Eye in the Sky

A Houma-based blimp squadron

Published: August 31, 2023

Last Updated: November 30, 2023

The National World War II Musuem

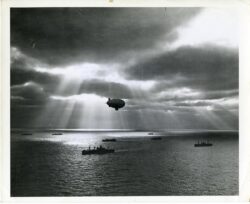

A US Navy blimp watches over a United Nations convoy in the Atlantic Ocean in 1943.

Operation Drumbeat, a German campaign launched in January 1942, was designed to interrupt shipping in US coastal waters along the East Coast and in the south. In the spring and summer of 1942 the gulf became a battleground where German submarines easily targeted and sank largely defenseless US merchant vessels. US Army ports played vital roles in supplying Allied forces, loading nearly 127 million tons of cargo during the war. The New Orleans Port of Embarkation, the second smallest of the eight official Army ports, embarked more than seven million tons from the Poland Avenue facility. Merchant shipping routes drew lines across the Gulf of Mexico into the Caribbean with important cargo. Oil tankers carrying precious fuel from refineries across the coast streamed from gulf waters to propel all manner of vessels toward victory. Oil production increased during the war to meet an astounding demand of five million barrels a day at the height of the war. But getting the oil from source to refinery to where it was ultimately needed was a dangerous business, one that impacted South Louisiana.

In the early days of US involvement in the war, American ships were sitting ducks, helpless against a skilled German U-boat fleet. In the first half of 1942 U-boats sank fifty-eight ships in the gulf. Coastal residents could see flaming wrecks off in the distance. Debris from sunken vessels washed up on the shores. Fishermen and shrimpers aided in rescue and recovery. Hospitals in Terrebonne Parish became triage centers for oil-soaked burn victims, survivors of torpedo attacks and ship sinkings. The war was not a far-off abstraction. As losses mounted, the navy put several measures into place to ensure safe passage of US vessels—convoys, escorts, and increased coastal defense, which included the Lighter than Air (LTA) squadrons—blimps, in layman’s terms.

Blimp bling—“sweetheart” pin in the shape of a navy blimp. The National WWII Museum.

Airships were not new military technology; their use on the battlefield dates to the 1790s when they were used for observation and intelligence gathering. In World War I German forces sent rigid airships known as zeppelins on the offensive, dropping ordnance on targets both strategic and opportunistic. By World War II airship technology had advanced to the point that American dirigibles (steerable airships) were all nonrigid types buoyed by inert helium. Because of limited access to helium, the United States was the only power to use airships during the war.

Advantages of the airship were numerous, but surprise was not one of them. While their drone was somewhat quiet, their size betrayed them—they could be seen from a great distance. Their relatively slow speed (cruising 67 knots or 77 mph), while sometimes an advantage, did not lend itself to a speedy escape in the case of attack. But over open water where air superiority had already been established, the LTA was effective against other slow-moving or vulnerable targets, like U-boats. They were perfectly suited for their main objective, anti-submarine patrol, because they were able to hover low and slow for long periods of time, capable of staying aloft for sixty hours, and could also carry a heavy payload. LTAs also provided a perfect platform for testing and employing new technologies like Magnetic Anomaly Detectors (MAD) and radar.

In the summer of 1942 the navy expanded its airship program from a single base at Lakehurst, New Jersey, identifying several strategic cities across the country to join in this bulwark of coastal defense. The US airship fleet grew from six operational LTAs in 1941 to 166 by the war’s end. The navy’s producer, Goodyear, initially had trouble keeping up with demand, but was able to radically increase production in the latter years of the war.

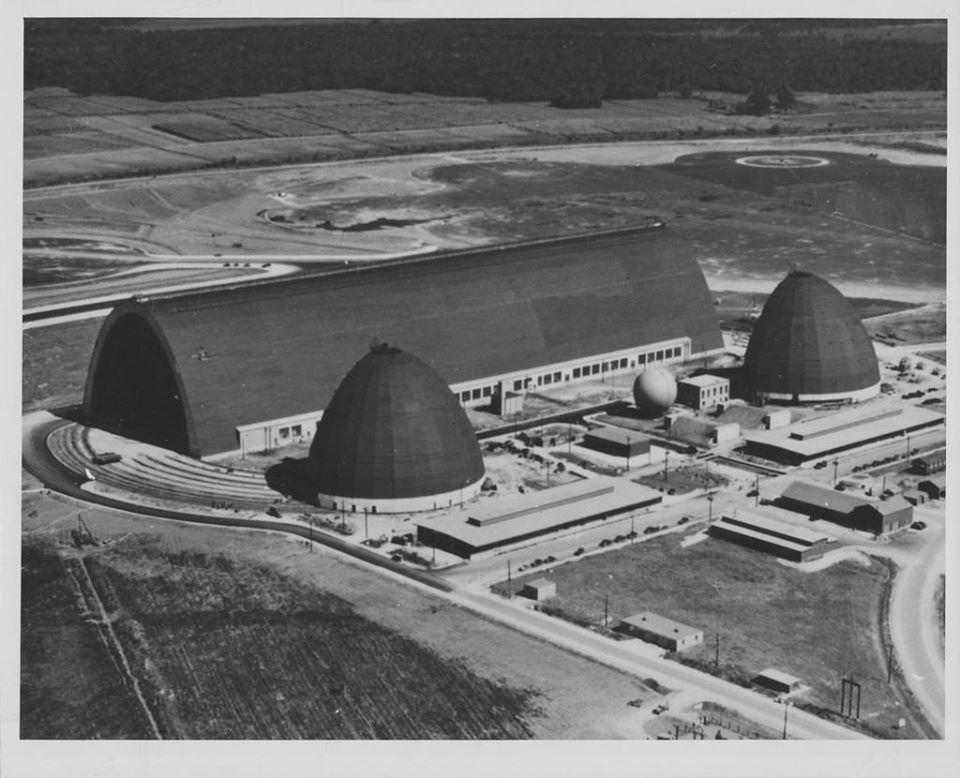

Houma, then a city of nine thousand residents centrally located along the Gulf of Mexico, became home to Naval Air Station (NAS) Houma. In August 1942 construction began three miles outside of city limits on the grassy landing strip of the Houma airfield and roughly 1700 acres of mainly cane fields surrounding it. After a long period of infrastructure development—drainage, excavation, pile driving—barracks, warehouses, and utility buildings rose up.

The most significant endeavor was the erection of the massive hangar—1,000 feet long, 300 feet wide, and 190 feet high—which was large enough to house six fully inflated LTAs. Because of wartime shortages, the building was composed mainly of wood; it became one of the largest wooden structures in the world at the time. Unlike other hangar facilities, which featured sliding, sectional doors, NAS Houma’s hangar featured clamshell doors that detached completely from the building. The doors were so massive that they required seventeen small trucks to move them along the curved railroad tracks on which they sat. Other important features of the site were the mooring out circles used to tether the LTAs while landing and refueling or during maintenance.

Advantages of the airship were numerous, but surprise was not one of them.

NAS Houma was part of Fleet Airship Wing 2. The wing’s other bases included Hitchcock, Texas; Richmond, Florida; and Weeksville, North Carolina. The airbase at Houma was commissioned on May 1, 1943. Two weeks later, on May 14, the first blimp arrived, and its home blimp squadron, Airship Squadron 22 (ZP-22), was activated. At full strength, ZP-22 consisted of six K-ship blimps. They were the whales of the sky, 253 feet long, longer than a modern space shuttle. Powered by two Pratt & Whitney engines, K-ships typically carried four depth charges in addition to a .50-caliber machine gun. The blimp’s crew of ten was situated inside the control car. Operating the huge LTAs was a massive effort that relied not only on the aircrew but also forty personnel on the ground, positioning themselves to land the LTA, obeying instructions conveyed to them via megaphone from the officers above, and catching the hundred-foot mooring ropes that dangled from the blimps. The effort was similar to roping cattle.

Houma’s Airship Squadron ZP-22, or Blimpron 22, also nicknamed the “Bayou Bombers,” began patrols immediately after commissioning. Nearly 150 officers, enlisted men, and marines were based at NAS Houma. In addition to living quarters, the base featured a mess hall, infirmary, post office, bowling alley, movie theater, and pigeon lofts, used to house pigeons employed to carry messages from base to offshore LTAs. The men of ZP-22 took to their new South Louisiana homeland, drawing names for their airships from local lore. The blimps became recreations of pirates and warriors from an earlier time: Jean Lafitte, Dominique You, Nez Coupe. A Walt Disney–designed squadron insignia for ZP-22 featured a flying turtle holding sticks of dynamite. Local residents supported those at the base by donating recreational supplies and hosting fishing trips. Outreach from the base included a column in the Houma Times called “Highlights from the Blimp Base.”

A US Navy blimp drops a depth charge during target practice off Lakehurst, New Jersey, in 1943. The National World War II Museum.

Patrols continued throughout the gulf region in 1943 and early 1944, helping to surveil the area and secure the coast, despite the U-boats having moved on from the region. The work was often dangerous, especially during takeoff and landings. Aviation Machinist’s Mate Second Class William E. Baldwin was commended for saving the lives of two men at NAS Houma. On June 1, 1943, he cut free a fellow ground crewman who had become entangled in a landing rope and was being dragged on the landing mat. Only an hour later, he saved a second man, pushing him free of a rotating propeller.

April 1944 was a tragic month for ZP-22. On April 19, K-133, out on a routine patrol, was lost in a storm in the Gulf of Mexico. After fighting the storm for more than forty minutes, K-133 went down in the gulf. Poor visibility and rough seas hampered a search for the downed blimp. While the crew had managed to escape, nine of the men drowned in the high waves, with only one survivor; Ensign William Thewes was rescued after twenty-one hours in the water, supported only by a life jacket. Catastrophe continued at NAS Houma. In the same storms, wind gusts of 70 mph damaged the hangar, moving the massive doors and disabling closing mechanisms. On April 21 three of ZP-22’s remaining five blimps were torn from their moorings inside the hangar and broke free. Chaos ensued. It was impossible for the station to control the blimps, and K-56, K-57, and K-62 were all lost. Two crashed into fields and power lines and burst into flames; one went down in Bayou Blue. The blimps were unmanned and miraculously no one was injured, but the incident was reported in an Extra edition of the NAS Houma newsletter, the DeLTA News: “It is hard to put into words what just happened, and the things we witnessed Friday morning. To see those huge, quarter of a million dollar blimps burst into the night, to explode and to crash, is a scene we will never forget.” On April 29 the base held a memorial to the nine lost crewmembers of K-133 and a memorial wreath was dropped in the gulf. The squadron was deactivated in September 1944.

Anti-submarine warfare was the primary driver behind expanding airship operations; ultimately, however, US blimps engaged in few actions with enemy submarines. Rear Admiral Charles Rosendahl, who in January 1945 helped compile the report “Operations of Fleet Airships and Costs of Blimp Programs,” argued for the effectiveness of the navy’s LTAs, attributing the low level of enemy engagement to the following dilemma: “You can’t hit ’em where they ain’t.”

In all, only one U-boat was sunk in the Gulf of Mexico, U-166, with all fifty-two crew lost. For decades the sinking was attributed to a torpedo dropped from a Coast Guard aircraft. But another theory was confirmed when the wreckage was discovered in the gulf during a pipeline survey. Given the location and proximity to the wreckage of the SS Robert E. Lee, sunk by U-166 on July 30, 1942, it is now believed that U-166 was hit with depth charges from the Robert E. Lee’s escort, Navy patrol craft USS PC-566.

Aerial view of the hangar, ca. 1943. Regional Military Museum.

While ZP-22 only existed for sixteen months, the navy continued using the bases at Houma. In April 1945, when flood waters overran the Atchafalaya valley, a blimp flown over Houma from the station in Florida was used in guiding and assisting in rescue work, equipped with ropes, life rafts, medical kits, and food rations. Hovering above flooded areas, a blimp crew member would call to residents with a megaphone and gather information to relay to navy rescue crews on the ground. For this and other purposes, the navy continued to use the site until October 1947. Thereafter, the government symbolically leased the property to the city of Houma for one dollar per year. The buildings were further leased to different local companies, and two of the structures were leased to the parish school board for the first African American high school in Terrebonne Parish. In 1948 the massive wooden hangar was deemed a hazard impossible to maintain and was demolished. The resulting wood was estimated to be sufficient to build one thousand average homes. The Times-Picayune that “[t]he hangar materials are going right on in their service to the community—as homes and shops and fishing boats, maybe, in the heart of the bayou country where once the silver giants traversed the skies.”

The story of ZP-22 and NAS Houma is kept alive by the Regional Military Museum in Houma, an institution which covers the history of military activity in southwest Louisiana and the service of those from Terrebonne Parish. When asked about the lasting impact of the blimp base on the area, Executive Director/Curator Dexter Babin spoke about the infrastructure and development created by the $10 million project. After decommissioning the base also became the site of the Houma–Terrebonne airport. Nearby, the cement foundation of the hangar and the arched trusses, which held the wooden framework, can still be seen on Blimp Road. In 2022 the remains of the hangar and the support foundations took on new (after)life as the site of a zombie haunted house. Babin and the Regional Military Museum have applied to designate the site as a National Historic Landmark.

Kimberly Guise is the senior curator and director for curatorial affairs at The National WWII Museum.