King Crude

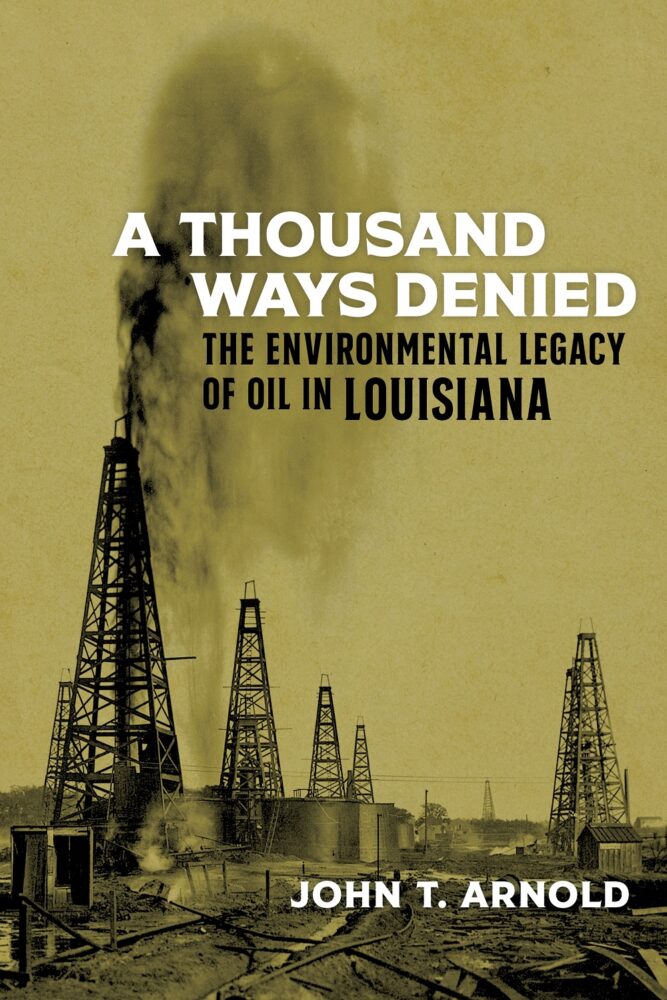

A review of A Thousand Ways Denied by John T. Arnold

Published: November 30, 2020

Last Updated: February 28, 2021

LSU Press

The conflict between conservation and extraction is most dramatically illustrated by conflicts between the oil enterprises and oystermen. Like oil, oysters “long served as a cultural and economic staple for Louisiana” dating to the early nineteenth century. By the start of the twentieth century, state officials worried about overharvesting, and in 1902 organized the Louisiana Oyster Commission “to protect, encourage, regulate, and develop” the industry. The new commission helped oystermen thrive and made Louisiana one of the country’s leaders in oyster production into the early 1930s, when the oil and oyster industries collided. Oystermen hauled up dead oysters in huge numbers. Spoiled oyster habitats endangered longterm profits.

When a state biologist studying oyster habitats in the mid-1930s concluded that the oil industry had polluted oyster beds, it set off a series of court cases forcing corporate remuneration and leading to state enforcement of pollution regulations, but inconsistent enforcement and ongoing battles with oil representatives meant that by the end of the 1950s, oyster habitats faced serious damage. With profits at stake, oil companies had responded with their own scientific studies. As Arnold succinctly puts it, “Industry was using science to create a new storyline.” Oil companies expanded operations in the marsh and continued to kill oysters. He notes, “despite the physical changes wrought upon the landscape, despite the consequential shifts in the ecological character of entire basins and the entire coastline, despite the state’s undeniable awareness of industry impacts, and despite…bold efforts to confront industry and prevent future damages, nothing changed.”

Oysters and those dependent on them were only one casualty of oil’s dominance. In the battle between the oil industry and its economic potential on the one side and environmental conservation and destruction on the other, Louisiana, sadly, often sided with economic promise, which has had lasting environmental consequences. Oil companies continued to dump oil-field waste into freshwater streams and pits. Even “documented violations went unpunished and economics carried the day in the face of increasingly evident environmental damages.” Arnold expertly outlines the court, legislative, and regulatory battles that allowed for delays in meaningful action. He details how oil company waste “damaged crops, timber, and freshwater, and interfered with other land uses.” And notwithstanding growing state and national environmental awareness since the 1970s, the industry faced few setbacks. Over time, Arnold shows, state regulators chipped away at the mostly unchecked power of oil companies even as they continued apace under an industry-friendly state enforcement regime.

Arnold carefully walks readers through the complex and interlacing reasons for coastal land loss and documents well the struggles regarding oil industry accountability among state legislators, state regulators, and oil company representatives. In all, Arnold reports, Louisiana lost nearly a quarter of its land between 1932 and 2010. He shows how the state has worked to deal with the loss since 1989 by dedicating a portion of the oil and gas severance tax to coastal restoration. Various state and federal projects in the following decades sought to manage and rebuild coastal wetlands. In the process, Arnold reports that Louisiana “dedicated 84 percent of its restoration monies to remedying damages caused by oil and gas operations.” But repairing damage is not all the state has done; these efforts also “served to protect vital energy infrastructure.”

In Louisiana, oil remains both an economic force and an environmental problem, particularly along the coast. As Arnold argues, private conservation groups and landowners have worked to mitigate industry harms, but oil companies are far too powerful for private interests to combat without real government intervention. He appeals to those with the power to act to consider what history has to teach us about the industry’s harms. Let’s hope the right people read it.

Chad H. Parker is department head and associate professor of history at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette where he holds the Jamie & Thelma Guilbeau Endowed Professorship in History. He is the author of Making the Desert Modern: Americans, Arabs, and Oil on the Saudi Frontier, 1933–1973.