Geographer's Space

Gretna’s Mechanickham

A possible origin of its name

Published: December 3, 2018

Last Updated: May 20, 2019

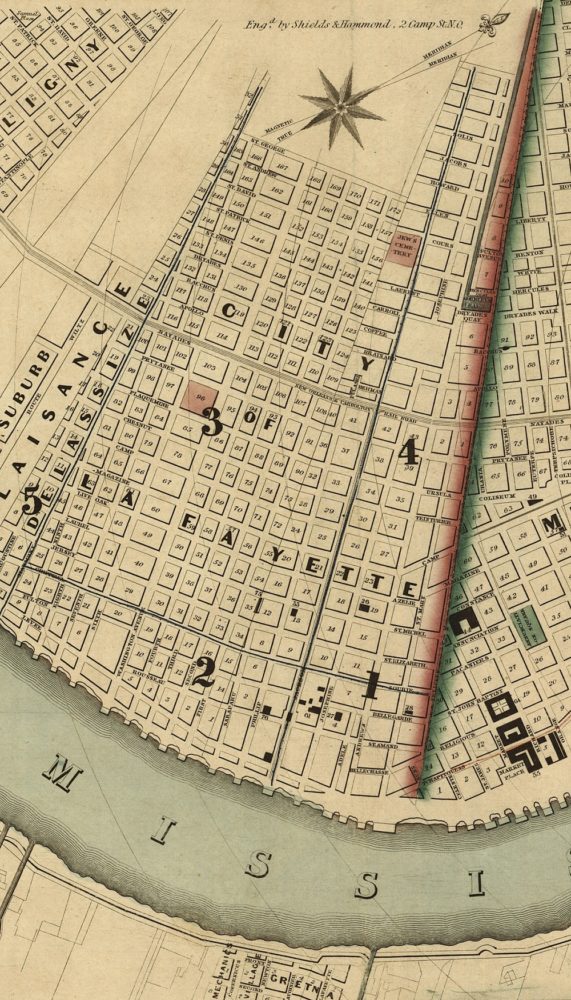

Library of Congress

Detail of Norman’s Plan of New Orleans and Environs from 1845, showing Mechanics Village at bottom center.

Across the Mississippi from New Orleans, within the modern city limits of Gretna in Jefferson Parish, lies a street grid first surveyed in 1836 on the lower of two plantations owned by Nicolas Noël Destrehan. The subdivision originally had the curious name of Mechanickham (or Mechanikham, Mechaniks Village, Mechanickham Village, or Mechanicsville, orthography being rather subjective in those days). The term may derive from an interesting social phenomenon typical of rural America in the nineteenth century, comparable to the proverbial “barn raising”—only in this case, the German-American equivalent of it.

Before we explore the phenomenon, let us examine how Germans made their way to Mechanickham. At first, these newcomers arrived at New Orleans proper, for its maritime accessibility into the interior and for its economic opportunities as the largest city in the South. Much like the thousands of Irish immigrants incoming in this same era, Germans generally settled in the periphery of the metropolis, particularly the “upper banlieue” (upriver outskirts) of the present-day uptown riverfront.

New Orleans at this time extended only up to Felicity Street, above which was a separate city called Lafayette (today’s Irish Channel, Garden District, and Central City neighborhoods). Various groups lived cheek-by-jowl in this muddy wharf-side precinct, which had more than its share of nuisance-spewing industries, not to mention raffish flatboat wharves and herds of livestock hoofing through the streets.

The upper banlieue also had two ferry lines connecting with what at the time was called the “right bank”—today’s West Bank. The service gave left-bank city dwellers the option of living in a more bucolic environment, and there were many reasons to do so: ample land, affordable real estate, space for truck farms, and distance from the dense disease-prone urban core, while at the same time remaining reasonably proximate to the city’s economy and resources.

The right bank had also been developing its own industries, among them ship building and repair, iron foundries, and, in time, railroad linkages to points west. All of these industries required mechanics, and many of the Germans were skilled in various mechanical trades. Upon first arriving to the right bank, they found themselves with a surplus of skilled labor and raw materials (the nearby Barataria swamp had plenty of timber), but a deficit of capital and housing. Culturally, too, Germans were famously collaborative in their relationships; a sociologist would describe them as having “high social capital,” meaning they formed associations, founded clubs, worshipped in various congregations, recreated in team sports and singing groups, and networked themselves into valuable interrelationships.

Put together all the above, and we have the phenomenon of “mechanics’ homes.”

A mechanics’ home was a simple functional dwelling built by Mechanikers—that is, craftsmen of various trades—who had the requisite skills and materials for such a project collectively, but not individually. Each participant’s contribution became a sort of promissory note which could be later redeemed for collective assistance toward a comparable project needed by that participant. In one 1843 article titled “Mechanics’ Home,” the writer described how various skilled workers—a “carpenter, bricklayer and plasterer, [would all] club together and assist in building a house for each other; they then labor for the lumber merchant and others, and by this means pay for the articles used.”

That article came from Portland, Maine, suggesting this custom was not unique to Louisiana or to Germans; indeed, it had equivalents throughout the American countryside, where big projects needed to get done, but big businesses had not yet formed (much less big government) to do them. This left ordinary folks to figure out how to pool their resources and solve local problems on their own. In other cases, including in urban areas, mechanics would join building associations or institutes which would formally coordinate the reciprocal relationships.

Communal work and mutual-aid arrangements also went into raising barns and silos, digging cellars and wells, building roads and irrigation canals, and defending from common threats, like fire. Perhaps not coincidentally, residents of Mechanickham also volunteered themselves to form the Gretna Fire Company, which would later become the famed David Crockett Steam Fire Company No. 1. Today it is the oldest continuously operating volunteer fire department in the nation.

Other examples of nineteenth-century communal work included quilting bees, canning parties, and, in New Orleans, social aid and pleasure clubs, which provided burial insurance and later became known for their second-line parades. One can argue that fish fries, hog roasts, and crawfish boils also have elements of mutual aid or communal work, in that each involves capital outlays and contributions of labor and know-how, all of which are best handled collectively. Plus, they’re fun—just as there was an enjoyable sociable element to quilting bees and barn raisings.

Time and lack of documentation have obscured details of the original mechanics’ homes of present-day Gretna, including their location, architecture, and quantity. They probably post-dated the ferry service from the St. Mary Market and Lafayette terminals (both in operation by 1834), since these conveyances are what brought the German mechanikers across the river. The houses probably preceded the year 1839, when Springbett and Pilié’s Topographical Map of the City and Environs of New Orleans depicted a subdivision labeled MECHANIKS VILLAGE on its upper flank and GRETNA below. Usage of the word “village” suggests this was not just one boarding house but a collection of houses built through mutual aid—as there would have to be, for this system to make sense.

The subdivision itself was the creation of Pierre Benjamin Buisson, a former soldier in Napoleon’s army who had previously surveyed much of today’s Uptown. His design, and the vision of his client Nicolas Noël Destrehan, entailed more than just a functional array of streets, but rather an inspired community for people and commerce. Mechaniks Village had a scenic commons framed by twin boulevards (now Huey P. Long Avenue) addressing the river, space for a church and courthouse or college, and provisions for a railroad right-of-way, a foundry, and a ferry landing. Destrehan also set forth regulations for land-buyers, “allow[ing] the settlers to have their own government,” according to historian Ellen C. Merrill, while also imposing a proto-zoning ordinance strictly prohibiting slaughterhouses of any type—the very sort of land use that drove many people out of Lafayette, with its malodorous stockyards and abattoirs.

In time, the right bank would become the modern West Bank, industry and growth would envelop the old villages and farms, German immigrants would assimilate into the larger population, and the building of houses would become professionalized. Both the phenomenon and the toponym of Mechanickham would fade, and folks came to call the place “Gretna,” especially after its incorporation in 1913.

As for the term “mechanics’ house,” historical usage examples indicate that, in addition to its original meaning described above, the term could also mean a boarding house built collectively for itinerant tradesmen. By the end of the nineteenth century, it came to infer simple functional working-class housing, with only passing regard to how its construction was organized. In 1883, for example, the American Architect and Building News held a competition to design “mechanics’ houses” to suit a working-class family of “a mechanic living on a daily wage of three dollars, who can afford to build only by joining a ‘building association.’”

Today, at the German-American Cultural Center in Old Gretna, an outdoor mural depicts immigrants arriving at New Orleans, with a ferry and the rural right bank in the distance, as well as a street scene and simple wooden houses from the village’s early days. It reads “Mechanikham, 1836” and “Gretna 1913,” and faces out over the same scenic commons Buisson designed to address the Mississippi River.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Cityscapes of New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, Bourbon Street: A History, and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on Twitter.