Natchez Indians

The Natchez are an American Indian group that lived along the Lower Mississippi River during the rise of European colonialism.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

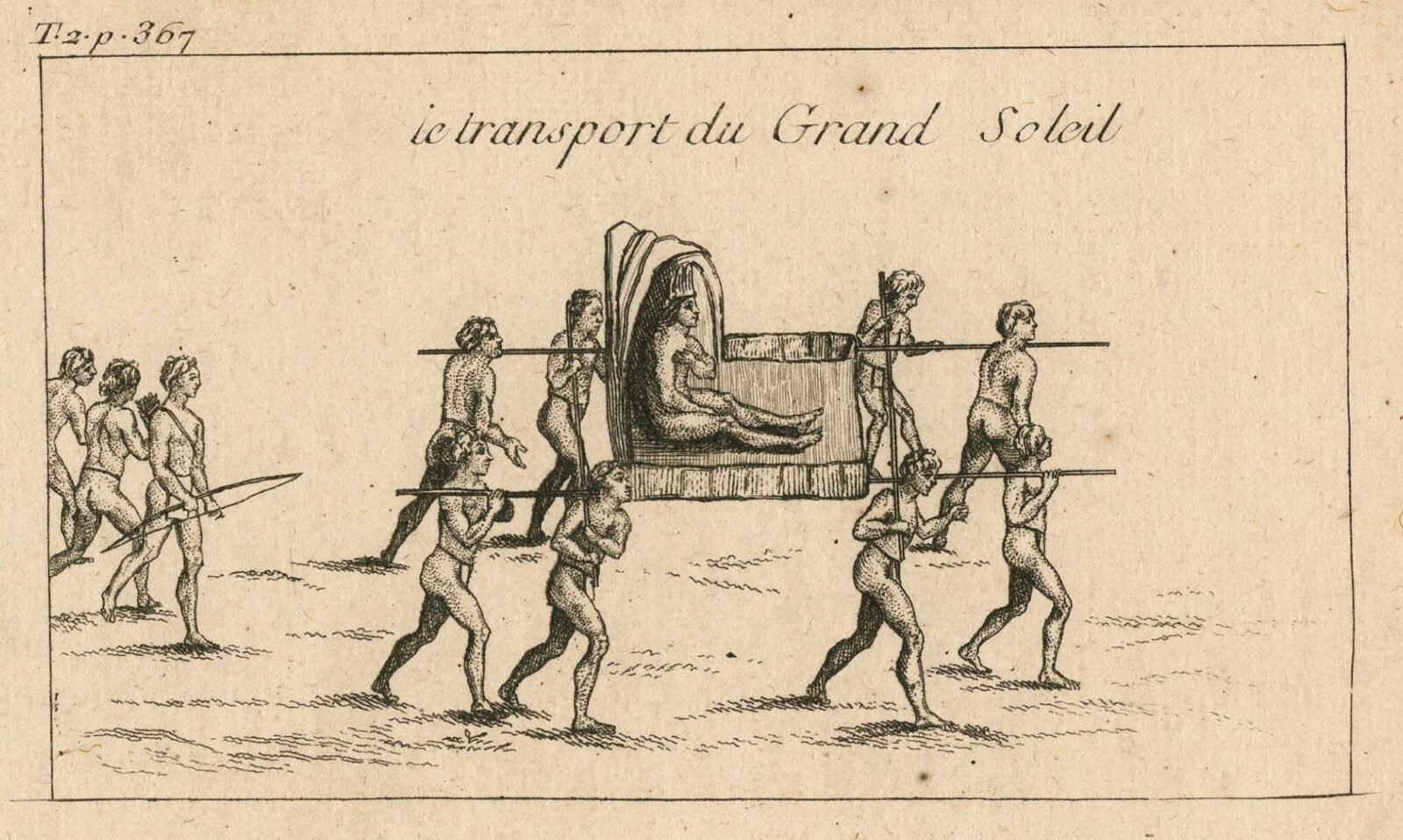

Le transport du Grand Soleil by Antoine Simone Le Page du Pratz.

The Natchez were one of several important American Indian groups with settlements along the Lower Mississippi River during the colonial encroachment of the French and British in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The Natchez are known from extensive colonial documentation and archaeological remains in present-day Adams County, Mississippi. Modern archaeologists and historians rely on French narrative descriptions of Natchez ceremonial events to help interpret the use of precolonial mound sites across the Southeast. The group’s ceramics, evidence of building construction, and ceremonial mound centers such as Anna and Emerald in Adams County, Mississippi, link them to the prehistoric Lower Mississippi Valley Plaquemine culture.

Their Plaquemine roots tentatively connect the Natchez with Quigualtam, one of the sixteenth-century chiefdoms documented by the de Soto expedition in its trek across the Southeast (1539–1543). Quigualtam may have been the name of such a chief, whose territory may have encompassed the Lower Yazoo Basin and the Natchez area of present-day Mississippi. In the summer of 1543, remnants of de Soto’s army used the Mississippi River as an escape route to reach Spanish outposts on the Gulf Coast. Quigualtam’s warriors gave chase with enormous war canoes. Quigualtam’s residence was probably one of the large mound centers in this region; however, archaeologists have been unable to confidently identify it.

Natchez Settlements

When the French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, sieur de La Salle led an expedition into the Lower Mississippi Valley in the 1680s, his writings reveal that significant demographic changes had occurred since de Soto’s time. Populous chiefdoms like Quigualtam had been replaced by smaller societies that came to represent the historic tribal groups along the Mississippi, including the Natchez, Taensas, Tunicas, Houmas, and Quapaws.

The French found the Natchez group comprised of a loose confederation of Native settlements they recorded as Grand Village, Flour, Tiou, Grigra, White Apple, and Jenzenaque. Two of these settlements, Tiou and Grigra, were home to Tunican-speaking migrants that had attached themselves to the Natchez. A Koroa settlement, also of Tunican speakers, was documented temporarily a few miles downriver from the Natchez group. A small mound center, Grand Village was the residence of chiefs known as “Great Sun” and “Tattooed Serpent.” Besides the two chiefs, only a few people lived at the ceremonial center.

French maps and narrative descriptions of Grand Village describe a cluster of six mounds on the west side of St. Catherine Creek, a small tributary of the Mississippi. Chief Great Sun lived in a house atop one of the mounds while Tattooed Serpent’s house stood adjacent to a plaza amid the mound group. Two mounds served as platforms for buildings that the French referred to as “temples,” one designated “old” and the other “new.” These temples were repositories for the burials of chiefs and high-ranking tribal officials. The plaza and new temple were the scene of elaborate funeral ceremonies that the French witnessed for an unnamed female chief in 1704 and Tattooed Serpent in 1725. To the horror of European witnesses, the funeral events included human sacrifice, victims of strangulation intended to accompany dead chiefs into the afterworld.

Like numerous other Indigenous groups in the Southeast, the Natchez had a matrilineal society divided into two moieties, or halves of a social group, based on female kinship. (Moieties may be further subdivided into lineages, clans, families, etc.) The two moieties were both competitive and supportive of each other. Among the Natchez, marriage partners were drawn from opposite moieties. Women controlled family farms, and men married into female lineages. Principal crops were corn, beans, and squash, supplemented by wild and semi-domesticated grains, tubers, fruits, and nuts. Armed with bows and arrows and guns acquired through trade with Europeans, hunters killed deer, bear, and smaller game. Fish were abundant in the Mississippi River and the numerous lakes and streams throughout the region.

French and British Competition

Both the French and British aggressively sought alliances with the Natchez as the two colonial powers vied for control of the Mississippi Valley. For their part, the Natchez bargained shrewdly with European agents to gain access to guns, ammunition, blankets, metal tools and utensils, and a host of other materials they could not produce themselves. Throughout the colonial period, deerskin was the principal American Indian currency for French and British trade materials. Despite the appearance of a unified nation led by Great Sun, Natchez leadership was fragmented among the autonomous chiefs controlling each settlement. The Jenzenaque, Grigra, and White Apple settlements developed trading relationships with the British, while the Tiou and Flour settlements partnered with the French. The British-driven Native slave trade, active from the 1680s until 1715, temporarily provided lucrative rewards for the pro-British settlements.

French Colony and Natchez Revolt

After 1700 French-Canadian voyageurs (fur transporters) and missionaries made frequent stops at the Natchez river landing (near present-day Natchez, Mississippi). Seminarian priest Jean-François Buisson de Saint-Cosme lived with the Natchez from 1700 to 1706. In 1713 the Natchez permitted the establishment of a French trading post in the area. Two years later France established the Natchez colony—a French settlement in the midst of Natchez lands—with the construction of Fort Rosalie on the bluff overlooking the river landing. The continued presence of French soldiers and the influx of settlers encouraged by John Law’s Company of the West led to inevitable disputes with the Natchez. The colony’s first enslaved African laborers arrived by 1720.

An alliance with the British led to a series of conflicts with the French that finally exploded in the 1729 Natchez Revolt. The war ultimately led the Natchez to abandon their homeland. Some Natchez fled to a site near present-day Sicily Island in Catahoula Parish. The French captured part of this group and sold them into slavery in the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue. The remaining Natchez migrated to the east to seek safety with pro-British tribes, first the Chickasaws, later the Creeks and Cherokees.

Natchez descendants living among the Muscogee Creek and Cherokee nations moved to the Oklahoma area when their host nations were removed between 1830 and 1850. Some Natchez descendants remained in scattered settlements in the southeast while a small group enslaved by the French in Saint-Domingue may also have descendants in present-day Haiti.