Spring 2022

I’ll Play with You

Ruby Bridges is the 2022 LEH Humanist of the Year

Published: February 28, 2022

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Photo by Akasha Rabut

Despite all Bridges saw in 1960, and all she’s seen since, her work with school-age children in the United States attests to her belief that racism is not a permanent condition, and to her certainty that she wouldn’t have had any problems with the white children she eventually encountered at Frantz if their parents hadn’t ordered them to ostracize her.

Her young audiences have enough of a moral compass to know right from wrong, which underscores her point that her white classmates would have done right if their parents hadn’t corrupted them.

“I travel all across the country. I see them. They’re Black, they’re white, they’re Asian, they’re Hispanic. They all look at this story and they relate to the child and the loneliness and the fact that somebody bullied them, somebody didn’t want to play with them. Just the other day, I was doing a Zoom. A little boy said, ‘I’ll play with you. I’ll be your friend.’”

Federal marshals escorted Bridges into Frantz in the Upper Ninth Ward the same morning they escorted three other Black girls—Gail Etienne, Tessie Prevost, and Leona Tate—into McDonogh 19 in the Lower Ninth Ward. Two other Black girls were supposed to start Frantz with Ruby, but their parents decided against sending them. So, unlike Gail, Tessie, and Leona—who had one another—Ruby had only herself. And the iconic black-and-white footage of her entering Frantz presents her as a solitary Black figure against a white-hot backdrop of hate. She was one of four in New Orleans. But she was one of one at Frantz.

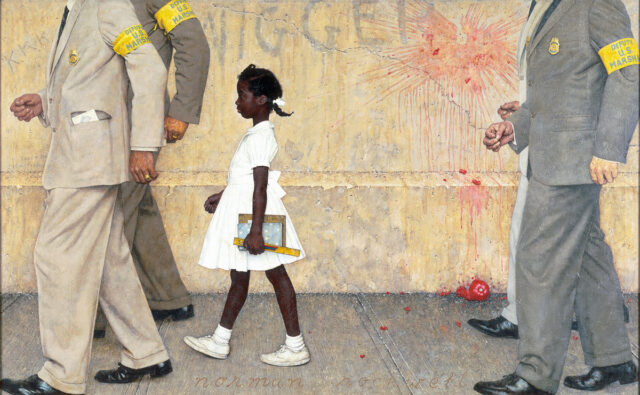

Perhaps even more iconic than the footage of little Ruby in patent-leather shoes and bobby socks is the 1964 Norman Rockwell painting inspired by that scene. The erstwhile illustrator of anodyne Americana presents in that painting a menacing America whose hatred requires a little Black girl on the way to school to depend on the protection of law enforcement. Even so, that painting, The Problem We All Live With, which depicted the remains of blood-red fruit that have been hurled at the child and the word “nigger” scrawled on the wall, showed only a mere glimpse of the evil and hatred Bridges saw every day entering and exiting Frantz.

On November 16, 2021, sixty-one years and two days after her historic walk, Bridges, in a virtual interview, discussed her frustrations at the problem we still live with, specifically the awfulness of parents bequeathing their bigotry to their children and the disingenuous mislabeling of critical race theory that has made her books, which promote racial harmony, a target for removal from school library shelves.

“I know that it’s us,” she said of the stubbornness of racism, “that we pass it on, and we keep it going, and it’s very disheartening. And I just think it’s a shame that our kids really feel the brunt of this.”

Bridges says adults often describe her six-year-old self as brave for integrating Frantz. But she says she wasn’t brave; she was innocent. She didn’t fully comprehend the magnitude of the hatred the segregationists had for her and the new American moment she represented—thus her initial belief that the screaming white people outside Frantz had gathered for a Mardi Gras parade. As an adult, she’s choosing to work with children who are as innocent as she was.

“They come into the world with a very unique gift, and that is a clean heart,” Bridges said. “That is the way I believe the Lord sends us into this world. I felt a sense of responsibility as a six-year-old, and that six-year-old is still in me to catch another six-year-old and explain to them that racism has no place in your heart and in your mind. That if we bring those babies together, put them in an environment together—they will get along.”

If you tell Bridges that’s a hopeful message in what seems like such a cynical time, she’ll agree. The mood in the country, she said, is “very cynical. And I cannot sit here and say to you I don’t see it. I am, just like probably most people, very disheartened by it. But I also know we cannot be a hopeless people. We cannot look at what we see now and get so discouraged that we don’t keep moving forward and keep fighting.”

Bridges has been named the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities’ 2022 Humanist of the Year for her lifetime of work as a civil rights advocate, activist, educator, and founder of the Ruby Bridges Foundation. She’s also being honored for her work as an author. In 1999 she published an autobiographical account of her time at Frantz called Through My Eyes. In 2016, she published a Scholastic Reader called Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True Story, and in 2020, after Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd by keeping his knee on his neck, she, the mother of a murdered son, published This Is Your Time, a hardbound letter to children that became a New York Times bestseller.The LEH honor is especially meaningful, Bridges said, because she has often felt she is more appreciated outside Louisiana. “I am very humbled and grateful. You know there’s a saying that you’re never a prophet in your own backyard.”

There’s a Ruby Bridges Elementary School in Alameda, California, and a Ruby Bridges Elementary School in Woodinville, Washington, but none in Louisiana where, as she points out, “you have to be dead to have a school named after you.” The bronze Ruby Bridges statue, which was unveiled outside William Frantz on the fifty-fourth anniversary of her enrollment, originated in California, where Oakland sculptor Mario Chiodo created her likeness as part of a larger work called Champions of Humanity.

Bridges believes that but for the advocacy of the Ruby Bridges Foundation, Frantz would not have landed on the National Register of Historic Places, and local and state school officials may have let the building be demolished. Other conflicts regarding how she, Frantz, and the integration of New Orleans’s public schools should be remembered have left her convinced that some people think she’s selfishly seeking glory.

“Don’t get me wrong, there’s people all over the city and state that embrace me, celebrate me. They did when I was six. They still do.” But others, she said, “I think they feel like I’ve gotten too much recognition. And I don’t know what that’s about, where it comes from. There’s enough ills to go around for all of us, you know? Really. Pick one and run with it. Regardless of what they may think, that’s what I did. I picked one. And I’m running with it.”

To hear Bridges say that she picked hers will surprise those who’ve assumed her issue was assigned to her by her parents when they switched her out of her all-Black school and sent her to an all-white one. But her sense of agency stems from what happened afterward. Bridges was not known from that day forward as the little girl who integrated Frantz. The truth, she says, is that she and the 1960 integration fight were quickly forgotten.

“Nobody knew who I was,” she said of the next eleven years in public school. “When I showed up to school for second grade, there were no federal marshals. There were no crowds outside. Wasn’t like my parents are really talking about it—because there was a lot of tension in the household.

“Once that year was over, it was over. I remember going back for second grade, running right back to that classroom that I occupied alone with my teacher—and it was no longer my classroom. It was another teacher.

“It was a full class of kids, both Black and white. I was being taught by one of the teachers who had refused to teach me the year before. It was like it never happened. And it just really bothered me. It was like that whole year, wiped away. And it wasn’t like I could go back in a book and find the story or answers to my own questions: Why me? How did it happen? Where did the teacher go? Nothing. So, nobody really knew who I was when I was in school because they would have been the same age as me.”

When I suggested her classmates didn’t know her story because they were too young to read the newspapers she said, “What I’m also trying to say is that it wasn’t really in the newspapers.” It was basically a 1960 story, she said.

“You have to understand here in the city, it wasn’t like people really wanted to remember it and talk about it, because it was such a black eye.” Her family did keep newspaper clippings and letters of support from across the world, but Hurricane Betsy destroyed them.

“Nobody really in my high school knew who I was—or junior high. The only people that really knew were [Gail Etienne and Leona Tate]. We all graduated from the same high school together. But none of my friends knew.”

“It bothered me because it didn’t seem important. It felt like it was important to me. But it didn’t feel important to anyone else.”

After the segregationists forced her father’s firing, longshoremen on their way to the river would routinely leave money to help the Bridges stay afloat, and they’d tell the family that the money was meant to help them resist folding under the pressure. The longshoremen’s help was one of the ways Ruby knew what she was doing mattered in her neighborhood.

But the Rockwell painting, which she saw years after its publication in Look Magazine, was her first indication that she had done something that mattered outside her neighborhood. “I was doing an interview. And the reporter said, ‘You realize that this is you. This depicts your walk.’ And at that moment, it helped me to understand that this wasn’t something that just happened in my community and on my street. Regardless of the fact that no one really wanted to talk about it and that it was kind of swept under the rug, here it was. It actually changed the face of education across the country. It helped me to understand who I was and that I had a mission, you know, and it was up to me to step into that.”

Because Bridges aims to prevent children from succumbing to racial bigotry, it’s especially galling that conservatives misidentifying and misrepresenting critical race theory and wielding it as a wedge issue are trying to stand between her and children. This Is Your Time, Bridges’s new epistolary work, was one of 850 books Texas Representative Matt Krause wanted investigated and considered for removal in October 2021 on the assertion that they “might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress.”

In November, a group called Moms for Liberty, a name that sounds like it was yanked from an Orwell novel, tried unsuccessfully to have the Tennessee Department of Education declare certain books inappropriate for second-graders. Among them were Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True Story and The Story of Ruby Bridges by child psychiatrist Robert Coles, who volunteered to counsel Bridges and her family during integration. (Coles directed all the royalties from the book to her; the funds helped her establish the Ruby Bridges Foundation.) Moms for Liberty also wanted to “protect” second-graders from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

“My first thought was you gotta be kidding me,” Bridges said. “My books really lift both Black and white who really supported me. And so why would you be attacking me for telling the truth?”

“My grandmother used to say, ‘Honey, child, you won’t be able to outrun your blessing!’ Which, I feel like that sometimes. But, then again, it’s also a curse, you know? Just the heaviness of it: people still picking on you for whatever the reason is. If there’s any book that is about uniting us and bringing us together, it’s mine.”

In November, a group called Moms for Liberty… tried unsuccessfully to have the Tennessee Department of Education declare certain books inappropriate for second-graders. Among them were Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True Story and The Story of Ruby Bridges by child psychiatrist Robert Coles, who volunteered to counsel Bridges and her family during integration.

Bridges’s adult activism began at Frantz after her youngest brother, who lived in the Florida public housing project and struggled with drug addiction, was murdered, leaving behind daughters who attended the same school their aunt had integrated.

“When I took them into my house, I had to then drive them back to Frantz school every day. And that’s when I saw things that bothered me. The school was crumbling. Kids were actually urinating in a hole in the floor. The principal that was there was doing everything she could to teach them. [But] the enrollment was going down.”

There was also no evidence that the school had once been all white, or that white children ever attended.

“I felt like that was my responsibility,” Bridges said, not just to volunteer at the school but to preserve the building and build up the surrounding area. “I’d gone to Little Rock. [I] saw what they had done with Central High School and how it changed the whole neighborhood.”

At one point, when the Orleans Parish School Board / Recovery School District was selling off moldering buildings post-Katrina, Bridges imagined Frantz as a site for the yet-to-be-built Louisiana Civil Rights Museum, which the Louisiana Legislature had voted to establish in 1999.

But the school was eventually remodeled and reopened in 2013 as another school: Akili Academy of New Orleans, a charter school operated by Crescent City Schools. According to the school’s website, elements of the building “were restored to their original appearance in order to maintain the historical integrity” of Frantz. As importantly, “Room 2306 serves as the ‘Ruby Bridges Room’ with period furnishings and decor in honor of Mrs. Bridges’s brave contributions to society.”

According to the most recently published data, the Louisiana Department of Education considers Akili a D-rated school. Demographic data reported by LDOE indicates that the school has only two white students.

In print, in film, and in news stories, the story of Ruby Bridges is often presented as a mythical quest of David-and-Goliath proportions. There was a dragon called segregation, and a tiny child of six—armed with nothing but a sweet, incorruptible spirit—went forth and slayed it.

But the dragon wasn’t slain. The giant wasn’t felled. Though segregation is no longer the law of the land, for many Black students, especially those who are growing up as poor as Ruby’s family did, it’s just as real now as it was then. Though Bridges’s aim is to teach Black and white children to get along and to eschew racism, Black and white school children throughout the nation are in many cases as separated today as they were in 1960.

So how should we categorize the Ruby Bridges story? A tragedy? A drama? A multi-generational epic? Or does she see it as a fairy tale?“Feels like all of it, to tell you the truth,” Bridges said, before adding: “I believe it’s going to be victorious.

“My teacher [Barbara Henry] says it was a love story. And I understand her feeling that way. Because she did try to keep what was happening outside of that classroom outside. She didn’t miss a day. Being six and knowing she looked exactly like people outside screaming and carrying a baby’s coffin, and yet getting into that classroom with her and having her—as I described it—show me her heart. I knew she looked like them, but I knew, too, she was different. So that shaped me into the person that believes wholeheartedly that racism really doesn’t have a place in the hearts and minds of our kids.”

To say she believes the story ends victoriously points to Bridges’s sense that, at sixty-seven years old, her story is unfinished. What she most hopes for she hasn’t yet obtained. Not only do American schools remain racially divided, but once again she’s observing white people try to block her individual attempt at addressing the problem. But still she moves in the direction of that hope.

“I doubt if I’ll see it myself,” she said. “I’m pretty sure King left here hopeful—or he wouldn’t have been standing on that balcony. But he knew, because he said, ‘I might not get there with you.’ Yeah, I feel that way, too. I may not see it. [But] I feel like I’m answering my call. This is what I am supposed to be doing. And the little six-year-old inside of me is just not gonna rest.”

Veteran journalist Jarvis DeBerry is an opinion editor at MSNBC.com. His previous roles include founding editor of the Louisiana Illuminator and deputy opinions editor, columnist, and editorial writer at the Times-Picayune. He was on the team of journalists awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for its coverage of Hurricane Katrina and the deadly flood that followed. His columns have won awards from the New Orleans Press Club, Louisiana/ Mississippi Associated Press, and National Association of Black Journalists. I Feel to Believe, a collection of DeBerry’s Times-Picayune columns, was published in 2020 by the University of New Orleans Press and has been selected as One Book One New Orleans’s 2022 book of the year.