White League

A paramilitary organization aligned with the Democratic Party, the White League played a central role in the overthrow of Republican rule and intimidation of African Americans in Louisiana during Reconstruction.

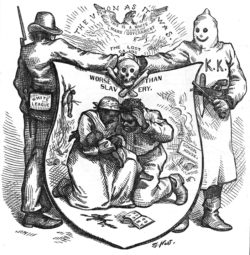

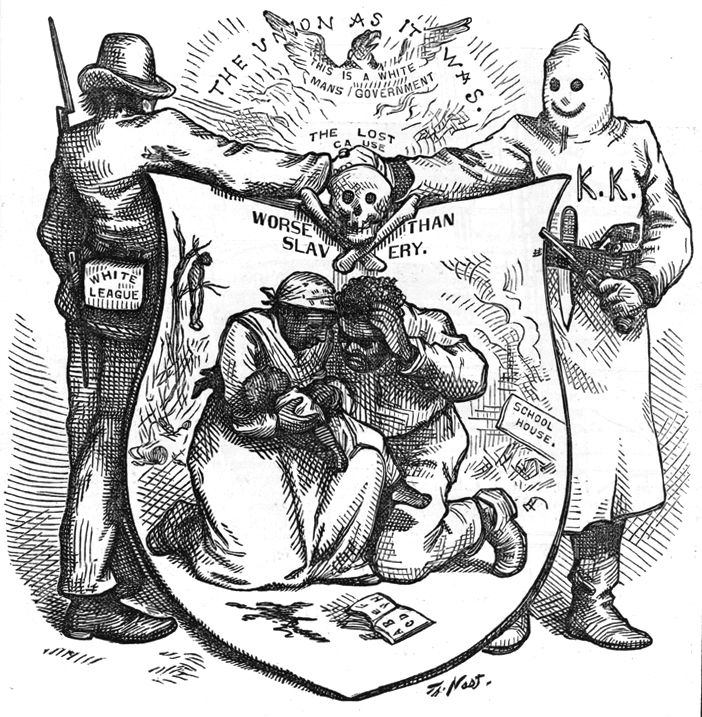

Thomas Nast

"The Union As It Was" by Thomas Nast, Harpers's Weekly, 1874.

A paramilitary organization aligned with the Democratic Party, the White League played a central role in the overthrow of Republican rule and intimidation of African Americans in Louisiana during Reconstruction.

Although calls for a “White Man’s Party” had been heard in Louisiana ever since Black men gained the franchise in 1868, they grew numerous in the tumultuous postbellum years of Union occupation in the 1870s. As Northern “carpetbaggers” arrived in the state they came to dominate the Republican party, which espoused voter registration and civil rights for formerly enslaved people and other African Americans. The contested gubernatorial election of 1872, in which the Republican, William Pitt Kellogg, prevailed over his “Fusionist” opponent, John McEnery, coincided with the first of a series of cases in which Black plaintiffs successfully sued white Louisianans who had violated civil rights and public accommodation statutes. These Black victories in Republican-controlled civil courtrooms fueled fear among white voters and created an atmosphere receptive to the use of white supremacist rhetoric for creating a unified conservative opposition to Republican rule. The defection of white voters from the Republican Party during and immediately following the election of 1872 was a related byproduct of this dynamic and contributed heavily to the racial polarization of politics in Louisiana.

A Mobilization of White Supremacists

We will probably never know who coined the term “White League,” but its phraseology surely resonated with white Louisianans of the postbellum generation. The name evoked bitter recollections of the Union or Loyal leagues that sprouted in Louisiana and elsewhere across the South in the wake of General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. The nineteenth century was an era in which politically active men belonged to one or more clubs of a political nature. Seeking to forge a constituency among recently enfranchised Black men, Republicans appealed first to Black veterans, and later, to freedmen and formed this constituency into local clubs, or leagues. These Union and Loyal leagues served as a mechanism for inculcating Black voters into this important aspect of American political life, while at the same time broadcasting Republican rhetoric to a receptive audience. A substantial plurality of white southerners looked upon these organizations as anathema.

The first articulation of a White League emerged during a meeting at the St. Landry Parish courthouse in Opelousas in late April 1874. While planning for the upcoming political season of nominations and elections, the St. Landry Democrats also called for the formation of a political movement grounded in the foundations of white supremacy. Giving it the name “White League,” the committee printed its proclamations in the Opelousas Courier the next day, setting into motion a chain reaction that fostered the formation of similar clubs in neighboring parishes. The White League spread quickly throughout Acadiana in late spring and reached New Orleans by late June.

Thus, from one standpoint, the White League emerged as part of the political culture of late nineteenth-century America, albeit in a campaign to restore white supremacy through political means. In rural Louisiana as well as in cities like New Orleans, many parish and ward Conservative or Democratic clubs simply renamed their organizations from something like the “Fifth Ward Democratic Club” to the “Fifth Ward White League.”

Transition to Paramilitary Organization

The White League quickly migrated from being a political organization to taking on a paramilitary identity and structure. Its leaders were “captains” and “lieutenants” and membership also held rank such as “first sergeant” or “private.” This was both a reflection of the broad influence of Confederate veterans in the organization, but it also betrayed a growing militarization of politics and the role that violence and intimidation had played in determining political outcomes since the start of the Civil War. In this regard, while the League attracted earnest individuals who embraced it as part of the political process, the emphasis on militarism also attracted a violent element that thirsted for the blood of Republicans. The degree to which a White League would pursue the violent intimidation tactics one normally associated with the Ku Klux Klan hinged entirely upon the sort of men who dominated a locality’s club. Unlike the Democratic Party, the White League had no statewide platform, and individual chapters had unique characteristics, often dwelling upon issues of a local nature and even serving as a vehicle for individuals seeking redress for old personal animosities.

The militarized nature of the White League reached its most mature form in New Orleans, where the league was best organized and by far the largest. Capably led by veteran Confederate officers, the league in the metropolis attracted considerable support from the rising generation of native-born white men who had been too young to fight in the Civil War and who hungered both for manly adventure and a chance to reclaim political control over Louisiana. The Crescent City White League purchased large quantities of arms and ammunition and drilled its members throughout the summer of 1874. By September, it resembled more closely an army than it did the aggregation of political clubs from which it grew. This was no accident, for the objectives of the league had shifted away from merely showing force in support of the coming November mid-term elections to a possible violent overthrow of Louisiana’s Republican government.

Reconstruction Violence

While there are many hazily documented references to White League activity during Reconstruction, two particularly violent episodes in Louisiana can be clearly attributed to the direct efforts of White League clubs. In late August 1874, elements from an unruly White League chapter murdered six white and four Black Republicans in Red River Parish during a multi-day episode known as the Coushatta Massacre. While politics served as the premise for conflict, local animosities and individual bloodlust fueled the deeds of its actors. Two weeks later, on September 14, 1874, thousands of men fought each other in the streets of New Orleans when the Crescent City White League made a failed strategic bid to overthrow the state government in a clash popularly dubbed the Battle of Liberty Place. While more than thirty people died in the battle, it was fought largely between armed combatants who had clear political outcomes in mind. Indeed, the leadership of the Crescent City White League feared that the sort of murderous outrages perpetrated at Coushatta would undermine their efforts to cast themselves as a wronged people rising in popular rebellion.

While the origins, scope, and objectives of these two actions differed greatly, both encapsulated an essential truth about Reconstruction in Louisiana: by the summer of 1874, not only were Republicans unable to protect their constituency, they could not protect themselves. The league had been prevented from overtaking the state only by the presence of federal troops, whom they carefully avoided provoking. What was doubtlessly even more discouraging to Louisiana’s Republicans was that a growing number of editors in the national press now supported the White League’s efforts to obtain what it termed as home rule.

Legacy

The White League last appeared as a force during the chaotic weeks leading up to the Compromise of 1877. Supporting the government of Francis T. Nicholls, the league patrolled the streets of New Orleans and secured the Supreme Court of Louisiana, then housed in the Cabildo on Jackson Square. When Nicholls took office later that year, the league dissolved as a political body but was in large part recast as the nucleus of a new Louisiana National Guard.

That individuals joined the White League for so many different reasons makes easy characterization of its legacy a complex task. Yet perhaps the White League’s most influential legacy was that its memory, both real and imagined, would serve as a model for successive generations’ efforts at maintaining white supremacy through the rhetoric of fear.