroying a dockside casino and badly damaging the lakefront civic center. The city’s airport terminal was wrecked by a tornado, and houses in many parts of the city lost roofs to the hurricane-force winds or were damaged by fallen trees. To the east in Vermilion Parish, small towns such as Delcambre, Erath, and Henry were inundated, as were sugarcane farms, rice fields, and cattle ranches. The hurricane hit just weeks before the annual sugarcane harvest, and the usual wind damage to mature cane stalks was accompanied in lower Vermilion Parish by tons of debris that washed into the cane fields on the storm surge. The flooding was particularly disruptive for the area’s rice farmers because salt water that overtopped levees surrounding the rice fields could not escape when the storm tide receded. In many cases, fields were ruined for one, two, or more growing seasons because salt from the trapped gulf water seeped into the soil at toxic levels before farmers could arrive with heavy equipment to break their levees and release the floodwaters.

By churning along the entire length of Louisiana’s southern coast and flooding communities as it went, Rita left a massive swath of destruction in its wake. In the months and years of recovery that followed, though, residents became frustrated by the lack of attention paid to their plight in the shadow of post-Katrina New Orleans. That disparity had several causes. New Orleans is a major, international city with historical significance; the region hit by Rita was less familiar by comparison. Katrina killed 1,577 people from Louisiana; only one person died in Rita. The flawed government response to the Katrina tragedy in New Orleans became part of that storm’s narrative; although the Rita damage was extensive, it was spread out among many smaller, isolated communities, making the impact harder for outsiders to assess. In time, the Federal Emergency Management Agency funneled many millions of dollars into the coastal parishes—the base of Louisiana’s Acadiana triangle—to repair vital infrastructure and to rebuild schools and other public buildings destroyed by Rita, and the Road Home program set up by the state government helped homeowners restore their storm-ravaged houses. In many cases, though, the relief came with a caveat that homeowners had to make their houses more flood-resistant by elevating them to new minimum height standards dictated by the National Flood Insurance Program. For many people who wished to return, the financial burden of that new regulation added to the challenge of rebuilding, so after Rita and follow-up flooding from Hurricane Ike in 2008, many residents voluntarily relocated to inland communities. As a result, the population of Cameron Parish was estimated by the US Census Bureau in 2012 to be 33 percent less than its pre-Rita population.