St. Louis Cemeteries No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3

Established in 1789, St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 is the oldest cemetery in the city of New Orleans.

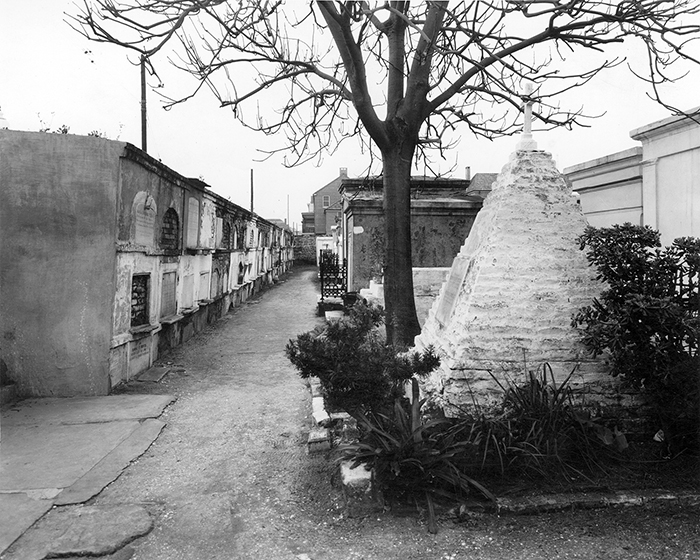

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

St. Louis Cemetery 1. Charles L. Franck Photographers (Photographer)

During New Orleans’s earliest years, though in-ground burial was not uncommon, aboveground tombs reflected the city’s French and Spanish heritage, and their continued use was probably a result of periodic flooding. Because the tall tombs resemble small houses crowded together, the cemeteries of New Orleans are often referred to as “cities of the dead.” Travel writer Edward Henry Durell (Henry Didimus), who visited New Orleans in the midnineteenth century, described the local practice of burial in his book New Orleans As I Found It (1845): “This method of above ground tomb is adopted from necessity; and burial underground is never attempted, except … for the stranger without friends or the poor without money, and they find an uncertain rest, for the water, with which the soil is always saturated, often forces the coffin and its contents out of its narrow and shallow cell, to rot with no other covering than the arch of heaven.”

St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 (1789)

St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 is the city’s oldest burial ground still in existence, and people continue to be buried in its tombs. During the first decades of New Orleans’s development, colonists buried their dead just inside the back wall of the settlement, in the block bounded by Toulouse, Burgundy, St. Louis, and Rampart Streets. By the 1780s, however, that cemetery was reaching its capacity, and the town was growing up around it. In 1789 officials of the Cabildo, the Spanish colonial governing body, created a new cemetery in a low-lying area on the outskirts of town that was too swampy for any other use.

Located just beyond the Vieux Carré’s boundary, bordered by St. Louis, Basin, Conti, and Treme Streets, St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 is crowded with aboveground tombs, separated only by narrow and tortuous paths. Most of the tombs are simple rectangles, taller than they are wide, with flat, curved, or gable roofs. Constructed of brick, the tombs were covered with plaster and then whitewashed, sometimes tinted with color ranging from yellow ochre to red. The tombs usually contained space for more than one body, as they were intended for use by generations of a family. When a new burial was necessary, the bones of the current occupant were swept to the rear of the tomb or placed in an ossuary in order to provide room for the new interment.

The cemetery, like the others in New Orleans, contains a few multistory tombs that accommodate several burial vaults. Called society tombs, they belonged to fraternal or benevolent societies and were intended to ensure the decent burial of their members. The high brick walls enclosing the cemetery contain wall vaults (or fours) on their inner surfaces, with openings covered by brick or marble slabs. These vaults were a less expensive alternative to the freestanding tomb. Sale of the vaults was a source of revenue for the city.

In 1811 Benjamin Henry Latrobe (1764–1820) designed the tomb for Gov. William C. C. Claiborne (1775–1817), who later was reburied in Metairie Cemetery. Benjamin Latrobe and his son Henry are buried in the ground in the cemetery’s rear in an area that originally was outside the cemetery, designated for those who were not Roman Catholic. Etienne Boré (1741–1820), sugar refiner and first mayor of New Orleans, and Marie Laveau (1801–1881), a voodoo practitioner, are both buried here. Homer Plessy (1862–1925), the Creole shoemaker whose US Supreme Court case, Plessy v. Ferguson, unsuccessfully challenged racial segregation, was interred in the Debergue-Blanco family tomb. Ernest “Dutch” Morial (1929–1989), New Orleans’s first African American mayor, is buried in his family’s tomb, which faces that of Laveau. The nonprofit preservation organization Save Our Cemeteries conducts guided tours here, using the fees to restore the ancient tombs in this and other historic cemeteries in New Orleans.

St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 (1823)

By the early nineteenth century, with frequent outbreaks of yellow fever and other diseases causing high numbers of fatalities, New Orleanians feared that vapors emanating from cemeteries were the source of the contagion. City officials procured additional land farther removed from the settled areas of the city for a new burial ground, which was consecrated for use in 1823.

St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 takes up three city blocks and is bordered by North Claiborne Avenue and St. Louis, North Robertson, and Iberville Streets. Originally laid out as one continuous strip with a broad central avenue and narrower parallel side aisles, St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 was divided into three almost square units when Bienville and Conti Streets were cut through. Although this partition diminished the monumental aspect of the central avenue, the arrangement of straight aisles lined with tombs still gave each of the cemetery’s squares a formal order. In the early nineteenth century, cemetery design in the United States was profoundly influenced by the new Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, which combined formal avenues and winding paths, all lined by handsome marble tombs. In New Orleans, where space was limited, cemetery planners adopted the tightly packed, straight avenues of Père Lachaise rather than its spacious, gardenlike aspects. Although not strictly enforced, the social distinctions that existed in life were carried into death in the designation of sections for different religious faiths and ethnic groups.

Many of the most sought-after tomb designers in nineteenth-century New Orleans were French immigrants, among them Paul H. Monsseaux and Prosper Foy, whose son Florville Foy followed in his father’s footsteps. Some of St. Louis Cemetery No. 2’s most striking tombs were designed by J. N. B. de Pouilly, who probably introduced templefronted tombs to New Orleans, in the style of those at Père Lachaise. De Pouilly’s Peniston tomb (1812) is a good example. De Pouilly’s sketchbook (now in The Historic New Orleans Collection) illustrates his interest in tomb design. Particularly noteworthy is his Gothic Revival tomb for the Caballero family (1860), with a trefoil arch in each gable, crockets, and finials. With tombs neatly aligned along straight avenues and many surrounded by low, cast-iron fences, St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 conveys the appearance of a city in miniature. Each of the cemetery’s squares is surrounded by a high brick wall lined with wall vaults; one of them houses de Pouilly’s simple tomb.

St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 is still an active burial ground. The tomb of jazz bandleader Paul Barbarin (1899–1969) is also the resting place of Barbarin’s nephew, jazz musician-historian Danny Barker (1909–1994), as well as Barker’s wife, the singer Louisa “Blue Lu” Barker (1913–1998). Rhythm-and-blues musician Ernie K-Doe (1936–2001) was interred in the family tomb of an appreciative but unrelated fan; K-Doe’s wife and mother-in-law are buried in the same tomb, along with K-Doe’s good friend and fellow R&B musician, Earl King (1934–2003).

St. Louis Cemetery No. 3 (1854)

The state legislature and the New Orleans city council authorized the construction of a new cemetery in 1848, and the following year the wardens of St. Louis Cathedral purchased land on Esplanade Avenue near Bayou St. John. The new tract was not cleared and laid out until the year after the yellow fever epidemic of 1853, which killed 10 percent of the city’s population. First plotted out with three main avenues and four narrower parallel aisles, St. Louis Cemetery No. 3 was enlarged and improved in 1865 by French-born surveyor Jules A. D’Hémécourt (1819–1880). By widening the central aisle and adding cross aisles, he provided grand vistas along the continuous rows of aboveground tombs. The uniform size and gable roofs of the tombs give this cemetery, more than any other in New Orleans, the appearance of city streets in miniature. Francis Lurges fabricated the cemetery’s elaborate iron entrance gates.

Near the entrance is the tomb James Gallier Jr. designed in 1866 for his father, James Gallier Sr., who died at sea during a hurricane, along with his wife, Catherine. It is a vertical composition of stacked pedestals surmounted by a large urn. Among the society tombs, built by and for members of ethnic, religious, or professional organizations, those for the Slavonian Benevolent Society (1876) and the Hellenic Orthodox Community (1928) are particularly impressive; much simpler is the multi-vault tomb of the Little Sisters of the Poor, which was donated by philanthropist Margaret Haughery. Two noted twentieth-century photographers, E. J. Bellocq and Ralston Crawford, are buried in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3. About half of the cemetery’s dozen society tombs and many individual family crypts are still in use.

Every All Saints’ Day (November 1), in these and all other New Orleans cemeteries, families visit their ancestors’ tombs, refresh the whitewash-on-stucco-finished tombs, and decorate them with flowers.