L’Union

The South’s first Black newspaper, L’Union was an abolitionist journal that promoted full citizenship rights for men of African descent.

Courtesy of Roudanez History & Legacy

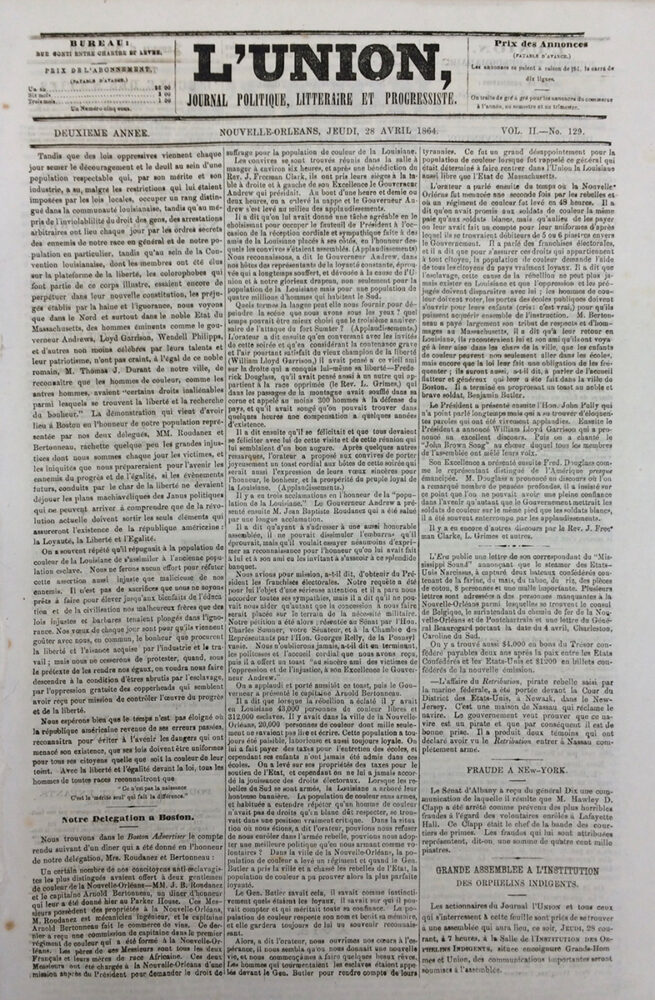

L'Union Newspaper, 1864. L'Union

The South’s first Black newspaper, L’Union was founded by free men of color Louis Charles Roudanez, Jean Baptiste Roudanez, and Paul Trévigne. The staunchly abolitionist journal ran from 1862 to 1864 and promoted full citizenship rights for men of African descent. It also focused on voting rights, issues confronting the Black military, white prejudice, Louisiana politics, federal policy, and Civil War news.

L’Union debuted on September 27, 1862, five months after Union forces captured New Orleans from the Confederacy. The paper first appeared as a two-page, bi-weekly French-language publication, becoming a tri-weekly later that year. A few issues appeared in French and English, and occasionally the paper expanded to four pages. Initially published on the corner of Chartres and St. Louis Streets, L’Union moved its office to 21 Conti Street (now 527 Conti) in April 1864.

L’Union was primarily read by francophone free people of color residing in the French Quarter and the Faubourgs Tremé and Marigny. This racially mixed, well-educated, prosperous, and politically assertive community was one of the largest of its kind in the United States.

L’Union’s first edition summoned readers to rally around a new crusade that called for racial justice: “We inaugurate today a new era in the South … You who want to establish true republicanism, democracy without shackles, gather around us.” L’Union writers often framed their mission within a framework of larger revolutionary forces, believing they were on the cusp of a new era. “Mankind is still marching. And, in spite of the conservatives, great progressive principles will emerge from the shockwave of liberal ideas rocking the two worlds today in their glorious births. March. Live. It is your right. And it is more, it is your duty.” The editorial “Aux Armes!” (“To Arms!”) proclaimed: “We demand justice. And when an organized, numerous, and respectable body which has rendered many services to the nation demands justice—nothing more, but nothing less—the nation cannot refuse.”

L’Union initially advocated for the civil rights of free people of color, reasoning that “the old free colored population” was worthy of citizenship by virtue of “their past conduct and by the degree of civilization which they have reached.” As time passed the paper advocated for all men of African descent. To that end L’Union publisher Jean Baptiste Roudanez and fellow delegate Arnold Bertonneau delivered a petition to President Lincoln on March 12, 1864, demanding the right to vote, including “the extension of the right of suffrage to those born slaves.” Reaffirming this position L’Union argued that “all not born free within the state [must] be immediately enfranchised by the abolition of slavery …” Editor Paul Trévigne urged racial solidarity, calling for the “harmony among all descendants of the African race … United we stand! Divided we fall!”

Free Black people rallied around L’Union, but the newspaper faced many challenges, including threats of violence, loss of financial support, and a small readership base. Its last issue appeared on July 19, 1864. Embracing a bold new strategy, the men of L’Union hoped to end the old divisions between free people of color and the enslaved. To that end, the New Orleans Tribune launched out of the same office on July 21, 1864. Published in French and English, the Tribune reached a much larger audience, emphasizing issues of central importance to all people of African descent.