Louisiana as Scholarly Inspiration

The sojourn of Élisée Reclus

Published: August 31, 2023

Last Updated: November 30, 2023

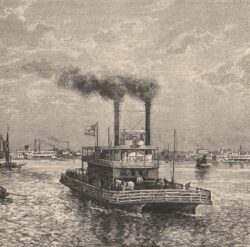

Antiqua Print Gallery / Alamy Stock Photo

An engraving of a steam ferry on the Mississippi River from the first edition of Reclus’s The Universal Geography.

The grand tour tradition rested on the notion that travel was educational, that the experiential was uniquely influential, and that ideas were portable. Much of Neoclassicism, as manifested in architecture, art, and other humanities fields, came courtesy of grand tours of the ruins of ancient Greece and Rome, just as Romanticism and Orientalism later arose from travels throughout the Mediterranean and the Mideast. The grand tour tradition also laid the groundwork for economic expansion and cultural appropriation, not to mention military adventurism, imperialism, and colonialism. Travel, after all, is influential.

As new societies formed across the Atlantic Ocean, European intellectuals expanded their itinerary to include booming cities throughout the Americas, particularly ports. New Orleans, largest city in the South and busiest port in the region, became a must-see stop. You could sail here directly from overseas, else “coastwise” from Charleston and Savannah to Pensacola and Mobile, or take a steamboat down from Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Memphis. There was much to contemplate here: a Franco-Hispanic Afro-Caribbean outpost that became an American city; a polyglot, a Babylon, and a necropolis; a society of slaves and a marketplace of human bodies; an entrepôt between hinterland and foreland; and an experiment in delta urbanism that seemed to get by through brilliant improvisation.

Visitors did not necessarily perceive themselves as being on traditional grand tours, as few expected to see anything “grand” here, and most endured grueling travel and rustic accommodations. Still others were not touring at all, but rather pursuing personal opportunities or taking political exile. But many wrote down what they observed, and many published what they wrote. Some struck tones of moral judgmentalism or cultural condescension, while others betrayed grudging admiration or gleaned intellectual inspiration.

Think of how many great minds came to Louisiana, however briefly, and made from their local experiences lasting contributions in academic disciplines. Benjamin Latrobe in architecture. John James Audubon in ornithology. Alexis de Tocqueville in political science. Harriet Martineau in sociology. Charles Lyell in geology. Walt Whitman in poetry. Frederick Law Olmsted in landscape studies. Lafcadio Hearn, William Faulkner, and Tennessee Williams, among many others, in literature. Some passed through on their version of a grand tour, while others lived here briefly. But the intellectual influence of their time in Louisiana endures to this day.

This being a column on geography, I focus on one erudite visitor regarded as a founder of the modern academic discipline of geography, as well as an ahead-of-his-time voice on political and social theory. His name is Jacques Élisée Reclus, and his time in Louisiana lasted from 1853 to 1855.

Élisée Reclus was no globe-trotting elite, and anything but an imperialist or government apologist. Born in 1830 to a pastor in southwestern France, the youth initially followed his father’s footsteps to a Protestant seminary, until he had a chance to enroll at the University of Berlin. There he attended lectures by Carl Ritter, an influential figure in the academic discipline of geography, and his interests turned to more earthly affairs.

By the time he returned to France, Reclus had also developed political sensibilities that led him to oppose the coup d’état of Napoleon III in 1851. He fled to England, found work in Ireland, and returned to Liverpool with the hope of making it to New York City. “That failing,” writes the late historical geographer Gary S. Dunbar in a 1982 article, “he managed to gain a berth as a cook on a sailing ship bound for New Orleans. He rationalized that if he were to drown, he would at least drown in warm water, and that he could spend the winter out in the open if necessary in New Orleans.” Now there’s a budding geographer.

As he sailed across the Atlantic and Caribbean in 1853, Reclus observed and documented every element of the changing maritime environments. “Suddenly, it seemed that the color of the water had changed,” he wrote as his vessel crossed the Gulf of Mexico. “Indeed, it had turned from a dark blue to yellow, and I saw a straight line of separation, as if drawn with a taut string.” They were approaching the mouth of the turbid Mississippi in lower Plaquemines Parish. “Then [we] came to a dead halt—[our] hull was stuck in [a] slushy hole of liquid mud”—an apt introduction to Louisiana geography.

After a steam tug freed the hull and his vessel proceeded upriver, Reclus took in every detail of the wild delta, where “the Mississippi resembles a gigantic arm projecting into the sea and spreading its fingers,” and “the land consists only of thin strips of coastal mud . . . endlessly renewed by alluvial deposits.” Amid all the raw nature, he was amazed to see, of all things, an electrical telegraph wire. “Science seems out-of-place in the wilderness of Louisiana,” he marvels, “and this wire that mysteriously transmits thought seemed all the more strange in that it passes above the reeds [of] stagnant marshes and a muddy river. Such is the march of civilization in the United States: here, on soggy ground that is not even part of the continent yet[,] the telegraph is the first work of humans.”

Reclus filled his notes with vivid descriptions of every visible landscape element, so much so that one wonders just how much cooking he got done below deck. According to translations by Camille Martin and John Clark published in Mesechabe: The Journal of Surre(gion)alism (1993–1994), Reclus writes of Plaquemines Parish’s reeds, canebrakes, willows, and marsh; dolphins (“whales”), aquatic birds and wild cattle; swamps of cypress trees with “Spanish beard” (moss); Fort Jackson, plantation after plantation, and lines of magnolia, pecan, and Chinaberry trees fronting rows of sugar cane; and brigs tacking upriver, dodging tugs and other vessels steaming downriver. In St. Bernard Parish he sees “a commemorative column in honor of the Battle of New Orleans” at Chalmette, not yet complete at that time. Finally, he thrills to see a “thick black atmosphere . . . over the distant horizon, and . . . all of a sudden, as we rounded a bend, the buildings of the southern metropolis came into sight”—New Orleans.

So began Élisée Reclus’s two-year Louisiana sojourn, which Dunbar describes as his “longest residence in any place outside Europe,” and one that “had a significant role in shaping his political and social views, as well as in extending his geographical knowledge.”

Much of that influence came while Reclus worked as a tutor for the Fortier family children at Félicité Plantation in St. James Parish, an employment reminiscent of that of John James Audubon, who began his famed ornithological paintings between tutoring lessons at the Oakley House Plantation in West Feliciana Parish. Reclus’s position gave him a close view of the institution of slavery and the people it victimized. “Reclus found slavery utterly repugnant,” writes Dunbar; “he deplored the dehumanizing effects of slavery on the whites, as well as on the blacks.” That did not stop him from indulging in patronizing views of people of African ancestry, even as he later married a Senegalese woman and developed a decidedly critical take on European society. So too were his assessments of what he saw in New Orleans; much of his commentary is witheringly judgmental.

There was much to contemplate here: a Franco-Hispanic Afro-Caribbean outpost that became an American city; a polyglot, a Babylon, and a necropolis; a society of slaves and a marketplace of human bodies; an entrepôt between hinterland and foreland . . .

Reclus’s firsthand descriptions of lower Louisiana’s human and physical geography are as insightful for modern readers as these encounters were stimulating to him personally. In a letter from late 1855, he wrote that he had been “pregnant for a long time with a geographical Mistouflet”—that is, “a lively child,” according to Dunbar’s translation—“that I wish to bring forth in the form of a book; I have already scribbled enough, but that doesn’t satisfy me.” Off he went, to Caribbean and South American ports, on various pursuits that didn’t necessarily pan out. But all along he gathered additional field observations for a professional career as a geographer, while honing a radical political philosophy highly skeptical of governmental power—something surely informed by what he saw of institutionalized slavery in Louisiana.

“Élisée Reclus’s American experiences, in both Louisiana and Colombia, were to provide him with material for most of his early publications,” Dunbar assesses. “He had purchased a notebook from a New Orleans stationer, [in which] he entered geographical information,” much of which appeared in his 1859 article “Le Mississipi, études et souvenirs.” That and other publications earned him a reputation as one of France’s leading experts on the United States during the Civil War—and one of the few supporting the Union cause. His Louisiana work later found its way into his magnum opus, the two-volume physical geography La Terre published in 1869.

Élisée Reclus never returned to Louisiana, but his experiences here, according to Dunbar, “were of inestimable value to him in his formative years,” and as he “settled down in Paris, he began to reap the harvest of the seed that he had sown in Louisiana, [becoming] the most prolific geographer of modern times and a leading figure in the European anarchist movement.” He died on July 4, 1905, though his influence, originating in that sojourn of 170 years ago, lives on today.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Draining New Orleans (LSU Press, 2023), The West Bank of Greater New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, and other books. He may be reached at richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on Twitter.