Napoleonic Code (French Civil Code)

France’s Civil Code of 1804 standardized civil law and became a model legal framework around the world, including in Louisiana.

This entry is 6th Grade level View Full Entry

The Historic New Orleans Collection

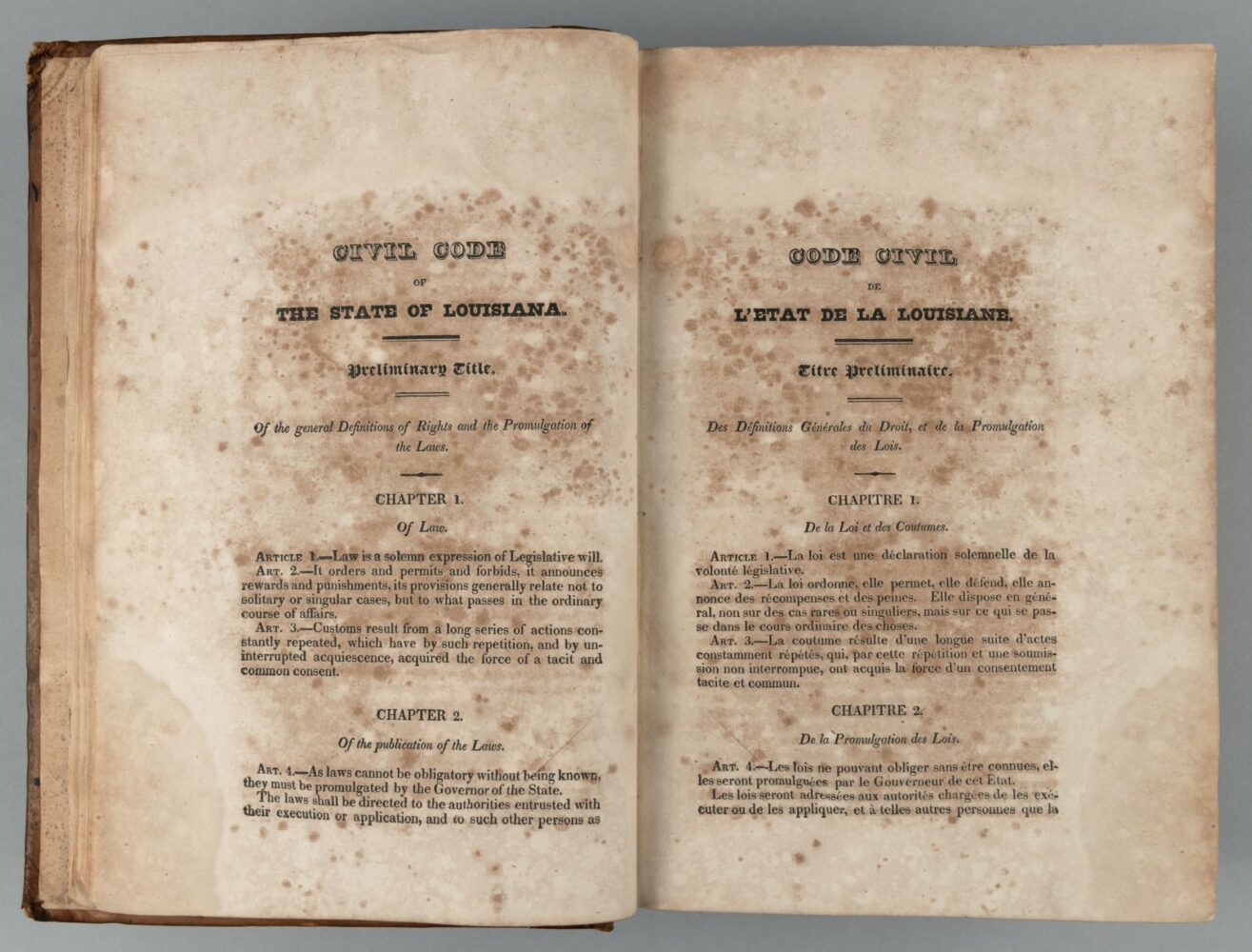

An interior spread from the Civil Code of the State of Louisiana, featuring an English translation on one page and French on the opposite page.

In modern times, the Napoleonic Code, or the French Civil Code, has been the foundation for French private law. At the time of its enactment, it was a product of a revolutionary and nationalist spirit in France shaped by an Enlightenment belief that rules and principles could be rationally derived and outlined. The Napoleonic Code is a blend of revolutionary innovation and customary law that ruled large parts of France in the early nineteenth century. It also draws upon written Roman law that was common throughout large parts of Europe at the time. This code of laws covers a range of legal interactions between private citizens, including property, contracts, sales, leases, and wills. In addition, the Napoleonic Code has served as a model for private law as far away as Africa, Asia, South America, and Europe. Louisiana is the only state in the United States whose system of laws is based on the Napoleonic Code rather than English common law.

How and why was the Napoleonic Code developed?

After the French Revolution in 1789, France’s existing laws required revision. The revolutionary causes of liberté, égalité, fraternité—liberty, equality, fraternity—were incompatible with laws from earlier times. Before the revolution, there wasn’t a single legal framework in France. Different laws applied in different areas, and not all laws were written down, which made fair application of the law challenging. The existing laws also gave preference to wealthy people, like aristocrats and the nobility. As a result of the revolution, a new, unified legal framework—one that was written down and applied equally to all people—was necessary.

The Napoleonic Code was heavily influenced by Enlightenment ideas that also influenced the revolution. Although it wasn’t the first civil code, the Napoleonic Code was the most influential. There had been earlier codification attempts in Austria and Prussia in the mid-to-late 1700s. Codification efforts had even been attempted in France before the Napoleonic Code, but the task was finally accomplished through the influence of Napoleon Bonaparte, who claimed power over the French government in 1799 and made himself emperor of France in 1804. The civil code was enacted, at least in part, because of his strong will and political skill. In 1800 Napoleon appointed a team of four experienced legal practitioners to rethink French law. They created a draft of the civil code in just four months.

Between 1801 and 1803 Napoleon helped push through the newly drafted code, and its laws were enacted into thirty-six separate statutes, or formal written laws enacted by the legislature. The next year, on March 21, 1804, the individual statutes were consolidated into a single code. In 1807 it was officially renamed the Code Napoléon, or Napoleonic Code, to recognize Napoleon’s role in passing it. (The French changed the name in 1816 to remove Napoleon’s name, but when Napoleon’s nephew Napoleon III came to power, he changed the name back in 1852.) Since 1870, however, it has been referred to simply as the Code Civil, or French Civil Code.

What kinds of laws did the code contain, and how were they applied?

The French Civil Code includes 2,281 articles broken into three separate sections or “books.” Book I outlines the rights of people, Book II addresses property law, and Book III deals with rights that people have in things, including rights acquired by contracts, sales, successions (inheritances), and other methods.

Book I includes regulations on the basic institutions of what was considered “civilized” society, including marriage, guardianship, tutorship, and the family. Despite the revolutionary spirit that in part motivated codification, family laws laid out in Book I were largely traditional. Although the revolution generally recognized women as equal to men, the father remained the head of the family. Divorce was recognized, but not easily permitted. Divorce was allowed if someone had committed adultery or cruel treatment, but the easier-to-obtain approach—of divorce by mutual consent of both husband and wife as had been practiced during the revolution—was gone.

Property law in Book II follows more revolutionary principles. According to André Tunc, property ownership was defined as “a complete, absolute, free, and simple right”; its key provision was an individual and absolute right to property for all, no matter whether people were rich or poor or if they came from the upper or lower classes.

In Book III, which has been called a “grab bag” of different types of legal transactions, some important changes were made regarding torts and special and general contracts. (A tort is a civil wrong committed against someone that requires the person who committed the wrong to pay compensation to the injured. A modern-day example is a car accident, where the person at fault is responsible for paying for the damage. An example of a special contract is a lease.) After the revolution, this area of law stayed mostly the same. However, other areas of contract law, such as the law of sales, are heavily influenced by Roman tradition, meaning these laws weren’t inspired by revolutionary thinking but rather drew on much older traditions. The drafters also changed how successions, donations, and wills are handled by rejecting old ideas about first-born children and male heirs. In Book III, the drafters balanced the idea of individual freedom with family unity and the obligation to leave property to heirs after death.

What were the long-term effects of the code?

Through export or conquest, the Napoleonic Code was adopted by a variety of European jurisdictions, including Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Italy, and various Germanic territories. In the early twentieth century, the code became a model for jurisdictions, including countries, territories, provinces, and states, codifying their own laws. These include countries in Europe, Latin America, North Africa, and the Middle East.

Lastly, the Napoleonic Code influenced law in two former French colonies, Québec and Louisiana. Louisiana is the only jurisdiction in the United States with a civil law system, and it is naturally connected to French civil law. First a French colony from 1699 to 1762, and then again from 1800 to 1803, Louisiana’s first codification occurred in 1808, only four years after France first enacted the Napoleonic Code. It is still debated whether the Louisiana Digest of 1808 drew primarily from Spanish or French law, but when Louisiana revised its civil code in 1825, French sources, had a significant influence. The Louisiana courts continue to consult the French Civil Code and related sources when determining the meaning of various provisions in the Louisiana Civil Code today. For example, when the courts find that a provision of the Louisiana Civil Code is unclear, judges and lawyers consult the French Civil Code because it is the source of Louisiana law. Consultation of the French Civil Code applies only in Louisiana, as it is the only state in the country whose laws are based on French, rather than English, law. Outside of Louisiana, states rely on English common law, which is based on legal precedents established by the court system.