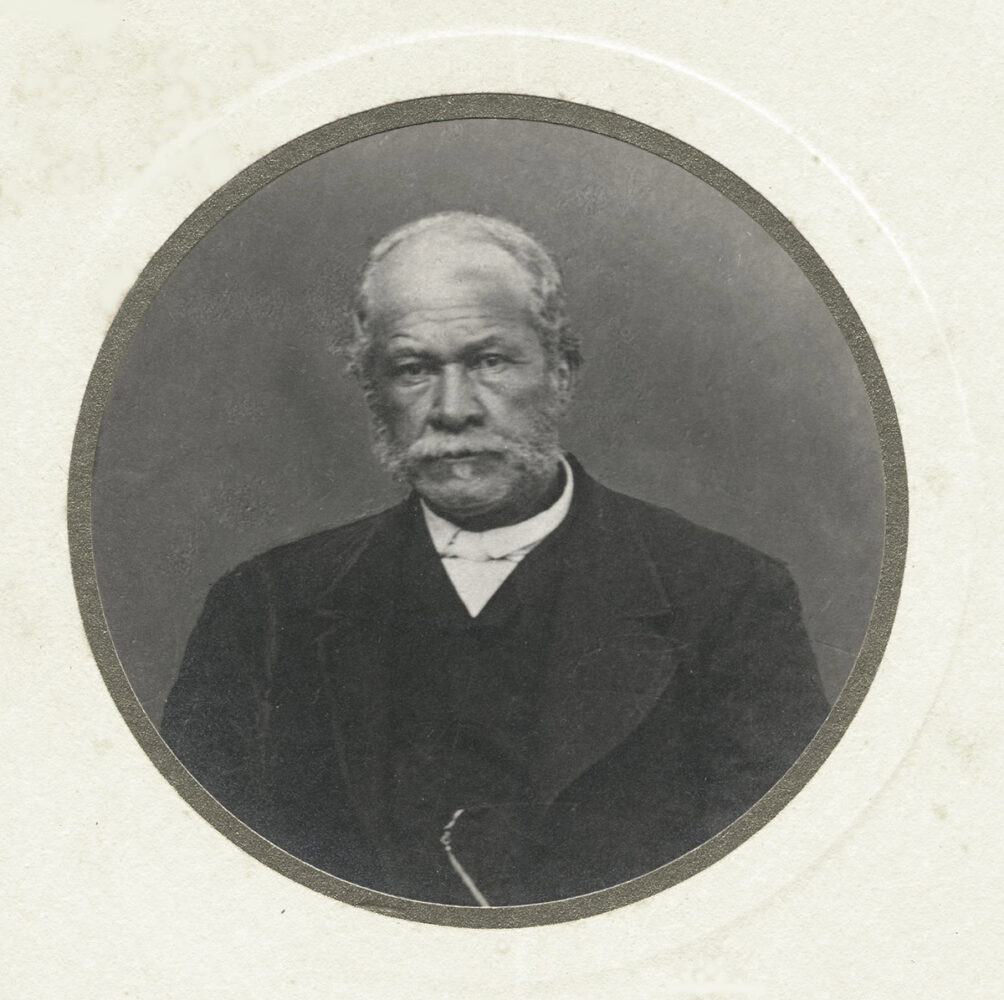

Louis Charles Roudanez

Founder of L’Union, the South’s first Black-owned newspaper, as well as the New Orleans Tribune, America’s first Black daily, Louis Charles Roudanez was a staunch abolitionist and advocate for the liberation of all Black people.

Roudanez History & Legacy

Louis Charles Roudanez, ca. 1889.

Louis Charles Roudanez was a visionary free man of color and journalist. He founded L’Union (1862–1864), the South’s first Black-owned newspaper, and the New Orleans Tribune (1864–1869), America’s first Black daily newspaper. According to historian John Blassingame, in addition to his journalistic and political endeavors, “Roudanez was one of the best trained physicians in New Orleans and had a lucrative practice among Blacks and whites in the city.”

Roudanez was born in 1823 in Saint James Parish to Aimée Potens, a free woman of color, and Louis Roudanez, a white refugee from the French colony of Saint-Domingue. He was raised in New Orleans and eventually earned a degree from the Faculté de Médicine de Paris in 1853. While a student in France, Roudanez was influenced by French republicanism and participated in the 1848 revolution. He earned a second medical degree from Dartmouth College in 1856. Roudanez returned to New Orleans in 1857 and established his medical office in the French Quarter. He married Célie Saulay, a free woman of color with whom he had ten children.

When Union forces seized New Orleans in the spring of 1862, Roudanez quickly aligned with free men of color to advocate for their civil rights. On September 27, 1862, Roudanez, his brother Jean Baptiste Roudanez, and Paul Trévigne launched L’Union, the South’s first Black newspaper. The tri-weekly French-language newspaper was staunchly abolitionist and campaigned for full citizenship rights for men of African descent. Disheartened by a lack of progress, financial setbacks, and threats of violence, L’Union folded on July 19, 1864.

On July 21, 1864, Roudanez debuted a decidedly more radical journal. The New Orleans Tribune became America’s first Black daily newspaper on October 4, 1864. Roudanez was the Tribune’s principal financier and guiding spirit. Editor Jean Charles Houzeau said Roudanez “steadfastly demanded and claimed his rights to their fullest extent with a strength of soul that I always admired.”

Identifying as the “organ of the oppressed,” the Tribune defiantly promised to “spare no means at our command” to press for the liberation of all Black people. The paper advocated for full citizenship rights, especially universal manhood suffrage. Devised as an organizing tool, the Tribune rallied a progressive movement and eventually succeeded in achieving many of its civil rights goals, including the right to vote and integrated public schools.

Angered by the nomination of Henry Warmoth as the Republican candidate for Louisiana governor, Roudanez bolted from the party. Consequently, the Tribune lost institutional and

financial support, resulting in the newspaper’s demise in 1868. Roudanez largely withdrew from the spotlight thereafter.

He briefly participated in the Reunification Movement of 1873, a short-lived effort to build a progressive political coalition of Black and white people calling for racial equity during Reconstruction. When Reconstruction ended and white supremacist violence mounted, Roudanez brought his wife and many of his children to the relative safety of Paris. Returning to New Orleans in 1879, he concentrated on his medical practice. Roudanez died in New Orleans on March 11, 1890, and is buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. Paul Trévigne wrote the doctor’s obituary, declaring “Roudanez will be added to the galaxy of the brilliant constellation of Louisianans who have, here and abroad, honored their State and their race by their talents and their worth.”