Five Acres and a Mill

Organic rice cultivation in Rapides Parish

Published: May 31, 2023

Last Updated: August 31, 2023

Photo by Remi Tallo

Mason with new rice seedlings.

Jubilee Justice was established in Oakland, California, in 2017 with a mission to uplift Black farmers, whose numbers have diminished from a million in 1920 to only about 45,000 now. “Black farmers in the United States, and farmers in general, have been so screwed over,” Mason said. “We are certainly working on how to get out of the trap.” With business partner Mark Watson, Mason started the Safe House initiative to shore up at-risk farms. Mason says the duo has raised over $2 million for grants to Black farmers through Safe House.

In 2019 Jubilee Justice launched the Black Farmers’ Rice Project with a pilot site in Rapides Parish. Theirs is the first initiative in the United States committed to following the System of Rice Intensification (SRI), which has been practiced and advanced in many African countries since the 1980s. From its first dry-planted paddies in Madagascar, SRI started as a methodology and has expanded to become an international network of expert farmers and researchers proliferating the growing system. The SRI network’s efforts are supported by a resource center at Cornell University whose aim is to increase global food production capacity in the face of rising hunger on a warming planet. According to the World Bank Institute, SRI has profoundly improved both yields of production and the quality of the rice in India, China, Indonesia, and the Philippines, all countries where rice is a much-relied-upon staple.

Domestically, half of the country’s ten “hungriest states” are in the deep south. Louisiana has the nation’s highest rate of child food insecurity, according to the nonprofit Feeding America. (Food insecurity is defined as “a lack of consistent access to enough food for every person in a household to live an active, healthy life.”) And within our struggling state, Rapides Parish is ranked 38 out of 50 parishes tracked. So when agronomist Erika Styger, founder of Cornell’s climate-resilient farming project, introduced Mason in a serious way to the potential of SRI, her message fell on receptive ears.

“I was like, yeah, okay, let’s do this,” Mason said. “Then I realized, oh, I need land.” She smiled at the memory. “So I called up Elizabeth [Keller], and she said, ‘I have land, come here. Come here.’” Keller’s family owns the Inglewood Plantation site out on Old Baton Rouge Highway, and this is where Jubilee Justice has landed. Mason credits Keller as “an extraordinary person, who has learned from her own life,” who believes that supporting the Jubilee Justice mission can help to tangibly repair the past, and who “has led her family in the right direction.” The Kellers have donated a building on the property to Jubilee Justice, which has beenturned into a rice mill so that the organization can own their means of production. A ribbon-cutting celebration was held mid-May.

“It is not easy to grow rice,” Mason noted. “It’s a sensitive crop, super sensitive, because we’re not flooding the fields.”

Flooding is the easiest way to stop competition from weeds, but not in a world of escalating water scarcity. Even in water-logged Louisiana, at this writing portions of eleven parishes are “abnormally dry,” and two parishes—Terrebonne and Lafourche—are in “moderate drought.” Also problematic is that flooding generates methane-producing bacteria in the rice fields, which per a World Wildlife Foundation report are responsible for 12 percent of global methane emissions each year, equivalent to the annual greenhouse gas output of the entire aviation industry, worldwide.

The Kellers’ commitment to the vision was Mason’s cue to hire Iriel Edwards, a Cornell graduate, as their SRI farm manager to get their now-landed initiative rolling. Edwards began living near the five acres they’d leased from the Kellers. Edwards also began planning the layout of the plots and thinking about the needed infrastructure.

Pretty quickly, Mason realized she couldn’t nurture the project from the West Coast. She’d have to be on site in Alexandria to observe, commune, study, and build, and to plunge her own two hands into the soil known to generations of enslaved cotton growers. Every one of their dashed dreams propel her living, breathing ones. Jubilee Justice has since raised an office near the fields, constructed a hoop house to protect tender plants from the elements, and cleared three plots where they rotate crops—rice, lentils, oats, and sesame.

“I work with a team of people that know way more than I do,” Mason said. “That’s the thing I know how to do well.”

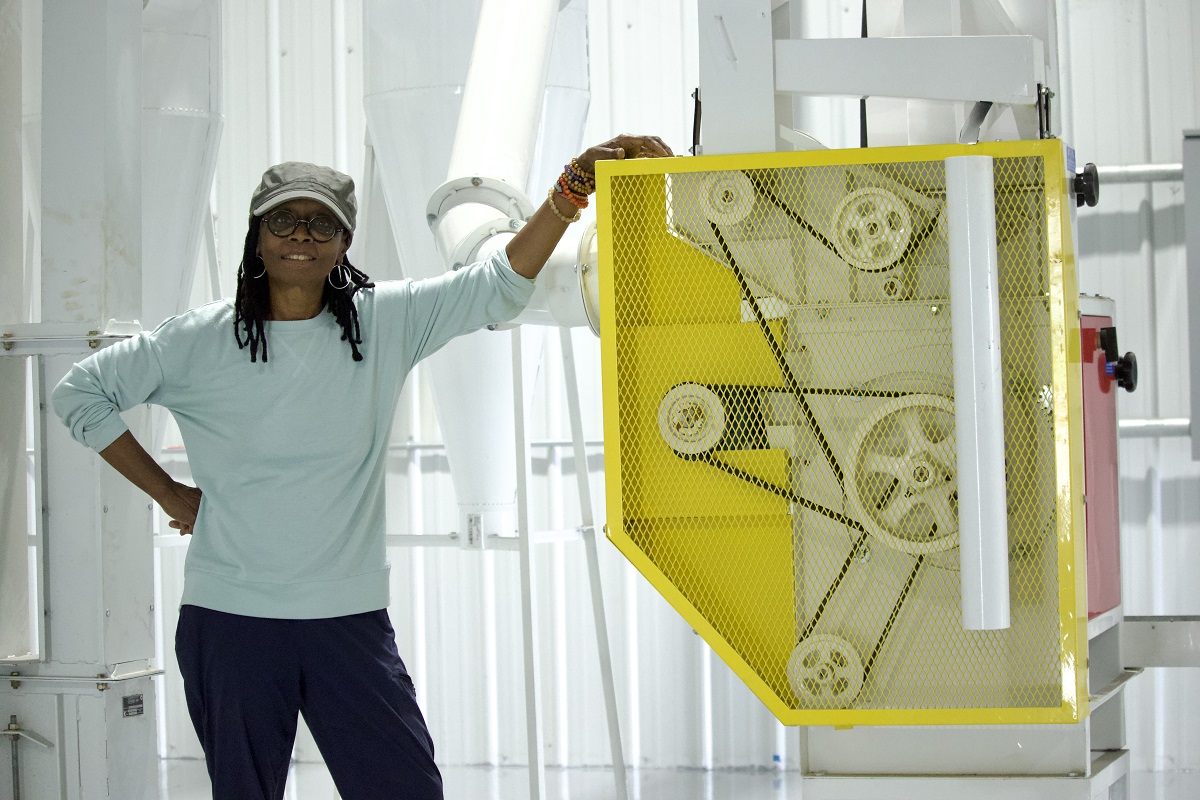

Mason with a rice husk removal machine. Photo by Remi Tallo.

Something else happened after she got to Louisiana. Mason learned from ancestry.com that she was 100 percent descended in her matrilineal line from the Mende people of Sierra Leone. For 3,500 years, the Mende have grown rice, and are one of the progenitors of the technique used in SRI, of intermittent dry growing to allow soil aeration and other benefits.

Eighteen farms in Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and St. Thomas have since joined in Jubilee Justice’s SRI experiment. Styger, Edwards, and Mason regularly visit them, traveling in a big loop in the organization’s RV.

“We share with those farmers what we learn on these trial plots,” Mason explained, “and do a lot of listening too.”

Their biggest challenge has been the weeds. “If you’re not organic you blast them with herbicide,” Mason explained. “But if you’re organic, how do we work with the soil’s health and biology?” They tried covering the rows with fabric and planting through small holes, which prevented the weeds, but starved the soil. Then they tried covering the soil with layers of compost and mulch and planting directly into the hay. It too stopped the weeds, but they had to plant by hand. Now they’re getting a no-till transplanter to cut into the mulch. While hopes are high for the next planting, they’ve learned to temper them because nature, in the form of unpredictably extreme weather, can dash them altogether.

“It’s been frightening,” Mason admitted. “In the freeze we lost this whole plot filled with oats—gone. That one was filled with lentils—gone. We lost it all.”

Only the cover crops, planted to regenerate the soil’s nutrients, made it.

More recently, they’d had what she called a “major water event,” so severe that even the rice crop, which is accustomed to a lot of water, was washed out. “The rain completely flooded our fields. It’s heartbreaking,” she said. “For the plants themselves, and for the work that went into putting them in the ground. It’s an issue for every farmer, and for every person who eats.”

This is when spirit shows itself in the work, she explained. “I have surrounded myself with these beautiful young people, and we constantly talk about how to approach life’s ups and downs. We breathe together, we stretch, and we talk about how we can be steady when things are not.”

Frances Madeson is a freelance movement journalist, feature writer, and author of the comic novel Cooperative Village.