Valcour Aime

Valcour Aime employed the latest technologies and oversaw the creation of an elaborate garden on his sugar plantation.

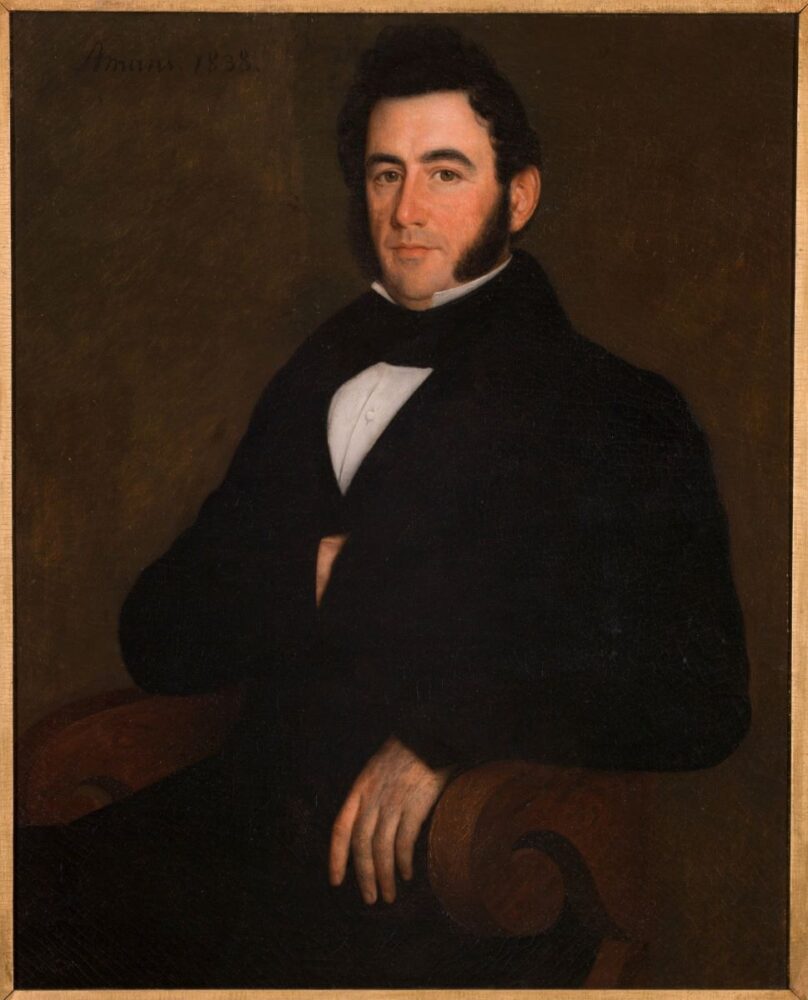

The Historic New Orleans Collection

Portrait of François Gabriel (Valcour) Aime by Jacques Guillaume Lucien Amans.

Valcour Aime amassed vast wealth as a sugar plantation owner, helped revolutionize the sugar industry, and engaged in horticultural pursuits. His diary and the stories told in the enslaved community on his plantation continue to provide important historical and cultural insights.

Family Life

Valcour Aime was born in 1797 to François Aime and Marie Felicité Julie Fortier, descendants of two well-known Creole families. Christened François Gabriel, he was called Valcour by his enslaved nurse, the name by which he would be known for the rest of his life. Orphaned at a young age, he went to live in New Orleans with his maternal grandfather Michel Fortier II. When only sixteen years old, he saw action at the Battle of New Orleans.

His marriage to Josephine Roman in 1819 united two of the state’s most influential families and was the first step in building the plantation dynasty he would one day lead. The daughter of Louise Patin Roman and Jacques Etienne Roman, at the time the wealthiest plantation owners in St. James Parish, Josephine Roman brought a large dowry to the marriage as well as an alliance with her brother, Andre Bienvenu Roman, who later became governor. Aime and his bride resided in her family’s home, and he took over management of the plantation for his widowed mother-in-law. He also purchased the tract of land adjoining her plantation. Upon the death of Louise Patin Roman in 1830 and the settlement of her estate in 1836, Aime’s brother-in-law Jacques Télésphore Roman purchased the Roman Plantation. He then immediately sold it to Aime in exchange for the nearby property Aime owned.

Plantation Business

Aime proceeded to transform the property into a massive plantation complex, complete with sugar refinery and extensive gardens. While many refer to the plantation today as Petit Versailles, it was more commonly known at the time as St. James, after the on-site St. James refinery, where sugar cane was processed and refined. Aime was known for championing innovation in the sugar industry. He embraced the latest technology and did not shy away from experimentation. In 1829 he was among the first sugar plantation owners to utilize steam power, which would transform the industry. By 1832 he had purchased an Archibald Process, a filtering apparatus patented in 1828, to refine sugar, and he also adopted the Rillieux apparatus. Aime’s use of these scientific advancements would have a lasting impact on sugar processing. Aime even traveled to Cuba to observe sugar production on the island.

In addition to his fascination with technology in the sugar cane industry, he was also keenly interested in weather patterns and horticulture. For decades, he maintained a diary that detailed observations of weather patterns, growing conditions, and the plants and flowers present on his estate. He commenced the design, construction, and planting of an English garden, complete with an island and rivulet, grotto, and pagoda, and featuring exotic species of both flora and fauna. He brought in a master gardener from France and assigned a team of enslaved individuals to create and maintain the garden. Aime’s garden was unique for its time and place and would become the stuff of legend, noted in numerous newspaper articles and books over the years.

Brutality of Enslavement

Aime’s riches derived from the exploitation of unpaid labor. At the height of his plantation’s productivity, Valcour Aime enslaved over two hundred people; when those who were sold away or died are taken into account, the number would likely be significantly higher. Due to his meticulous recordkeeping, we are given a window into slavery on his plantation. Runaway slave advertisements show that while managing the plantation for his mother-in-law, he allowed branding to be used on enslaved individuals, a brutal practice customary at that time. From 1821 to 1859, 203 enslaved children were born on his plantation, 58 percent of whom died. When compared to white infant mortality rates of the time, which were approximately 22 percent, it is clear that the children born on Aime’s plantation lacked nutrition, medical care, sanitary conditions, and the necessary time with their mothers to ensure quality care. Most children born there died prior to their first birthdays.

Yet the enslaved community maintained its unique cultural heritage even in the midst of brutal conditions. Aime’s grandson, Alcée Fortier, visited the former slave quarters on the plantation and recorded stories, told to him by the formerly enslaved people and their descendants, of “Bouki” and “Compair Lapin,” trickster tales featuring a rabbit and hyena. These Creole folktales were originally told by natives of the Senegambian region who were captured and sold into slavery.

Late Life

Aime helped found Jefferson College, a school for the sons of elite plantation owners, in 1830. His own son was educated there before being sent to Europe. By 1859, Jefferson College was struggling, and Aime purchased it and saved it from closure.

Though Aime’s house burned sometime around 1920, other houses connected with him still stand. St. Joseph Plantation, a gift from Aime to his daughter Josephine Aime Ferry upon her marriage, and Felicity Plantation, a present to daughter Félicité when she wed Septime Fortier, are maintained just down the road from his former home site. After the death of his only son, Gabriel, from yellow fever in 1854, Aime turned his plantation over to his daughter Edwige’s husband, Florent Fortier, and ceased most business and social activities. However, he did fund various Confederate military companies organized in St. James Parish at the onset of the Civil War.

Valcour Aime died of pneumonia on January 1, 1867, and shortly thereafter his plantation was sold. Portions of his garden still exist today.