Hidden in Plain Sight

Japanese internment in Louisiana during World War II

Published: May 31, 2019

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

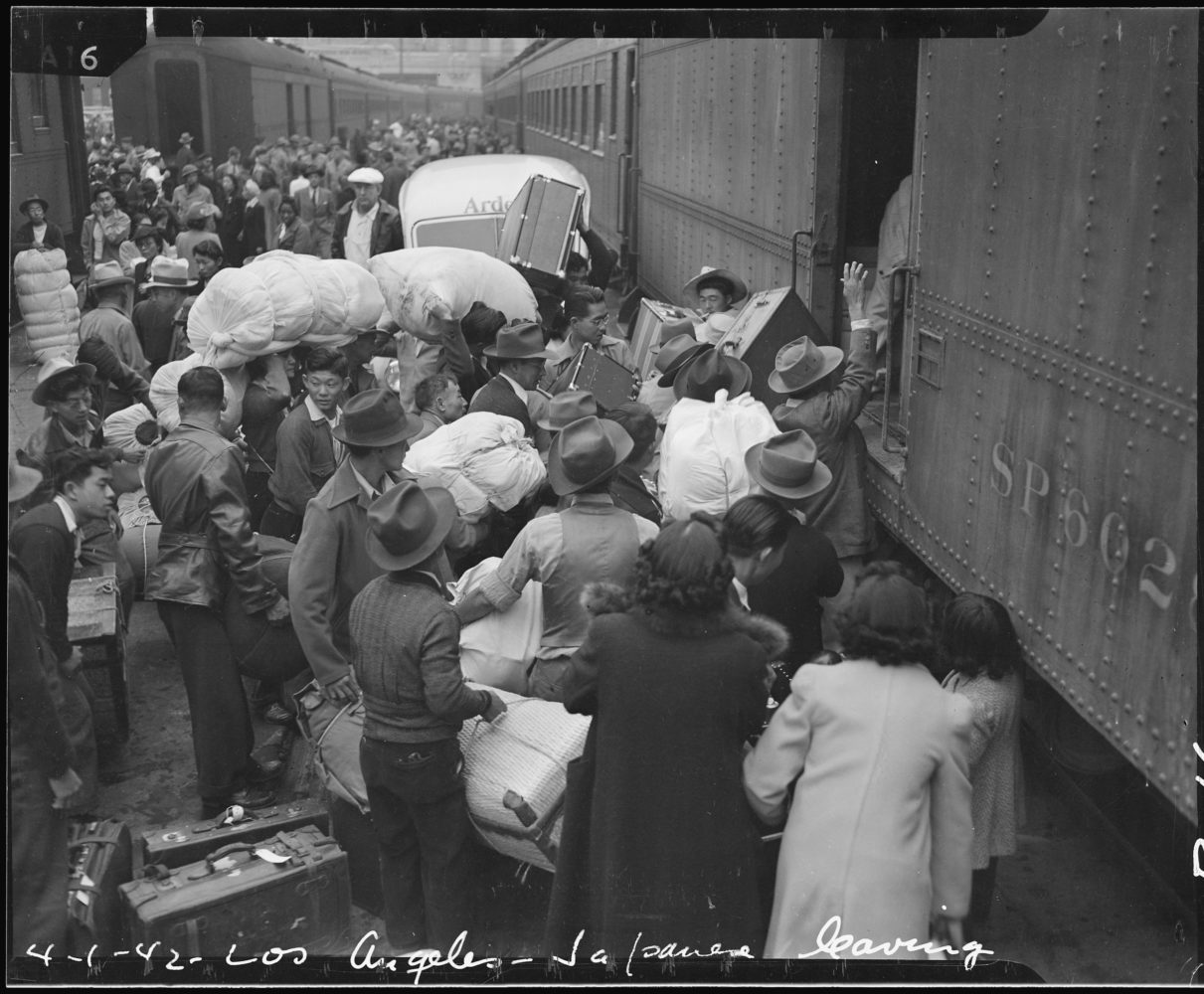

Photo by Clem Albers

Japanese men load their belongings before boarding a train bound for a War Relocation Authority center in April 1942.

Beginning December 7, 1941, as bombs were still going off at Pearl Harbor, authorities began to arrest male Japanese resident aliens and place them into enemy alien internment camps run by the Department of Justice or the United States Army. This timeline may seem surprising—the United States would not even declare war on Japan until December 8—but through a top-secret surveillance program in effect since the 1920s, the United States had identified Japanese alien residents whom they considered threats in the event of a war against the militarizing Japanese Empire. The men were Japanese by birth and had legally immigrated to the United States and its territories, but due to anti-Asian immigration laws, they were unable to become naturalized citizens and instead were given resident alien status. The term “enemy alien” became official when the United States declared war on Japan.

These men were housed at internment camps around the country, and Louisiana was home to an enemy alien internment camp at Camp Livingston, located less than twelve miles outside of Alexandria in the central part of the state.

When war was declared against the Axis nations, the status of all resident aliens from Axis countries residing in the United States changed overnight from “resident” to “enemy” alien. German, Italian, and Japanese aliens were arrested and investigated. A historical precedent for the treatment of enemy aliens had been set with the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, a collection of four bills signed under President John Adams during the “Quasi-War,” a two-year period of naval conflicts between France and the United States. Under the auspices of these acts, internment of resident aliens from hostile countries, now considered enemy aliens, was allowed.

Prior to World War II, the most recent internment of enemy aliens had taken place in 1917 during World War I, with approximately 2,300 German civilians residing in the United States arrested and interned, a total dwarfed by the more than one hundred thousand Japanese and Japanese Americans interned between 1941 and 1946.

One of the youngest internees arrives at an internment camp in Lone Pine, California. Photo by Clem Albers

Beginning in the 1920s, with the rise of Japanese nationalism, the United States Office of Naval Intelligence ran a surveillance program of Japanese resident aliens on the West Coast and Hawaii. The product of this surveillance was the creation of a Custodial Detention List, also known as the ABC classification matrix. This list determined the supposed threat level of individuals and organizations and identified those who should be interned if the United States went to war against the Axis nations. The ABC lists classified aliens into Group A (most dangerous and should be interned), Group B (somewhat dangerous and activities should be restricted), and Group C (least dangerous, not restricted, just generally surveilled). In the hours after Pearl Harbor and beyond, all men classified into these three groups were arrested as enemy aliens. Men were targeted because of their religious affiliation, community influence, service in Japanese-affiliated groups, or simply having been born in Japan.

Many of these men were Issei, or first-generation Japanese immigrants to the United States. Even though most of these men had lived in the United States for several decades, raised children who were US citizens, and had no plans to return to Japan, they were legally barred by federal law from becoming naturalized citizens due to anti-Asian immigration laws, particularly the Immigration Act of 1924. (The racially based immigration quotas in these laws had less striking effects on immigrants from Germany, Italy, or minor Axis powers in Europe, leading to fewer non-citizen residents from those countries finding themselves subject to detention.) Most of these men were immigrant community and business leaders who held positions of power or influence. They were typically Japanese language teachers, newspaper editors, Buddhist priests, or heads of Japanese associations. Their removal deeply affected the communities they left.

Built in 1940, Camp Livingston was a bustling United States Army base named in honor of Chancellor Robert R. Livingston, the negotiator of the Louisiana Purchase. Less than twelve miles from Alexandria, Louisiana, Camp Livingston was located almost in the exact geographic center of the state. This area was home to other military installations and was booming during this time.

Men were targeted because of their religious affiliation, community influence, service in Japanese-affiliated groups, or simply having been born in Japan.

Today, Camp Livingston is mostly remembered as a site for the Louisiana Maneuvers. Beginning in 1941, the maneuvers served as training exercises aimed at transforming the United States Army into a modernized fighting force to be deployed to the European theatre, should the need arise. The period of August to October 1941 saw the largest portion of the training maneuvers take place. Almost half a million men descended on this area of Louisiana and took part in the largest peacetime training maneuvers ever conducted by the United States Army. The careers of Dwight Eisenhower, George Patton, Omar Bradley, and others took off after successfully leading troops in the maneuvers. Camp Livingston’s darker history, as the internment site of men of Japanese ancestry deemed enemy aliens, is seldom discussed, except for in passing references.

As men were arrested due to their ABC status, facilities across the country were built to house enemy aliens deemed threats. Camp Livingston was already under construction as an army base, so it was decided that an enemy alien internment section would be added. The construction of the enemy alien camp facilities began in February 1942 on the southwestern side of Camp Livingston; the facility was built to hold up to five thousand aliens and POWs. Enemy alien internment camps such as the one at Camp Livingston differed from WRA family camps because they were run by different entities and consisted exclusively of men who had been separated from their families. Many of their families in turn were placed in camps run by the Immigration and Naturalization Service, a division of the Department of Justice.

Camp rosters located in the National Archives reveal information on individual men held in Camp Livingston, such as where the men were living when arrested, their occupations, and their ages. The men ranged in age from twenty to eighty, with the majority in their fifties. These men were religious figures, community leaders, teachers, business owners, and fishermen—people with regular jobs and lives. Internees from Hawaii and the mainland began arriving at Camp Livingston in May 1942. At its peak, the internee population is estimated to have been over 1,100.

The men ranged in age from twenty to eighty, with the majority in their fifties. These men were religious figures, community leaders, teachers, business owners, and fishermen—people with regular jobs and lives.

Life in Camp Livingston was both physically and psychologically taxing. The men, separated from their families, went extended periods of time with no news of loved ones and no idea what their fate would be. They performed manual labor in the unforgiving Louisiana heat, cutting and loading pine logs as well as clearing the surrounding forest.

Despite the hostile environment, the men found ways to keep their spirits up. They formed their own government within the camp and developed creative outlets, such as camp classes and artistic endeavors, to make their time in camp more bearable. Suikei Furuya, a Honolulu businessman and poet, recounted his time at Camp Livingston in his memoir An Internment Odyssey: Haisho Tenten. “It was very hot in the barracks and in the pine forest, as well. Someone dug a hole in the ground and found it was more comfortable to be in there, lying down and reading books. I visited the hole and found it to be much cooler indeed. These holes were very comfortable—cool in the summer and warm in the winter. Perhaps this is how the gods taught primitive man to protect himself from heat and cold.”

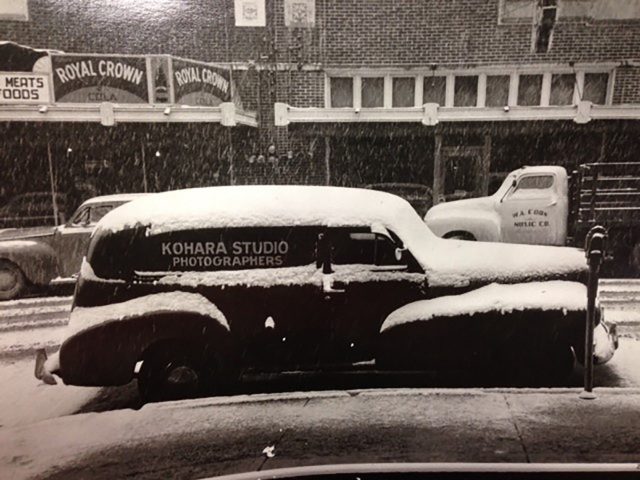

As the internment camp was being built at Camp Livingston, a Japanese family, the Koharas, had been operating a thriving photo studio in Alexandria for well over ten years. Manabu and Saki Kohara, first-generation Japanese immigrants, moved to Alexandria in 1928 after Manabu visited Glenmora, Louisiana, on a photography job. Manabu had previously been based in Iowa, but he decided to move south to become a truck crop farmer, bringing his wife Saki and their five children along with him. After two years, Manabu realized that farming wasn’t for him and pursued photography full-time, opening the Kohara Studio on Bolton Avenue. Manabu passed away just prior to Pearl Harbor, leaving Saki to run the shop with her oldest son Sammy.

Kohara family business’s van. Newcomb Camera Collection, Central Louisiana Collections, James C. Bolton Library, LSU Alexandria

Families who lived in designated military exclusion zones in California, Oregon, and Washington were forced to move inland, into the WRA family camps. Japanese families living outside of these exclusion zones underwent investigation to determine whether they were a threat to the United States. Mere days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Kohara family underwent an investigation by both the FBI and the Treasury Department. Marion Kohara Couvillion was a teenager at that time and recalled her family being put under house arrest: “My mother wasn’t a citizen and at that time they weren’t allowed to become citizens. . . . I can remember the sheriff apologizing to my mother for having to put her under house arrest . . . he said, ‘The FBI is making me do it and I have to do it. So sorry about that, Mrs. Kohara.’ But he was very nice about it. Most of the people that I came in contact with were. They treated me like we treated the Italians and Germans, who were in the same position but weren’t being relocated.”

After a week-long investigation, the Kohara family was determined not to be a threat. On January 13, 1942, the local newspaper, the Alexandria Daily Town Talk, ran a story touting the American-ness of the Kohara family. The article noted that “not one shadow of doubt regarding their patriotism was found.” With the support of community members and the threat of internment removed, the Kohara family was able to continue to operate its photography studio normally, even providing photography services to the surrounding Army camps. The Koharas were also able to freely visit two nearby WRA family internment camps in Jerome, and Rohwer, Arkansas. According to Marion, they viewed these visits to internment camps, which were sanctioned and not uncommon, as social outings; given their isolation as the sole Japanese family in the center of the state, the ability to travel a few hours and socialize with other Japanese was a rare and welcome opportunity. It provided Marion an opportunity to interact with other Japanese children for the first time, and for Saki, it was an opportunity to speak Japanese.

Given their proximity to Camp Livingston and the fact that they were the sole Japanese family in the area, the Kohara family home served as a stopping point for numerous Japanese who were visiting loved ones held in Camp Livingston and the two nearby WRA camps in Arkansas. Because of those two factors, the Koharas became very well known among the Japanese community. When a person who stayed at the Kohara home visited the camp, they told others of their experience and the hospitality they received.

While Sammy helped to run the photography studio with his mother, his two brothers, Jackie and Tommy, took part in World War II. Tommy enlisted in May 1941, six months before Pearl Harbor. He served as a photographer both on the front lines and behind the lines in Germany and France. Jackie enlisted a few years later, serving as an officer in the enlisted reserve/Medical Administrative Corps; upon returning home after the war, he took over the Kohara family photography business. Tommy came home in 1945 and worked as a photographer for both the Louisiana Forestry Commission and then the Alexandria Daily Town Talk, where he was the chief photographer for twenty-five years.

Among the men interned at Camp Livingston was Reverend Hisanori Kano, an Episcopal priest. Nearly twenty-five years after the end of World War II and in preparation for writing his memoirs, Kano visited all the locations where he had been interned. Upon his return to Camp Livingston, where he had spent over a year of his life, Kano was interviewed by Tommy Kohara for the Alexandria Daily Town Talk; Tommy noted in the story that his parents had known Reverend Kano from their days living in the Midwest.

By 1969, Tommy reported, Kano “found the wooded Camp Livingston a far cry from the bustling army camp of the early 1940s and was not sure that he could identify the building foundations, all that is left of the compound where he was interned.” In his memoir, Kano recounts, “when I went back to see three of the old camps, they had been removed and there were forests and woods in their place. The pine, oak, and walnut trees brought back many memories.” A recent visit to the site of Camp Livingston revealed even less: no foundations, no markers, only the trees. Nothing remains of the physical structures of Camp Livingston, and very little is readily available in terms of documentation regarding the enemy alien internment that occurred.

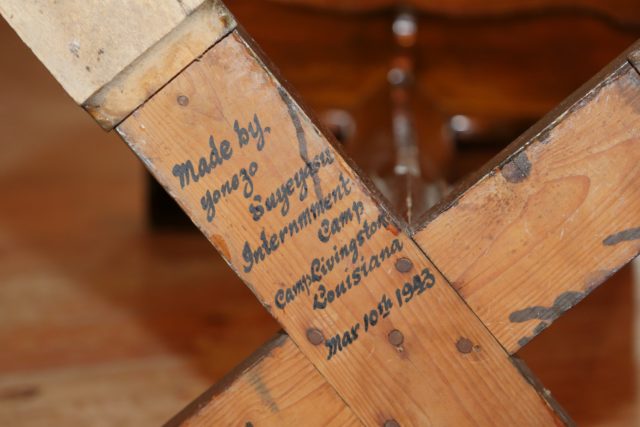

Inscription identifying a podium in the Louisiana Maneuvers and Military Museum collection as the work of internee Yonezo Suyeyasu. Photo by Chris Robert

The Louisiana Maneuvers and Military Museum at Camp Beauregard in Pineville, Louisiana, is the only institution dedicated to covering the famous Louisiana Maneuvers. In addition to highlighting the Maneuvers, the museum also recognizes operations of US military forces. Since the museum opened, a hand-crafted wooden podium on display in its galleries had always been attributed to a Japanese POW held at Camp Livingston. Comparison of the name from the podium plaque to the camp rosters showed that, in fact, its creator was an enemy alien internee, not a POW. Yonezo Suyeyasu, the maker of the podium, was born on March 15, 1887, in Japan and was living in Honolulu with his family when he was interned. He was a carpenter and Shinto priest. In addition to Camp Livingston, he was also held in Camp Jerome in Arkansas and Camp Tule Lake in California. While discovering that this podium was made by an enemy alien internee rather than a POW may not seem groundbreaking, it is what this discovery and podium represent that make it so special: the history of enemy alien internment at Camp Livingston, recorded in a physical artifact.

The work of illuminating and sharing the history of Japanese internment in Louisiana is underway. We are working with the Louisiana Maneuvers and Military Museum to create an exhibit telling the stories of these men and to ensure that this history is made visible and becomes integrated into the narrative of Camp Livingston.

Hayley Johnson is the Head of Government Documents and Microforms at Louisiana State University. Hayley works with government documents in order to highlight their importance and relevance to both historical and present-day issues.

Sarah Simms is the Undergraduate and Student Success Librarian at Louisiana State University. Before entering academic librarianship, Sarah worked in the antiquarian book trade in New York City. Her interests include history, culture, and social justice advocacy.