In Search of a Rosenwald School

Relics of a Jewish philanthropist’s work to further Black education

Published: August 30, 2021

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Story and Pictures by Brian M. Davis

The Mt. Olive Rosenwald School building in Claiborne Parish.

Julius Rosenwald was born in 1862, in Springfield, Illinois, just a few blocks from the home of Abraham Lincoln. This son of German Jewish immigrants worked in his family’s clothing store and, at the age of twenty-eight, married Augusta Nusbaum, whose family also sold clothing. In 1895, Rosenwald acquired a half-interest in Sears, Roebuck and Company and became president of the company in 1908, when Richard Sears resigned for health reasons.

With his business doing well, Rosenwald’s philanthropic giving to Jewish and African American causes increased. In 1910, he issued a challenge grant to planners of a YMCA building for Black men in Chicago. He would provide $25,000 for the construction of similar buildings in any American city that raised an additional $75,000. This offer eventually produced twenty-six YWCA and YMCA facilities for Black people across the nation, including one in New Orleans. When Booker T. Washington visited Chicago in the spring of 1911, Rosenwald hosted a luncheon for him. Rosenwald visited Washington at Tuskegee Institute in the fall of that year and joined its board of trustees in 1912, promoting its virtues to potential donors.

To celebrate his fiftieth birthday, Rosenwald contributed $687,500 to various causes, including a $25,000 gift to Tuskegee Institute. Booker T. Washington reserved $2,800 of the institution’s gift for an experiment to develop a standard of efficient design when constructing schools. This experiment lasted from the fall of 1912 to the summer of 1914, and focused on six rural communities in three Alabama counties surrounding the institute.

By the mid-1910s, six million African Americans were beginning the Great Migration to industrial cities of the north to search for a better life, following decades under Jim Crow laws. Without outside influence, there was little chance for conditions or opportunities to improve for Black families. A 1916 study by the Department of the Interior, Bureau of Education noted that appropriations for teacher salaries in Louisiana on a per capita basis for white students were $13.73, and $1.31 per Black student. The school term for Black students was typically half that of white students, with Black students receiving three to four months of instruction in a year. School buildings for Black students in the South were rare and primitive in both condition and educational instruction. Disgruntled whites often called for allocations of tax revenues by race of the taxpayers, assuming this would mean prosperity for white schools and little to no growth for Black schools. In actuality, Black taxpayers in Louisiana paid in more than they received back in school funding.

The Julius Rosenwald Fund was established in 1917 and joined a list of other foundations supporting educational advancement for Black people in the South, including the Jeanes Fund (teacher training); General Education Board (helped with all aspects of public schools); Slater Fund (industrial training, high schools and colleges); and the Phelps Stokes Fund (studies on which to base improvements). Rosenwald’s gifts would again be in the form of challenge grants to communities, typically one-third of the cost of the building. The grants would provide an incentive for local support from Black communities, white communities, and school boards. This teamwork would show a common interest to advance educational opportunities for Black children. Community members could donate time, labor, money, or materials to help meet the required match. The new school buildings would encourage further advancements in the educational system and add a valuable facility to a school board’s roster with a small investment of public funds. This experiment also showed the need for expert oversight and coordination, to ensure that standards were upheld for the betterment of their communities.

The first plans for what would become Rosenwald Schools were developed by Robert R. Taylor, staff architect and director of industries at Tuskegee Institute. He was the first African American student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he earned his architectural degree in 1892. Clinton J. Calloway became chief administrator of the building program and worked with Taylor to revise and develop additional plans for school facilities.

“Rosenwald School” was first used in internal correspondence by Tuskegee Institute, to distinguish between their various school programs and funders. The term quickly came to mean a public-school building for African American students that met modern standards.

At the urging of Booker T. Washington, designs were intentionally kept modest, so the new Black school would not outshine the existing white school in the communities of the Jim Crow South, risking envy and possibly arson. This had been the fate of the Strange Industrial School, near Vernon, a small village in Jackson Parish. Several weeks after public notices were posted in the vicinity of the school to cease operations, the school, employing seven teachers and serving over two hundred students, was torched in May 1918.

Sanitation, lighting, and ventilation were important design considerations. Standards covered all aspects, from selection of a site and orientation of the building to site plans for recreation and gardening. Curricula included standards for the time as well as basic agricultural and homemaking skills. A trademark of Rosenwald Schools is the use of “batteries” of four to seven double-hung sash windows to maximize natural light and ventilation. Roofs were typically hipped or gabled, and entrances were usually sheltered by an overhang or recess.

Most of the 5,358 Rosenwald Schools constructed between 1912 and 1932 throughout fifteen southern states were either one-teacher or two-teacher facilities. The Julius Rosenwald Fund supported the construction of 395 schools in Louisiana. It was common to locate the school next to the church, at the center of rural African American communities. Many Rosenwald Schools were used for public education until the 1970s, when Louisiana’s school system was integrated. While some were repurposed for community functions, moved for private use, or maintained by adjacent churches, the majority were demolished or suffered demolition by neglect.

Between 2002 and 2017, the National Trust for Historic Preservation operated the Rosenwald Schools Initiative from their Charleston regional office. Project leaders Katherine Carey and Tracy Hayes provided technical assistance, workshops, grant opportunities, and most importantly, networking for those trying to save Rosenwald Schools and their stories. Lowe’s Home Improvement Stores has been a major sponsor of the initiative, donating more than $4.5 million to save forty Rosenwald School buildings. It is estimated that less than 12 percent of the original buildings supported by the Rosenwald Fund still remain.

Four Rosenwald Schools in Louisiana are listed on the National Register of Historic Places: Beauregard Parish Training School in DeRidder (listed in 1996); Plaisance School in St. Landry Parish (listed in 2004); and Community Rosenwald School and Longstreet Rosenwald School in DeSoto Parish (listed in 2009). Kathe Hambrick, who has researched Rosenwald Schools for the past twenty-six years, was instrumental in moving one from the east bank of St. James Parish to Donaldsonville in 2001, for the River Road African American Museum (RRAAM). That organization received a $300,000 grant from Shell Oil in 2020 to rehabilitate the facility as the RRAAM Rosenwald School for Education, Culture and History.

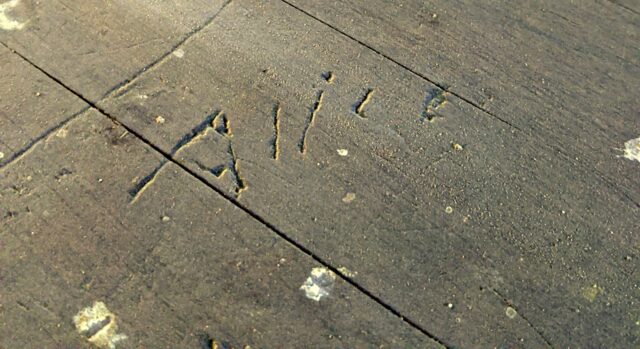

In June 2020, Vince Ory, with the Claiborne Parish Library, and Beverly E. Smith contacted the Louisiana Trust for Historic Preservation to say that they discovered what may have been a Rosenwald School. Further research confirmed that it was the Mt. Olive Rosenwald School, constructed in 1920, at a cost of $3,600. The local Black community provided $1,500; Rosenwald Fund, $1,200; and the Claiborne Parish School Board provided $900 towards construction. Parishioners of the adjacent Mt. Olive Missionary Baptist Church maintained the building after the school system was integrated and are responsible for the building surviving to this day. In recent years, portions of the metal roof have become damaged, allowing rot to occur. Little else has changed in the building over the past century.

Northwest Louisiana had the highest concentration of Rosenwald Schools in the state. Caddo Parish led with thirty-seven schools, followed by Claiborne Parish (thirty-four), Bienville Parish (twenty-four), and Webster Parish (twenty-three).

News of the Mt. Olive Rosenwald School inspired the Louisiana Trust to begin an inventory of original buildings constructed using the Rosenwald Fund. Goals include mapping schools’ locations, identifying which original buildings remain, and assessing their needs in order to assist in saving them. Some school buildings constructed with Rosenwald Funds were replaced by more modern buildings as the number of students increased. Other public schools may have been constructed using the plans and elevations of Rosenwald’s Community Schools, but were not funded by the program. These plans may have been readily available in the school board office and would have facilitated construction without the need to hire an architect for the design.

In addition to school buildings, the Rosenwald Fund supported construction of thirty-one teacher residences and nine shop buildings in the state. Nearly half of the teacher residences in Louisiana were constructed in Claiborne and Bienville Parishes, with nine and four teacher residences, respectively. The residences often contained two or three bedrooms, a living room, kitchen, bath, and covered porch. One has been identified in Claiborne Parish, at the site of the Liberty Hill School. Although the school building has been lost, the teacher residence remains, in a deteriorated state.

On January 13, 2021, President Biden signed The Julius Rosenwald and Rosenwald Schools Act of 2020 into law. This instructs the National Park Service to conduct a special resources survey of sites associated with Julius Rosenwald and Rosenwald Schools for an eventual multi-site national park. This would be the first national park honoring a Jewish American.The impact of Booker T. Washington’s idea and Julius Rosenwald’s philanthropy on African American advancement in the twentieth century is monumental. What began as challenge grants to communities for construction of YMCA and YWCA facilities grew to 5,358 Rosenwald Schools in rural corners of the South. The Julius Rosenwald Fund supported Black colleges, medical facilities, and fellowships for hundreds of students (Black and white) in nearly every field imaginable at the time. Black high school enrollment in the South increased from a few thousand students in 1920 to approximately 125,000 in 1931.

If the national average holds true, Louisiana should have approximately forty-three Rosenwald School buildings remaining. To date, the Louisiana Trust has identified nine and mapped the former location of one hundred schools more that have been lost. The search continues to compare historic topographic maps and satellite imagery, travel backroads, and interview former students and their families in an effort to rediscover and preserve this part of Louisiana’s diverse culture before it is lost.

For more information on Louisiana Rosenwald Schools or to submit information or stories about a school, please visit lthp.org/rosenwald-schools.

Brian M. Davis is executive director of the Louisiana Trust for Historic Preservation. Based on his family farm in Ouachita Parish, he connects the dots with preservation projects in all 64 parishes.