Latest

Masking the Pain

Social distancing practices recall mourning rituals from an earlier time

Published: May 6, 2020

Last Updated: September 5, 2022

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library

1891 advertisement for women’s mourning clothes and accessories.

May 6, 2020

Over 450 people in New Orleans and 2,000 people in Louisiana have died from COVID-19 as of this writing. Some of us are actively mourning the loss of a loved one. Others are deeply concerned about friends and family members who have been or might become infected. Most New Orleanians and Louisianans are also mourning the culturally rich public events and spaces that make the city and state unique. Recently, leaders and officials have been discussing how and when to safely reopen beloved local restaurants, businesses, and cultural venues. Part of this discussion has centered around the question of wearing masks, and many public health professionals and political leaders are now asking us to cover our noses and mouths when out in public.Accordingly, the creativity and ingenuity of South Louisianans is now manifest on sidewalks and in grocery lines. From the wild-West-robber-style bandanas to the home-sewn, Saints-patterned, and coffee filter-pocketed, masks are now helping community members protect one another from infection. But for many people, the masks can also be frightening and saddening. They obscure facial expressions—including smiles—and muffle voices, making tone and intent difficult to decipher. Yet, the masks have also become, for many, a visible sign of mourning for a sense of normalcy. We are mourning our festivals and crawfish boils, our barbeques and dance halls.

While it is clear that South Louisiana’s cultural practices and traditions are not dead, merely dormant, considering mourning as a process involving uncertainty might help explain what some of us are feeling. When mourning the passing of a loved one, pain often comes in part from the fear of facing the future in their absence, from wondering about what Carnival or Christmas will be like without them. Many Louisianans now confront a similar fear, wondering what our gatherings and events will be like when the public health crisis is over. While the formalized mourning dress of the nineteenth century is no longer common, reflection on this tradition can still show us how clothing reflects the interplay of emotion and culture.

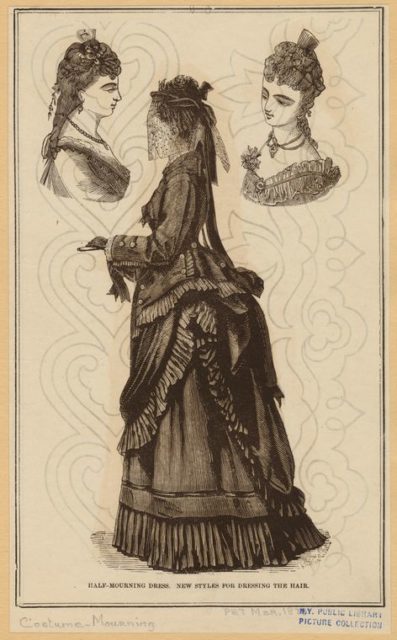

“Half-Mourning Dress: New Styles For Dressing The Hair,” 1873. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library.

In the nineteenth century, industrialization and urbanization enriched the middle and upper classes. Advancements in manufacturing and transportation paralleled the growth of the financial sector, which demanded increasing numbers of men work as professional administrators and managers. Politicians and industrialists celebrated this growing class of professionals for their acquisitive and competitive behaviors in the workplace, while cultural critics reinforced women’s roles as moral and emotional arbiters and exemplars in the home, and times of loss were no exception. For some women, particularly those among the financial and social elite, mourning dress and the ability to adhere to strict rules about its nature and duration represented the depth of their Christian faith and their commitment to honoring the deceased. Those who could afford it would purchase an entire mourning wardrobe, replete with jewelry carved from jet, a deep-black fossil mineral. They might remain in mourning for over two years. A woman who had lost a husband or other immediate family member was expected to wear all black for a year and a day. Acceptable fabrics included crepe or other dull, often itchy weaves unadorned by colored or shiny trim.

Advertisements from the time reflect attempts by clothiers to appeal to these specificities, while advice columnists debated acceptable deviations. For example, after a series of articles discussing clothing fabric and design suitable for the hottest months, the “Questions and Answers” columnist for the August 1891 edition of the Ladies’ Home Journal told Mrs. J.C.D.: “All black means that you can wear any material you like, so that it is black. Your black grenadine would be in perfectly good taste, but you should not carry black bordered handkerchiefs after leaving crape aside. Jewelry is not in good taste, even with all-black….”

Women in full mourning were also generally expected to refrain from excursions outside the home or hosting visitors. When a woman obeying this social stay-at-home order did leave the house, most likely to attend church, she wore a long black veil to conceal the depth of her grief from others. The veil would have covered her hair, face, and torso. After a year and a day of full mourning, women could gradually introduce subdued gray or lavender trim to relieve the severe black.

For mourners these distancing practices could be alienating and potentially psychologically damaging. Expecting women to isolate themselves and keep at more than arm’s length the friends and family best able to help them cope with their grief rendered the ritual of mourning an inordinate burden. Nevertheless, the fact that so many women persevered suggests the power of warp and weft to testify love and care.

The intensity of nineteenth-century mourning dress and expectations for women offers surprising parallels to the use of masks during this COVID-19 pandemic. Then newspapers and ladies’ magazines were filled with advertisements for mourning veils and tips on social customs. Now businesses and entrepreneurs are quickly adapting to demand for masks even as the etiquette of mask wearing has not yet solidified. Social media ads and television commercials tout the fabrics most suitable for mask manufacture, and Etsy crafters are offering mask styles and patterns to satisfy any aesthetic. For those in need, Hanes has donated thousands of masks to multiple parishes. The symbolism of a mask is still being defined—our descendants may see then as markers of fear and uncertainty or of civic responsibility and solidarity. We can only hope that the separation they place between us is only physical, and that we can rely on each other for support, if from a distance.

Robin Runia is Associate Professor of English at Xavier University of Louisiana. Her research explores gender and genre in women’s writing of the long eighteenth century.