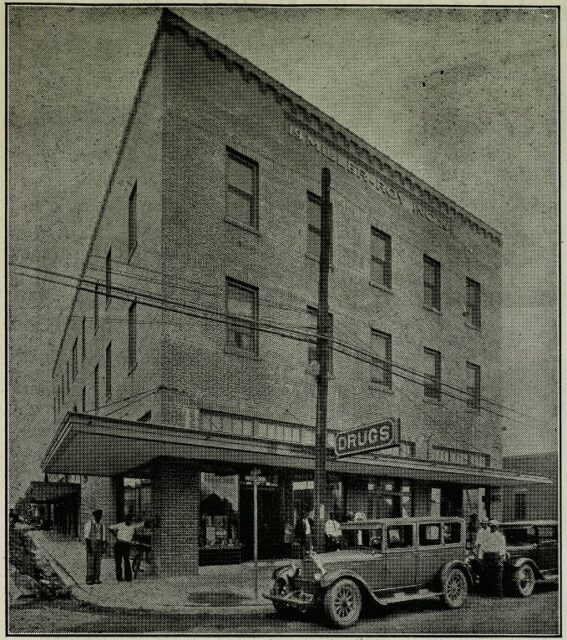

Monroe’s Miller–Roy Building

Chitlin’ Circuit heritage preserved in a mixed-use space

Published: August 30, 2022

Last Updated: November 29, 2022

Photo by Rebecca Mixon

The Miller–Roy Building under repair in April 2022.

For decades the only life in the hollow building had been trespassers (a group I considered joining out of persistent curiosity), neighborhood squirrels and pests, and the seemingly tangible memories of a once vibrant, vital part of the African American community. On that particular April morning, a man in a white hard hat was high in the breezy air near the top of the third floor of the building’s east side, working with a surgeon’s artful touch to revive the original bricks after years of neglect. His coworkers weaved through hallways and up and down staircases carrying steel and wood, nails, bolts, and tools, each with their own artistic contribution to this work of heart. A new structure was being built next door—the Bayou Savoy Building. Right away I noticed subtle but significant elements in the new construction that honor the original design, such as the Miller–Roy’s large arched window mirrored on a smaller scale in the Bayou Savoy Building.

The Bayou Savoy architecture complements the Miller–Roy Building’s refurbished beauty in modest yet substantial ways. When combined with the innovative empowerment plans implemented by community partners, the restoration effort has the potential to be meaningful on a scale similar to when it was built by Drs. J. T. Miller and J. C. Roy in 1929.

Louisiana District 14 State Representative Michael Echols envisioned the project long before the first brick was refurbished.

“It’s probably the most historically significant building in the downtown [Monroe area],” Echols said, “and I initially had started a conversation with the family who owned the property at the time, but it was in a very complex estate, and they weren’t necessarily motivated. [The Miller–Roy Building] was condemned. The City Council had already approved to tear the building down.”

On March 7, 2011, the Miller–Roy Building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Louisiana Trust for Historic Preservation describes the Miller–Roy Building as “a hub for African American social and business life,” and throughout the years, it held many respected businesses and social services. Its status as a historic site was determined based on several factors, including its housing Monroe’s first African American–owned newspaper and several other businesses, such as a pharmacy where the area’s first female African American pharmacist practiced, a dentist’s office, and a barber shop.

The Miller–Roy Building’s third floor housed the Savoy Ballroom, a stop on what was known as the “Chitlin’ Circuit,” performance venues that extended throughout the eastern, southern, and midwestern United States where African American entertainers were welcome during segregation. The ballroom hosted Monroe’s first Mardi Gras, and performers such as Lena Horne, Louis Armstrong, Percy Sledge, Otis Redding, and Billie Holiday graced the Savoy Ballroom with their talents during its heyday.

The building’s historic designation meant the structure could not be demolished, but efforts to restore it to a functional state were continuously met with legal and governmental obstacles until Echols and his partners proposed a plan. According to Echols, previous plans included locating the Northeast Louisiana Delta African American Heritage Museum at the location; however, stakeholders responsible for the museum turned down the concept. Still, Echols continued to believe in the building’s potential.

“There have been a lot of starts and stops for about twenty years, and nothing ever happened,” Echols said. “It is really going to make that a vibrant neighborhood again.”

Echols partnered with his wife Christie Echols, architect of Echo Design and Development, and Ben Marshall, Monroe attorney and owner of Bulldog Title, in the initial phases of the lengthy process. Funding for the revitalization project came from several sources. A $7.1 million Community Development Block Grant and $1 million in National Housing Trust Fund dollars were received from Louisiana Housing Corporation, along with $6.4 million in federal low-income housing tax credit equity and $1.2 million in federal historic tax credit from Hunt Capital Partners. Cedar Rapids Bank & Trust contributed $1.6 million, and $1.3 million in state historic tax credit was received from Enhanced Capital.

Detail from page 57 of a 1942 issue of The Sepia Socialite, a compendium of Black business listings and community news. Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State University.

The Miller–Roy Building features eighteen affordable, one-bedroom, one-bath apartments and a first floor offering community services, such as Ouachita Parish Police Jury workforce development, the United Way of Northeast Louisiana Financial Health Center, and the United Way 2-1-1 information line for social services. The WellSpring will connect the community with services related to counseling, homelessness, domestic violence, youth empowerment, and sexual assault, and the Northeast Louisiana Housing and Supportive Services Corporation (commonly referred to as HOME—Housing Options Meant for Everyone—Coalition) will also partner in the development. Four of the Miller–Roy Building apartments offer permanent supportive housing to people who experience homelessness.

Janet Durden, United Way of Northeast Louisiana (UWNELA) executive director, said the partners work together to “develop an integrated approach to improving the financial stability of Ouachita Parish residents through the Financial Health Center in the Miller–Roy Building. Community members can access a wide variety of services, including income supports, employment and educational opportunities, asset-building services, and more. We are so thankful for the Financial Health Center and the Miller–Roy Building Services.”

According to Kim Lowery, UWNELA director of community impact & organizational strategy, “Research shows that in Louisiana, 891,000 households—51 percent statewide and 53 percent in Ouachita Parish — struggled to afford basic household necessities in 2018. By offering the Financial Health Center in the Miller–Roy Building, we are helping address part of this problem in a convenient location with direct services, such as workshops, training, and advocacy, and indirect services as well, such as 2-1-1 information and referrals.”

According to Lowery, the Financial Health Center offers individualized financial coaching; income tax assistance; and the Heirship Project, outreach, advocacy, and workshops providing education and direct legal services to residents with inherited property and title issues.

Lowery said the Miller–Roy revitalization and the services offered are a “wonderful example of the community giving back” and explained that anyone can access the services. In fact, the goal for the first year of the Financial Health Center is to touch five thousand lives, an impact reaching far beyond the residents of the two buildings.

Having the UWNELA team serve people in the area is not new to the Miller–Roy Building. During the initial phases of construction, a sign likely dating back to the early ’70s identifying Twin City Community Welfare as a UWNELA Partner Agency was still hanging in the building. Lowery said Echols preserved the sign, which can be seen on the first floor of the newly restored Miller–Roy Building to honor a little piece of the building’s legacy.

“We want to empower people to do well for themselves,” Lowery said and described the building as a wonderful foundation to build upon, both literally and historically, and also a blank slate, a space for people who access services to rewrite their futures with help from “community partners who want us all to succeed.”

The two buildings are all about connections. Just as the partners in the Miller–Roy Building’s first floor connect people with community services, gardens, outdoor communal areas, and walking paths connect the structures. As Echols talks about the project, “communal” is a word he often uses. Each floor of the Bayou Savoy Building features a “communal” area where residents can meet or relax in a shared space.

Standing in the Miller–Roy’s arched window on that cool April morning before the buildings opened, I felt those phrases—“resilient” and “stand the test of time”—hang in the air with such meaning. After its thriving early days as a hub of African American community, culture, and commerce, after being condemned and then left in limbo for so many years, the Miller–Roy Building stands as a symbol of resiliency. Today, it has renewed purpose to carry it—and its neighbor, the Bayou Savoy Building—to its hundredth anniversary in 2029 and beyond.

Rebecca Mixon is a dedicated logophile who enjoys talking and meeting people as much as writing and creating. Raising three daughters with her husband Randall and managing a career in healthcare community impact give her plenty of chances to do all of the above.