Geographer's Space

How “Forward Thrust” Reshaped Southern Geography

Relocating a capital city or even government buildings can have dramatic effects on the surrounding area

Published: March 12, 2015

Last Updated: May 19, 2022

Forward-thrust projects usually arise in relatively young and large countries whose primate coastal cities monopolize most economic, cultural, and political power, leaving interiors relatively undeveloped and backward. The world’s best example of rebalancing such a spatial mismatch is Brasilia, a once little-know tropical forest in the hinterlands of Brazil to which, in 1960, the national government moved from its previous home in the world-famous coastal metropolis of Rio de Janiero. There are other examples: in 1908 Australia created a planned inland capital named Canberra to counterbalance coastal Sydney and Melbourne. Pakistan thrust its capital from coastal Karachi to interior Islamabad in 1960; Belize moved its government from coastal Belize City to interior Belmopan in 1970; Nigeria moved its capital inland in 1991, as did Kazakhstan in 1997 and Myanmar in 2005. In some cases, the moves benefit the greater good of the country; in others, they benefit only some. Harvard researcher Filipe R. Campante points out that forward-thrust capitals spatially separate civil servants and the citizens they’re supposed to serve, and can make government “less effective, less responsive, more corrupt and less able or willing to sustain the rule of law.”

Postcolonial North America presented a good a set of circumstances for forward-thrust at the national scale. While neither Washington, D.C. nor Ottawa represent pure examples of the tactic, it’s worth pointing out both cities were products of top-down geopolitical decisions rather than bottom-up economic geographies, and, as capitals, both effectively shifted power away from big old ports (New York and Philadelphia in the U.S; Montreal and Quebec City in Canada) and toward less-developed areas.

The South presented even better habitat for forward thrust. Most Southern states developed predominantly from the outside in, starting with coastal or riverine settlements such as Charleston, Savannah, Pensacola, Mobile, Natchez, New Orleans, and Galveston. All at some point were primate cities as well as capitals of their respective political jurisdictions (states, colonies, or in the case of Galveston, a republic). Today, only one retains the rank as largest city in the state—New Orleans, and barely—and all have relinquished their capital status to interior locals: to Columbia, Atlanta, Tallahassee, Montgomery, Jackson, Baton Rouge, and Austin, respectively. To be sure, other factors were involved in these shifts, and none present so fine a case study of forward-thrust as Brasilia. But all of them ended up spatially reshuffling political power—and the attendant jobs, houses, roads, commerce, and culture—in the same coastal-to-interior, larger-to-smaller, urban-to-rural, and richer-to-poorer direction as the examples cited earlier.

Louisiana offers a case study. New Orleans in the early 1800s grew from a colonial orphan with a population of only 8000 to, by 1840, the largest city in the South and third largest in the nation. It ranked as Louisiana’s economic, cultural, and political epicenter, despite that it was tucked deep down in the southeastern corner of an overwhelmingly rural state. In every way except the literal, it lay closer to New York than to Natchitoches.

Those incongruences laid the groundwork for discontent, and when time came in 1845 for state representatives to rewrite the state constitution, their differing country-versus-city interests came into relief. One way to rebalance power, delegates decided, was to lower New Orleans’ number of seats in the state senate. Another way was to relocate the legislature and governor out of the city to somewhere farther inland, into the country.

The “country argument” held that the very nature of a large metropolis unfairly advantaged its denizens to convene and lobby for their city’s interests, and to shunt to the state any improvement projects they desired but did not wish to fund.

The “city argument” countered that all the resources needed for governing, from adequate meeting spaces to printing resources to support expertise in the form of lawyers, advisors, and clerks, could be more readily found in a booming city of over 100,000 than in outlying hamlets.

Those on the country side, who like many rural Louisianans today tended to look askance at notoriously libertine New Orleans, responded by pointing out how the many insalubrious temptations of “the Great Southern Babylon” might distract elected officials from tending to the solemn business of government.

What won the country argument was a powerful lobby on its side: affluent, urbane planters of sugar cane, cotton, rice, and the other agricultural commodities on which the wealth of New Orleans depended utterly—far more than it needed the apparatus of state government. In essence, city delegates realized they had more of a stake in their country cousins’ argument than they had in a handful of government jobs.

Delegates thus agreed to move the state capital out of New Orleans by at least 60 miles, enough to keep the urban influences to a minimum. In 1848, the Louisiana legislature officially relocated itself and the home of the governor to Baton Rouge, a city that, in 1840, was two percent the size of New Orleans.

Today Baton Rouge is 62 percent the size of New Orleans, and its parish population exceeds that of Orleans by 20 percent. The change has many explanations, of course, but a major one on the Baton Rouge side of the equation is the stabilizing presence of state government—the essence of forward-thrust.

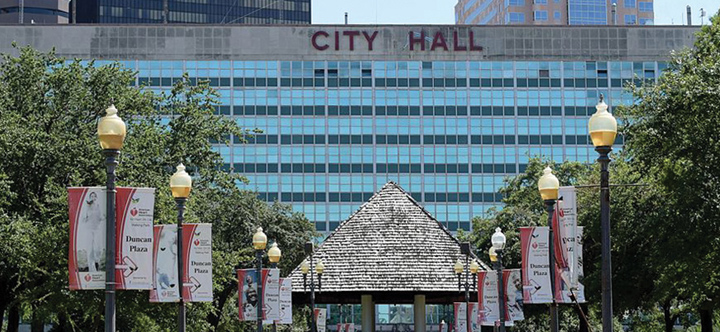

The Greek Revival Gallier Hall (1851), at top, was replaced by the modernist new City Hall in 1957 as the seat of New Orleans government.

Variations of forward-thrust may be found in municipal history as well. When Mayor deLesseps “Chep” Morrison relocated City Hall from its cramped confines at Lafayette Square to a spacious modern Civic Center in the late 1950s, he did so in part to spread downtown development into a previously poor “back-of-town” neighborhood (which happened to be Louis Armstrong’s birthplace). Not coincidentally, Morrison’s new City Hall complex reflected the same bold architectural Modernism under construction at the same time in Brasilia.

As for adjacent jurisdictions, Jefferson Parish keeps its seat of government in the West Bank city of Gretna in large part to counterbalance the economic and demographic preponderance of East Jefferson. Farther downriver, Plaquemines Parish government seated itself in tiny Pointe a la Hache to help keep its sparsely populated East Bank relevant to the larger West Plaquemines population. But after the courthouse was torched by arsonists in 2002 and government moved across the river to Belle Chasse, neither Pointe a la Hache nor East Plaquemines were ever quite the same.

St. Bernard Parish, meanwhile, evidences what happens when forward-thrust goes in the opposite direction. The parish courthouse, once located in the rural eastern flanks of the parish, moved in the 1930s to Chalmette where industry and urbanization from nearby New Orleans had been spreading. The country-to-city shift has left rural eastern St. Bernard nearly as depleted of resources as East Plaquemines, while the urbanized western part of the parish claims the lion’s share of demographic, economic, and political activity.

Looking over our region and state, it is striking how much of the cultural conversation we engage in today has been influenced by these political-geographical decisions. Much has been written about the cultural chasm, for example, between southern and northern Louisiana, coast and interior, city and country; between notorious New Orleans and liveable Baton Rouge, rowdy Natchez and staid Jackson, gracious Charleston and Savannah and modern Columbia and Atlanta.

Whether President Fernández de Kirchner convinces Argentines to thrust their capital inland remains to be seen. But if she does, expect a comparably interesting case study of the intersection of political and cultural geography.

——-

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Bienville’s Dilemma, Geographies of New Orleans, and the newly released Bourbon Street: A History (LSU Press, 2014). Campanella may be reached through richcampanella.com or [email protected] and followed on Twitter at nolacampanella.