Robert Mills Lusher

Confederate official and Reconstruction-era Superintendent of Education for the State of Louisiana

The Historic New Orleans Collection

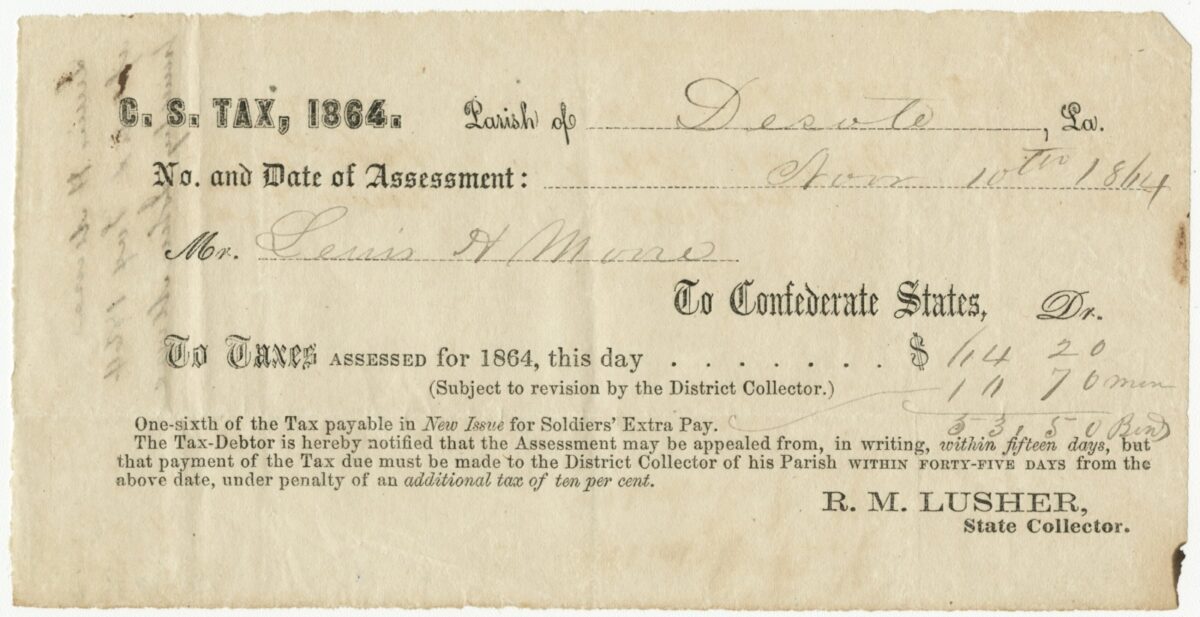

Confederate States of America Tax Assessment, November 10, 1864, showing Robert Mills Lusher as state tax collector.

Robert Mills Lusher (1823–1890), a writer, journalist, and educator, served as Superintendent of Education for the State of Louisiana from 1865 through 1868 and again from 1876 through 1879. The state’s most influential advocate for free public schools as a means of promoting the myth of white supremacy, Lusher wrote, circa 1866, that a primary goal of education is to “vindicate the honor and supremacy of the Caucasian race.” Toward this end, he also established one of the state’s first “normal schools” to educate future (white) teachers, launched the Louisiana Journal of Education, and served as a Louisiana agent for financier and philanthropist George Peabody’s Peabody Education Fund, a charity providing funding for racially separate and unequal public education in the South following the Civil War.

Early Life and Arrival in Louisiana

Lusher was born in Charleston, South Carolina, to George Lusher and Sarah Mills. While attending Georgetown College (now Georgetown University), he clerked for his uncle, architect Robert Mills, who is best known for designing the Washington Monument along with numerous federal buildings in Washington, DC. Lusher first arrived in Louisiana with cousin Alexander Dimitry, who in 1842 became the state’s first Superintendent of Education and would later serve as ambassador to Costa Rica and Nicaragua. In Louisiana Lusher joined Dimitry in both educational and journalistic endeavors, serving as the English-language editor of the Democratic newspaper Louisiana Courier. Lusher graduated from University of Louisiana’s law school in 1850 and married Augusta Salomon, a native of New York, the following year. Their children included two daughters, Mary and Cecelia.

By 1860 Lusher had entered education and was overseeing the state’s normal school program to train teachers. He later wrote in his memoirs that he used his position to ensure continued racial segregation, stating that he had “supported a Normal Department for colored students, in ‘Straight University,’ to free the Peabody Normal Seminary from unfortunate appeals to the admission therein of colored students.” He added that his actions saved “no less than nine thousand white children” from “moral contamination.”

The following year Louisiana became the sixth slaveholding state to secede from the Union. Lusher quickly rose to prominence in the Confederacy, becoming the chief tax collector for Louisiana. He demonstrated his commitment to both his position and the Confederate cause when, commanded by future Kentucky governor Simon Bolivar Buckner, Lusher destroyed his office’s tax records and $11,000,000 in Confederate currency rather than have it seized by Union forces.

State Superintendent of Education

Lusher began his first term as state Superintendent of Education in 1865. That year he wrote to Louisiana governor James Madison Wells to make clear his belief that public schools should serve the cause of white supremacy: “I do not propose, sir, to dilate on the instruction of black and colored … but I shall refer, chiefly, to that of the white educable children, between six and sixteen years of age—the spes ultimae Louisiana—the main hope of our beloved State—our only existing pledges for the perpetuation of her dignity as an enlightened commonwealth.” After serving for three years as schools superintendent, Lusher refused to seek another term, because he would have been required to enforce Article 135 of the Louisiana Constitution of 1868, which prohibited state funding for segregated schools.

As an agent for the Peabody Education Fund in Louisiana, Lusher continued to champion segregated schools, noting in 1867 that “free schools” do not mean “schools equally open to blacks and whites.” Lusher also served as a leader in ex-Confederate attempts to regain control of the civic and cultural life of New Orleans and Louisiana. In 1870 he helped organize memorial ceremonies for Confederate general Robert E. Lee at the St. Charles Theatre. Four years later, on September 14, 1874, ex-Confederates and their sympathizers reconstituted themselves into the paramilitary Crescent City White League to attempt a violent overthrow of the Reconstruction-era state government. While Lusher’s actions during the siege are not known, the White League sought to remove the Black educator William G. Brown as the state’s school leader in order to reinstate Lusher. A year later Lusher was seated in a place of honor when the White League gathered at St. Patrick’s Hall to commemorate the assault. Then, following the end of Reconstruction in 1876, Lusher returned to his position as state Superintendent of Education.

Lusher’s wife Augusta Salomon Lusher died in 1874. In 1881 Robert Lusher married Alice Lamberton, a former student who would later become principal of Sophie B. Wright High School. Alice Lusher echoed her husband’s white supremacist views. In a 1929 Times-Picayune profile, she recalled without regret how she’d joined a student strike in 1874, when she was a high school senior: “A negro superintendent was put in office over us and every high school boy and girl refused to take a diploma as a consequence.” She finally accepted her diploma when Lusher became superintendent, marrying him four years later.

Later Years and Legacy

Lusher spent the last decade of his life editing his Louisiana Journal of Education, where he published articles arguing for “manual training” for Black students and the removal of rights from Black citizens. He also penned his unpublished memoirs, filling the pages with reflections from a lifetime of trying to achieve white supremacy through public education. He wrote how he had urged police juries to support the “thorough education of white children, in rural Louisiana, so that they would be properly prepared to maintain the Supremacy of the white race in rural Louisiana.” He also recalled how he had to go before the state legislature to protest “so degenerate a white citizen as Gov. Madison Wells” and argue against what he called Wells’s proposal to “abolish the white public schools in Louisiana, and to open public schools for colored children in their place!”

Lusher died of heart disease in 1890. In 1913 New Orleans Mayor Martin Behrman dedicated a new school on Willow Street in uptown New Orleans in Lusher’s name. Later named Lusher Charter School, it would eventually extend to three schools across two campuses. Following more than a decade of protest from students and other community members over the continued endorsement of Lusher’s name, the school’s board of directors voted to change the educational institution’s name to the Willow School on April 23, 2022.