New Orleans Saints

When it was aired, the New Orleans Saints Super Bowl victory in 2010 was the most-watched television broadcast in history, drawing more than 153 million viewers.

Courtesy of Flickr

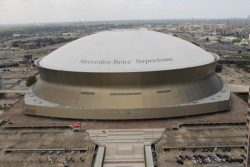

Mercedes Superdome. Seeman, Corey (Photographer)

Since its inception, Louisiana’s professional football team has been a bit different from its competitors—starting with its name. Instead of hewing to standard sports-world monikers employing animal names, the Crescent City’s National Football League entry was christened the New Orleans Saints, in a nod to the spiritual song “When the Saints Go Marching In,” the city’s jazz history, and its sizable Catholic population. Maybe the team’s founders were hoping for some divine help: the Saints were Louisiana’s first major league sports franchise, and the city and state had high hopes for their new team.

Its 1967 debut showed great promise. On the very first play in Saints history, John Gilliam returned the opening kickoff ninety-four yards for a touchdown. Following that auspicious debut, however, the Saints began setting records for futility.

Going strictly by the won-lost column, the Saints endured sixteen consecutive losing seasons. There were some particularly painful indignities, such as being the first team ever beaten by the Tampa Bay Buccaneers; the Bucs had entered the NFL in 1976 and lost their first twenty-six games before beating the Saints midway through the 1977 season. One rare highlight came in 1970, as Saints kicker Tom Dempsey set an NFL record with a sixty-three-yard field goal.

Moving to the Superdome

After playing their first eight seasons at Tulane Stadium, the Saints moved to the Louisiana Superdome in 1975. Located in the heart of New Orleans’s Central Business District, the 72,000-seat stadium was the brainchild of longtime New Orleans civic booster and Saints co-founder Dave Dixon.

For the bulk of the 1970s, fans’ frustration was compounded by the fact that the team had a talented quarterback, Archie Manning. The Mississippi native became a New Orleans favorite with his gritty play and passing prowess, but Manning alone wasn’t enough to bring the Saints a winning season. The closest they came was the 1979 season, when the team finished with a .500 record. The team hit rock bottom in 1980. With fourteen straight losses, their disastrous play prompted New Orleans sportscaster Buddy Diliberto to put a paper bag over his head during a TV broadcast and nickname the team “The Aints.” Diliberto’s stunt gained momentum, and hundreds of fans began wearing paper bags over their heads in the Superdome.

The team’s fortunes finally turned around when new owner Tom Benson hired general manager Jim Finks and head coach Jim Mora. With a defense led by “The Dome Patrol,” a linebacking corps that the NFL Network rated the best in league history, Mora’s teams from 1987 to 1992 made the playoffs four times, although they were never able to win a playoff game.

Fans had plenty to cheer about in 2000, as new head coach Jim Haslett helped guide the Saints to their first playoff win, a victory in the Superdome over the defending Super Bowl champion St. Louis Rams. After his first year as coach, though, Haslett’s squads never lived up to their promise. The 2003–2004 teams narrowly missed the playoffs, the 2003 squad in spectacular fashion, executing one of the most bizarre plays in NFL history on December 21, 2003. Trailing the Jacksonville Jaguars 20–13, the Saints lined up at their own twenty-five yard line for the last play of the game, with their playoff hopes on the line. Quarterback Aaron Brooks threw the ball to Donte Stallworth, who then lateraled it to Michael Lewis. Deuce McAllister took a lateral from Lewis, then threw back across the field to Jerome Pathon, who ran it in for a touchdown. However, elation over the play—later dubbed the River City Relay—was short-lived, as kicker John Carney missed the usually automatic extra point and the Saints lost, 20–19, prompting Saints radio play-by-play announcer Jim Henderson to famously exclaim, “No! He missed the extra point, wide right! Oh my God, how could he do that?”

Hurricane Katrina and the failure of the federal levees in 2005 inflicted heavy damage on the Superdome, forcing the Saints to play their home games for the entire 2005 season at other locations, including Baton Rouge and San Antonio, Texas. Saints owner Benson intimated he was considering moving the team to San Antonio, prompting widespread outcry and a public rebuke from NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue, who declared the NFL’s commitment to keeping the team in New Orleans. Tagliabue’s words were backed up by Gov. Kathleen Blanco, who despite criticism allocated $13 million in state money as part of a $185 million effort to repair the Superdome and reopen the venue at the earliest possible opportunity. The Katrina effect contributed to a dismal 3–13 record for the 2005 season. Benson fired head coach Haslett, setting off a chain reaction of major personnel moves. Former Dallas Cowboys offensive coordinator Sean Payton became the Saints’ new head coach, and the team released inconsistent quarterback Aaron Brooks and signed free agent quarterback Drew Brees.

A Long-Awaited Super Bowl Win

The Superdome reopened on September 25, 2006, for a nationally televised Monday Night Football broadcast featuring the Saints against their longtime division rival Atlanta Falcons. The Saints scored first on an electrifying blocked punt by Steve Gleason on the fourth play of the game, sparking a cathartic, prolonged celebration in the Superdome, and the momentum never waned as the Saints notched a 23–3 victory. On the way to compiling a 10–6 record and winning the NFC South division, the Saints became an emblem of the Gulf Coast’s struggle to recover post-Katrina. The team advanced to the NFC Championship Game for the first time in franchise history, ultimately falling short in its first chance to make it to the Super Bowl at the hands of the Chicago Bears.

Even the football-crazed state of Louisiana had never seen anything like the 2009 season. Bolstered by the aggressive play-calling of new defensive coordinator Gregg Williams and the signing of free agent Darren Sharper, the Saints’ upgraded defense complemented Brees and the offense. A 13–0 start (including beating the vaunted New England Patriots on Monday Night Football) and legitimate Super Bowl aspirations sparked an unprecedented Saints frenzy in the state. As the Saints lost the final three games of the season to drop to 13–3, some pundits and fans worried that the Saints’ dream season had peaked too soon, but those fears were unfounded. In their opening round in the NFC playoffs, the Saints defeated the Arizona Cardinals 48–17. The following week, it was the Minnesota Vikings and quarterback legend Brett Favre’s turn to be denied, as cornerback Tracy Porter intercepted a Favre pass with six seconds left in regulation to keep the game tied and send it to overtime. The Saints won the overtime coin toss and scored first on a Garrett Hartley field goal, prompting a memorable proclamation by radio announcer Henderson: “Pigs have flown! Hell has frozen over! The New Orleans Saints are going to the Super Bowl!”

Super Bowl XLIV was played near Miami, Florida, on February 7, 2010, pitting the Saints against the Indianapolis Colts, who were led by New Orleans native Peyton Manning at quarterback. Two plays from the game will remain forever etched in Saints lore. With the Saints trailing 10–6 at the start of the second half, coach Sean Payton called an onside kick that was recovered by the Saints, opening the door for the Saints to take their first lead of the game. Then with less than five minutes left in the game and the Saints clinging to a 24–17 lead, cornerback Tracy Porter intercepted a Manning pass and returned it for a touchdown. With their 31–17 win, the Saints and their fans finally exorcised decades of frustration. The Saints’ Super Bowl victory was the most-watched US television broadcast in history at the time, drawing more than 153 million viewers.

A Super Bowl victory parade was held in downtown New Orleans two days later. Police estimated 300,000 to 500,000 people jammed the streets to cheer Saints players and coaches and see for themselves the Lombardi Trophy that symbolized the Super Bowl championship. With the event attracting Saints fans from throughout Louisiana and the Gulf Coast, an official of Blaine Kern Studios, which has staged Carnival parades in the city for decades, pegged the crowd estimate at 800,000 and added, “It was more people than we ever had downtown.” Euphoria over the victory continued well into the offseason, as the Saints organization mounted a traveling “Championship Tour” exhibit across the state that drew thousands of fans. Payton and Brees both wrote memoirs based in part on the Super Bowl–winning season, with both books debuting in the Top 10 of the New York Times’s bestsellers list.

Also in 2010, linebacker Rickey Jackson became the first player who spent most of his career as a Saint to be elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Tackle Willie Roaf shared that honor in 2012. Saints general manager Jim Finks, who assembled the Mora-era playoff teams, was inducted as an administrator in 1995. Other Hall of Fame inductees who had tenures in New Orleans include Doug Atkins, Earl Campbell, Jim Taylor, and former coach Hank Stram. Two other former Saints coaches, Tom Fears and Mike Ditka, were elected for their accomplishments as players for other teams.

The Saints reached the playoffs in 2010 and 2011, then stumbled in 2012 as what became known as “the bounty scandal” marred their season. A league investigation determined that from 2009 to 2011, team members were paid bonuses for particularly hard hits and deliberately injuring opposing players. League Commissioner Roger Goodell suspended Payton for the entire 2012 season and general manager Mickey Loomis and assistant coach Joe Vitt for part of the season. Defensive Coordinator Gregg Williams, who was found to have organized the bounty program, was suspended indefinitely, even though he had already left the Saints for another team; four current or former Saints players also were suspended, and the team was fined $500,000 and forfeited second-round draft picks in the 2012 and 2013 drafts. Amid the disruption, the Saints struggled to a 7–9 record in 2012. After a year in exile, Payton returned in 2013 to a hero’s welcome from Saints players and fans, and Benson signed him to a new five-year contract, paying him $8 million a year and making him the highest-paid head coach in any professional sport in the United States.