Alejandro O’Reilly

This entry provides a biographical overview of Alejandro O'Reilly, the second Spanish governor of Louisiana.

LOUISIANA STATE MUSEUM

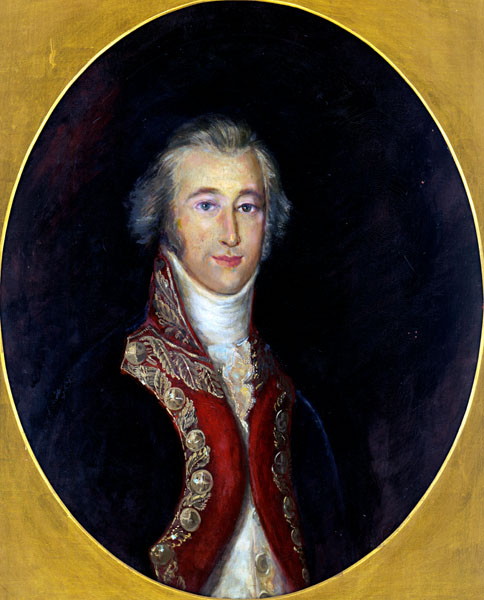

A portrait of Alejandro O'Reilly by Aurora Lazcano.

Alejandro O’Reilly served as the second Spanish governor of Louisiana from 1769 to 1770, consolidating control of the colony and reforming its government, laws, and economy. His most pressing duty on arrival was to punish the ringleaders of the Insurrection of 1768, who had resisted the colony’s transfer to Spain. As a result of the executions that O’Reilly promptly carried out, he was known in Louisiana as “Bloody O’Reilly.”

Early Career

He was born Alexander O’Reilly to an upper-class Irish family in 1722. Many Irishmen at the time left Protestant English domination in their homeland to serve as mercenaries (known as “Wild Geese”) for Catholic rulers on the mainland, and O’Reilly, following his father’s lead, joined the Spanish infantry at the age of ten. He fought for Spain in Italy, and during the Seven Years’ War, he served as an officer in the Austrian, French, and Spanish armies. He successfully led the Spanish invasion of Portugal, England’s ally in the war, which won him a promotion to major general from Spain’s King Charles III. When England relinquished Cuba in the 1763 Treaty of Paris that ended the war, Charles III sent O’Reilly to reoccupy Havana and to determine the necessary steps to restore Cuba’s profitability. O’Reilly performed similar services in Puerto Rico, then returned to Cuba, where he married Rosa de Las Casas, whose brother would become Cuba’s governor in the 1790s. Recalled to Spain in 1764, O’Reilly founded an officer training academy based on Prussian innovations in warfare. He further demonstrated his prowess in 1766 when, as military governor of Madrid, he defended the king’s palace from citizens rioting over grain prices.

Spanish Governor of Louisiana

France had ceded Louisiana to Spain in the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau, but the French and Creole colonists did not willingly acquiesce to the new regime. In 1768, a crowd of New Orleanians dissatisfied with Spanish rule rebelled and ejected Governor Antonio de Ulloa. Charles III dispatched General O’Reilly to Havana to gather sufficient troops for restoring order, and in July of 1769, twenty ships carried an army of two thousand men under O’Reilly’s command to reestablish Spanish sovereignty in Louisiana.

Within days of assuming charge in New Orleans, O’Reilly ordered thirteen of the rebels detained; one died resisting arrest, and a French official was eventually sent home. O’Reilly issued a general pardon for the rest of the populace who had taken part in the uprising, provided that they agreed to swear devotion to Charles III. After two months of legal proceedings, the insurrection’s leaders were convicted of sedition and treason. Six of the men were sentenced to prison in Havana, and the other five were executed by firing squad the following day. Nearly forty years later, a street was built at the site where the rebels were shot; named “rue des François” in their honor, it is still called Frenchmen Street today.

O’Reilly instituted many worthwhile reforms in Louisiana during his six-month governorship. By the time the general returned to Havana in March 1770, he had established a cabildo, the Spanish model for colonial governments, and issued the “Code O’Reilly,” aligning Louisiana’s legal system with that of Spain. Among his reforms was limiting the number of drinking establishments in New Orleans, which had gained a reputation for its high number of rowdy taverns. By proclamation of October 8, 1769, O’Reilly allowed twelve taverns, six billiard halls, and one limonadier (lemonade vendor) to serve alcoholic beverages. The regulation prohibited criminals, vagabonds, and prostitutes from frequenting these establishments, and it forbade the use of swear words and blasphemy.

O’Reilly worked to improve relations with Native American tribes and reorganized the colony’s defenses. He is also credited with stabilizing finances, establishing price controls on food staples, raising standards for medical care, and restricting trade to Spanish ships and Spanish ports. Because the colony frequently experienced food shortages, however, the Irish merchant Oliver Pollock secured the privilege to trade by supplying flour at far below the market price. A decade later, during the American Revolution, Pollock would use his resources to help the Spanish provide much-needed supplies to the Continental Army through the port of New Orleans.

Later Career

As a reward for O’Reilly’s many services, Charles III bestowed upon him the title of Conde (count) in 1772 and an annual pension. In 1775, O’Reilly led an unsuccessful invasion of the African port city of Algiers, but nevertheless achieved the governorship of Cadiz, Spain, in 1780. He resigned the post eight years later, retired to Valencia, and died in 1794.

Adapted from J. Preston Moore’s entry for the Dictionary of Louisiana Biography, a publication of the Louisiana Historical Association in cooperation with the Center for Louisiana Studies at the University of Louisiana, Lafayette.