Mr. New Orleans: Pete Fountain

Published: August 9, 2016

Last Updated: October 4, 2017

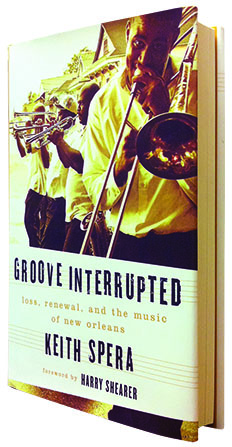

* Excerpted with permission from Groove Interrupted: Loss, Renewal, and the Music of New Orleans by Keith Spera.

In 2000, I encountered Pete Fountain and his good-humored, long-suffering wife, Beverly, in a Biloxi, Miss., casino following a performance by comedian Don Rickles. The famed clarinetist had recently celebrated his 70th birthday. Apropos of nothing, he offered to show me his new tattoo. Beverly rolled her eyes as her husband unbuttoned his shirt to reveal an owl pulling a snake out of his belly button. An owl. Pulling a snake. Out of his belly button.

Beverly shook her head as Pete stood amid the slot machines and retirees, grinning broadly. He said the tattoo had something to do with Native American culture. A more likely explanation is that the notion of getting inked with such a grand design at his age appealed to his still-mischievous sense of fun. That’s all the reason he needed.

Ten years later, I joined hundreds of well-wishers for Fountain’s 80th birthday bash at Rock ‘n’ Bowl, a combination bowling alley/music venue/shrine to New Orleans nostalgia. He had endured some hard years in the interim, thanks to Katrina and assorted physical ailments. He’d lost significant weight; the owl tattoo likely flew a little lower on his downsized belly. But surrounded by family, friends and fans at Rock ‘n’ Bowl, his eyes still twinkled. He bent down to kiss my four-month-old son, Sam, on the head. One day I’ll tell Sam about the time he received a blessing from the merry pope of New Orleans.

![]()

The old man in the checked shirt shuffles past St. Louis Cathedral, the grand house of worship at the heart of New Orleans’ Jackson Square, and ducks into Pirates Alley unnoticed. In the shadow of a banana tree, he opens a black case and carefully assembles a LeBlanc clarinet with

gold-plated hardware. He touches the horn’s reed to his lips.

Pete Fountain recorded 56 albums and been a featured performer on 44 additional albums for a total of more than 100 recordings.

With that, he is anonymous no more. He is Pete Fountain, Mr. New Orleans, briefly restored to his natural habitat. A rough couple of years had left him less steady on his feet. Hurricane Katrina obliterated his beloved 10-acre waterfront estate in Bay St. Louis, Miss.; reduced the three-story, 10,000-square-foot main house, two guest cottages and storage barn to 120 truckloads of debris. Decades of memorabilia, the record of a life lived large in the name of New Orleans — all of it gone.

Aftershocks included quadruple bypass surgery, two minor strokes, and a bout of shingles. Regardless of whether they resulted from the stress and upheaval of the storm, from advanced years, or from a cruel combination of both, the result was the same: his heart now beats to the rhythm of a pacemaker. Words sometimes get lost en route to his mouth; one-liners don’t tumble out quite so easily anymore. Growing old, he’ll tell you, ain’t easy.

Once upon a time, Fountain and Fats Domino were the most famous New Orleans musicians who actually resided in New Orleans. The clarinetist’s two years on The Lawrence Welk Show made him a star. Welk didn’t much cotton to Fountain’s Big Easy attitude, but Johnny Carson did. Fountain made 59 appearances on The Tonight Show, selling his records and himself as the mug and melody of good-time New Orleans. Along the way he entertained presidents and a pope, a jester in the courts of kings.

He and his buddy Al Hirt, a bear of a trumpeter whose dense beard was the ying to the yang of Fountain’s bald dome, defined the city’s nightlife with their respective Bourbon Street clubs. They lived large, laughed loud, and drank a lot. For a generation or two, Fountain was as integral to Bourbon Street as go-cups and strippers.

Pete Fountain’s French Quarter Inn was a popular nightclub located at 800 Bourbon St. from 1969 to 1969, when he moved his operation to 231 Bourbon St.

Closing in on 80, his eyes still danced and his clarinet still sang, but he didn’t visit the French Quarter much anymore. He usually spent the first part of each week at a new house — built a few blocks inland, rather than right on the water — in Bay St. Louis. On weekends he returned to his longtime home in New Orleans’ leafy Lake Vista subdivision, near Lake Pontchartrain.

But on an overcast afternoon in April 2008, he materializes in the Quarter like the ghost of Bourbon Street’s past. The LeBlanc clarinet in his hands survived Katrina because he worked a casino with it a couple nights before his evacuation and set it down near the door of his doomed house. He grabbed the horn on his way out; the instruments he left behind were washed away.

All that is required of him on this day in the Quarter is that he pose for pictures with the clarinet. But when you’re Pete Fountain, you can’t help but play.

![]()

In a town well-stocked with partisan characters, laying claim to the honorific “Mr. New Orleans” is no small affair. But so what if many of his favorite restaurants are outside New Orleans proper in Jefferson Parish? Or that he prefers to watch Saints games at home instead of in the Superdome with the faithful? Or that for decades he spent weekends in Mississippi, in a gigantic house where “you can run around like crazy, and nobody hears you?”

His claim to the title runs much deeper: Pete Fountain is joie de vivre personified. From humble origins — his dad drove a Dixie beer truck — he emerged as the most famous contemporary ambassador of traditional Dixieland jazz. “It snuck up on me,” Fountain once said of fame. “I didn’t look for it. I never did strive for anything. Through the years I just wanted to play. I enjoy playing. When you enjoy playing, and your clarinet is singing, it’s stealing. You feel like, ‘They give me money to do this?’ But some nights when it’s not working, you say, ‘Boy, I wish I had taken over my daddy’s beer route.’“

He idolized the great Benny Goodman and New Orleans clarinetist Irving Fazola, of the Bob Crosby Bobcats. He aspired to replicate the fat, bluesy tone of Fazola and the drive, swing and technique of Goodman. By combining the two, he hit upon a sweet sound all his own.

It was an irate teacher at Warren Easton High School who set Dewey LaFontaine Jr. on the path to glory. One day he was sleeping in class. His excuse was that he worked nights as a musician on Bourbon Street. The teacher asked how much he made. Fountain told him: $150 a week. “He said, ‘I don’t make that — go turn in your book,’’’ Fountain recalled with a chuckle. “He wrote my mother a note saying, ‘Let this boy get some sleep so he can work at night.’“

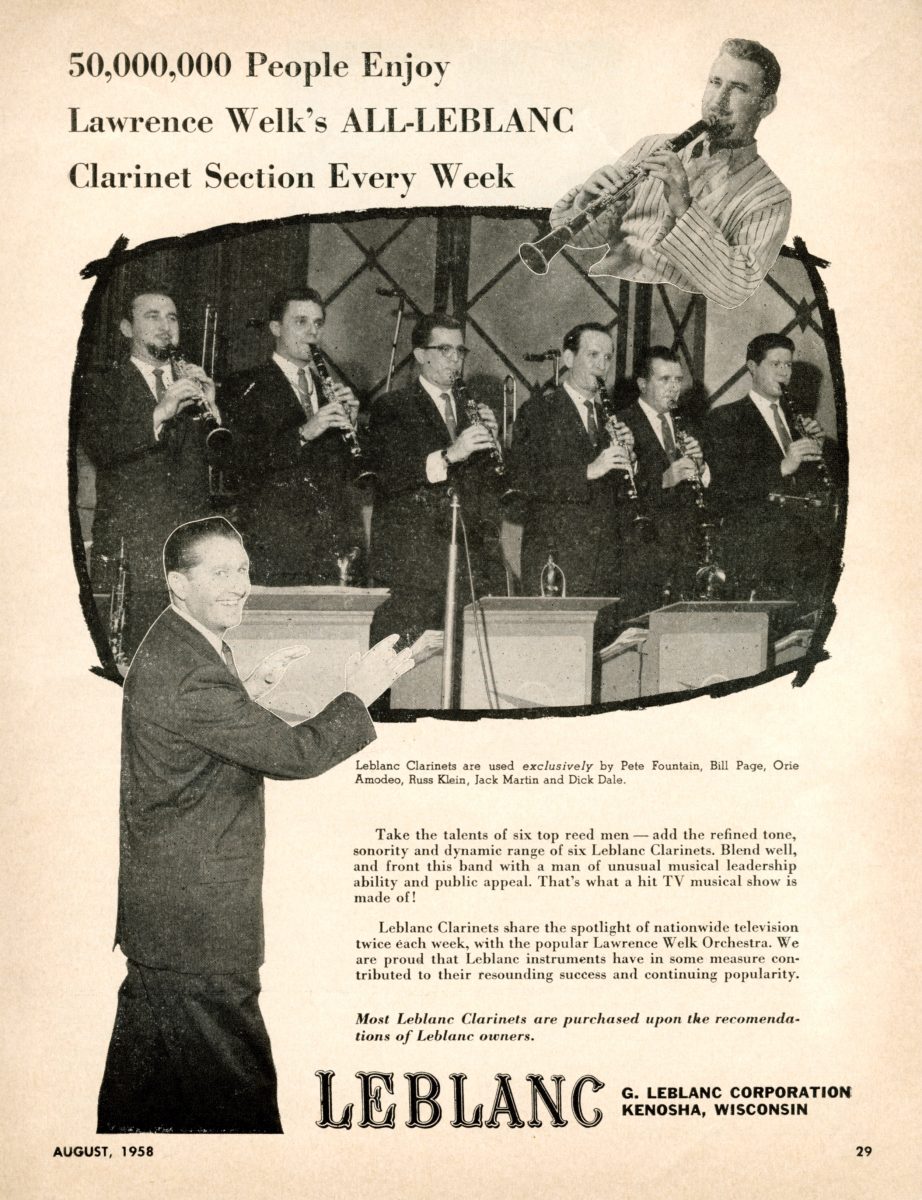

So Fountain, a senior, quit school — although years later Warren Easton officials awarded him a diploma and class ring — to blow his horn full time. His reputation grew, especially during his tenure with the Basin Street Six. In 1957, celebrity big bandleader Lawrence Welk caught wind of this swinging clarinet player down in New Orleans and offered him a job. Fountain accepted, even though the gig required he move to Los Angeles, the first and only time he would live full-time outside the city of his birth.

JIM RASCH / THE TIMES-PICAYUNE

Pete Fountain plays at a club on Bourbon Street in New Orleans, April 1, 1971.

As the featured soloist on ABC-TV’s popular weekly The Lawrence Welk Show, Fountain stepped out in front of the orchestra to accompany the adorable Lennon Sisters’ harmonies on “White Silver Sand.” He squared off with young trumpeter Warren Luening on a hot “Jingle Bells.” He soared through “Tiger Rag” and “My Blue Heaven” as coat-and-tied young men and perfectly coiffed young ladies danced chastely. “Pete, are you all ready? Swing right out,” Welk instructed, and Fountain obliged.

Week in and week out, he conducted a clarinet clinic of exquisite tone and taste. Broadcast in black and white into living rooms across America, he was one of the most visible jazz artists in the world at a time when people still bought jazz albums. Three of his sold more than a half-million copies apiece. Pete Fountain’s New Orleans, a straight-ahead 1959 recording with piano, drums, bass and clarinet, is considered a requisite Dixieland jazz album. “I did 45 albums for one company, and most every one would sell a hundred, one hundred-fifty thousand copies. Which is fantastic. I’d get some fantastic checks, which I blew.”

The dreamy Champagne fantasies fostered by the rigorously conservative Welk did not always abide the Bourbon devil inside Pete Fountain. Welk strictly forbade his musicians to drink on the job. “He kept me sober — damn near killed me,” Fountain complained to me 40 years after the fact. “Every time they make rules to a guy from New Orleans, he’ll break it. Instead of just going to the bar and getting a drink, I’d get a double.“

Pete Fountain received nationwide exposure as a regular performer on The Lawrence Welk Show from 1957-1959.

One night at the Aragon Ballroom in Santa Monica, Calif., Welk discovered Fountain had snuck a nip or two. Determined to teach his wayward young musician a lesson, the taskmaster called for five consecutive songs featuring the clarinet. “He put me in the front, and made me play one after the other, waiting for me to make a mistake. The more I played, the hotter I got. So he finally backed off. He must have thought, ‘This kid can drink.‘“

Fountain initially introduced himself to America in his natural state: receding hairline, thick-framed eyeglasses, a modified chinstrap of a goatee. Welk’s people eventually prevailed on him to ditch the glasses, downsize the chin hair, and wear a toupee. But he was still Pete. As the other members of the clarinet section flipped through playbooks on their music stands, he ogled a Playboy.

In 1959, two years into the Welk gig, homesickness prompted him to quit and move the family back to New Orleans. He bought a handsome home near Lake Pontchartrain and opened his first club at 800 Bourbon Street in 1960. Several years later, he moved to a larger space at 231 Bourbon. Unlike Welk, he did not prohibit his musicians from drinking. He was at the heart of Bourbon Street intrigue and action. “I went to McDonogh 28 [grade school], Warren Easton, and the conservatory of Bourbon Street.”

All manner of dignitary and not-so-dignitary stopped by. “I just sat there with my mouth open, listening to him play,” recalled country music outlaw Hank Williams Jr., a satisfied customer. “I really like that kind of stuff. We sat around the dressing room and shared a little toddy together. It was real special.”

A dispute with his landlord sent Fountain in search of new digs in 1977. The Hilton Riverside was about to open downtown at the foot of Poydras Street, overlooking the Mississippi River. The hotel’s management offered to customize a third-story club for him. Equal parts New Orleans bordello and Las Vegas lounge, the space sported crimson velvet walls, cocktail waitresses, maître d’s who escorted patrons to tables, multi-tiered seating, and red vinyl handrails supported by grapevine wrought-iron posts. At the start of every show, the call rang out, “Ladies and gentlemen, will you please welcome Mr. New Orleans, Pete Fountain!”

Over the years, he made, and lost, multiple fortunes. “I’m a bad businessman. I blew some serious money. I never did gamble, I never did throw it away. Somebody would say, ‘Want to get into the hotel business?’ and I’d go, ‘Oh, yeah, sounds good!’ I bought a hotel, I bought this, I bought that.”

Among his more infamous investments was Peter’s Wieners, a fast-food hot dog stand in Bay St. Louis. T-shirts trumpeted “The Wiener That Puts A Smile On Your Face!” He envisioned franchises mushrooming all over the country, like Wendy’s. Instead, he took a $100,000 bath.

Nostalgia for that idea (and that money) lingered, but he has no use for regrets. “If a frog had wings, he wouldn’t bump his ass. You can’t go if, if, if — it’d make you sick. I say it once in a while, and that’s it.”

The wiener business “was fun. All these things are fun while they last. As long as I can keep tootin’ … The day I can’t keep tootin’, then I’m in trouble.”

Publicity portrait of Pete Fountain from the 1974 World’s Fair in Spokane, Washington.

Beverly, his sainted wife, contributed mightily to the effort to keep him out of trouble. “She should have left me on the honeymoon,” her husband contends. “She raised me — I was her oldest boy.” She mostly raised her three actual children, too, as her husband was often on the road or working late at his club. Or sauced. During the ‘60s, Fountain observed “the whole world going crazy — and I was in there with ‘em.”

He embarked on a decade-long game of chicken with whiskey. He blinked first. “Jack Daniels whipped my butt. I thought I’d beat him, but you can’t beat Jack Daniels. He’s too strong. My wife used to tell the kids I had the flu. Every weekend I had either the Jack Daniels flu, the Taaka flu, or the tequila flu. It’s just one of those things that pass you by. It’s like another life. I’ve gone through three or four lives.”

Those lives got progressively tamer. He eventually handed down the tradition of all-nighters in hotel bars to the younger members of his band, while he turned in early. Onstage, he sipped a mild half-and-half mixture of white wine and Perrier. “Things change. Nothing stays the same. I used to be taller.”

![]()

Instead of a rooster, many New Orleanians awaken to the sound of Fountain’s clarinet on Mardi Gras morning. Since 1960, he and his Half-Fast Walking Club have spent the early hours of Fat Tuesday “tootin’ and scootin’” along the downtown parade route, distributing kisses, paper flowers and jazz to the Carnival diehards who staked out a spot before breakfast. Over the years, “I think we’ve walked from here to Florida,” Fountain said. And that’s definitely Walking Club, not Marching Club. “We can’t march. If we marched, we’d die. We’d last about four blocks.”

Never averse to a good time, Fountain hit on the idea of forming his own walking club after seeing all the fun had by members of such venerable outfits as the Jefferson City Buzzards. Initially, he, Beverly, and a handful of other couples set offfrom Franky & Johnny’s restaurant in Uptown New Orleans. The wives moved way too quickly for their husbands, who were inclined to make numerous stops for “refreshments.” “We got to Canal Street, and the girls wanted to walk back. We told them there was no way we could walk back, because we were smashed. So we all got a ride back. The next year, we left the girls home, because they outwalked us.”

Pete Fountain in 1968

Beverly suggested the “Half-Fast” name, based on the pace her husband and his friends set, as well as the half-cocked manner in which the idea was conceived and executed. They gradually fine-tuned the operation; the wives formed their own organization, the Better Halves.

By tradition, Fountain and his krewe embark from Commander’s Palace, the flagship old-line New Orleans restaurant, at 7 a.m.. on Fat Tuesday. They make their way to St. Charles Avenue and head downtown ahead of the Zulu parade, to the French Quarter. Along the way, they are fortified by sympathetic establishments. “They used to drink us,” Fountain said in 2001. “Now they feed us. I’ll have maybe a glass of wine mixed with Perrier water to start with. Then during the day, if the beer wagon’s close, I’ll get me a draft.”

Originally, they walked to a pace set by Fountain’s clarinet and a drummer. More recently, a 16-piece ensemble rode in an official bandwagon up front, with eight more musicians in the rear. A truck hauled beads, doubloons and other essentials, replacing the individual carts that members once woozily navigated down crowded streets. They costumed as a group-pirates, gypsies, Indians, Vikings, Romans, Egyptians. Once, Fountain was a prince while the rest were frogs. Another year, he strolled the streets of his hometown in a tutu. All in the name of fun.

In the late ‘90s, actor John Goodman became an honorary Half-Fast member after he showed up at Commander’s Palace one Mardi Gras morning. “He adopted us,” Fountain said. “He gets on the truck, people don’t bother him, and he’s happy up there.”

Fountain started riding, rather than walking, around the same time, as he approached his 70th birthday. In 2001, he resolved to get in shape and get back on the pavement. “I had picked up so much weight that I couldn‘t walk that far. I rode, and I really missed the street. So I’m leaving the band and John Goodman on the truck. He says he’ll hold up my spot, and I’m going to try and walk as far as I can.”

Quitting the Half-Fast club is not an option: “Once you walk, you’re hooked.” Fountain planned to stay on the street “as long as I can toot and scoot. And if I can’t scoot, I can always toot.”

In March 2003, the gold curtain came down on an era of New Orleans nightlife. With little fanfare, in front of 400 mostly invited family and friends, Fountain performed for the last time at his nightclub in the New Orleans Hilton.

For 43 years, New Orleans boasted a club bearing Fountain’s name. He spent the final 26 in the Hilton Riverside, where the likes of Bob Hope, Doc Severinsen and Don Rickles dropped by to lend a hand. For years he punched in five nights a week at the Hilton, but gradually scaled down to two. His graying audience didn’t get out as much any more. Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the overall downturn in tourism eroded attendance further.

He probably could have held on a while longer, but, at 72, Fountain was ready to simplify his life, to rid himself of the pressures and responsibilities of running a nightclub. With his Hilton lease about to expire, he and Benny Harrell, his son-in-law and longtime manager, decided it was time to move on. “I needed a change,” Fountain said. “I didn’t want it, but I needed it. It’s one of those things. The club was still making it, but we could see the handwriting on the wall. It‘s been a real good ride, and we’ve still got a lot of riding to do. I might get off the motorcycle and ride a little scooter now, but it’s still a ride.”

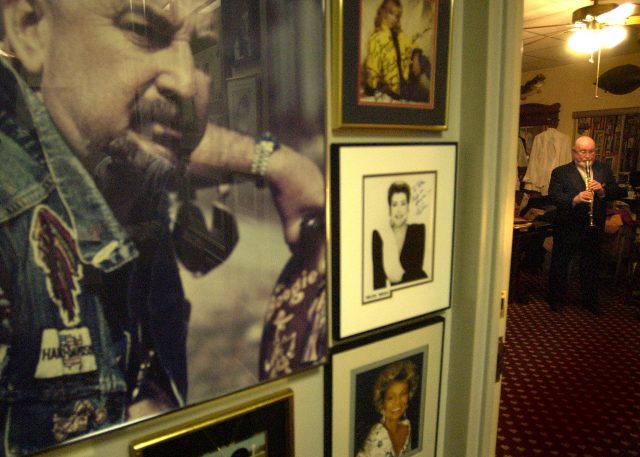

Pete Fountain at his nightclub in the New Orleans Riverside Hilton Hotel in 1988

The club was retiring, not Fountain. He still received more offers for private and corporate engagements than he cared to accept, and had dates penciled in 10 months in advance. He would soon add a twice-a-month gig at a casino near his weekend home in Bay St. Louis.

Still, the final Friday at the club felt like a farewell. The office behind the stage served as the headquarters of his working life for a quarter century. The walls amounted to a de facto hall of fame for a golden era of American entertainment. They bore autographed portraits of Frank Sinatra, Louis Armstrong, Johnny Carson, George Carlin (who, much to Fountain’s amusement, wrote, “Hey Pete: F -you!”) and pictures of Fountain performing for Pope John Paul II and President George H. W. Bush. Beverly Fountain scanned the overcrowded wall and wondered where they would store all the mementos. “We don’t have much wall space,” she said. “It’s nice to have all those memories, but where do you put them?”

As showtime approached, Fountain’s clarinet lay atop his desk as a lamp warmed the instrument’s wood. Five of his six grandchildren — their photos lined the desk — collected quick hugs and kisses from him. His eldest granddaughter, Danielle Harrell, called from New York — where she was auditioning to dance in a Broadway musical — to wish him well.

For the last time, the club’s staff, including Fountain’s two sons, would fret over seating arrangements. For the last time, Dorothy M. Bradley, Fountain’s secretary since 1960, would escort guests to their tables. For the last time, Paul Famiglio, a bartender in Fountain’s employ for 40 years, poured the drinks that made the jazz go down smoother.

And for the last time, Fountain and his six musicians gathered in his office, pulling on tuxedos and loosening up with ribald jokes. They passed through a small locker room and up five steps to the stage. A collage of naughty pictures near the steps was temporarily covered up: The Rev. Frank Coco, the chaplain for the Half-Fast Walking Club and an amateur clarinetist, was scheduled to sit in on closing night.

So, too, was New Orleans coroner/trumpeter Frank Minyard. “He sat in for the opening night,” Fountain quipped. “We want to see if he got any better in 26 years.”

As the clarinetist fidgeted behind the gold lame curtain, the audience laughed and cheered throughout a seven-minute video retrospective of his career: The buttoned-up Welk bidding farewell to the rascal Fountain. Dolly Parton kissing his bald head. President Clinton testifying that the sound of Pete’s clarinet is “one of the joys of American music.”

The curtain peeled back to reveal Fountain center stage, gliding through “Clarinet Marmalade,” still the embodiment of the laissezles-bons-temps-rouler spirit at the heart of Dixieland jazz.

It was a night for old friends and old favorites. The audience sighed its collective approval at the first notes of “Just a Closer Walk With Thee” and “Basin Street Blues,” beloved staples of the Fountain repertoire. Burt Boe and Greg Harrison paired their horns with the master’s for a three-clarinet summit. Minyard navigated “Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans?”

As the 90-minute set drew to a close, Fountain said, “It’s been 26 years here. It went by half-fast, and so did my liver.” He introduced his grandchildren at the final curtain call. “I’d like to thank everybody. I love you, I love you, I love you. See you next time. Thank you very much.”

Minutes later, he had shed his tuxedo and was out amongst friends, exchanging hugs, signing autographs, posing for pictures, accepting congratulations, and looking ahead to the next stage of his ride. “After all these years, it feels strange. But nothing stays the same. It’s time to move on.”

![]()

Generations of well-to-do New Orleanians have flocked to Bay St. Louis to escape the heat, demands and distractions of the city. An easy 45-minute commute separates the two destinations, which are light-years apart in temperament and tone. Bay St. Louis is a quaint, hospitable Southern town with a thriving arts community arrayed along a broad inlet opening into the Gulf of Mexico. From the early 1970s on, Fountain spent weekends he wasn’t working on the Mississippi Gulf Coast.

He built a grand waterfront estate. He moved a two-story house to his property and set it atop a 15-foot-tall first-floor clubhouse. He outfitted the clubhouse with the vintage carved oak bar from Storyville, a New Orleans barroom he owned in the 1960s. On the fully stocked bar’s copper top stood an antique cash register. There were pool tables, vintage pinball and video games, a sauna. Breezes blowing off the water caressed the rocking chairs on a broad, plantation-style porch. Time stood still, stress evaporated; it was the perfect setting for a peaceful retirement. It wasn’t a bad place to conjure and cure a hangover, either.

On Saturday, August 27, 2005, Pete and Beverly drove to Bay St. Louis. They planned to secure the property in advance of the approaching hurricane, then drive back to New Orleans. At least, that’s what Pete told Benny Harrell. “He lied to me,” Harrell said, laughing. “He was going to try to stay there the whole time.” Sure enough, that night Harrell got another call from his father-in-law. He and Beverly wanted to ride out the storm in Bay St. Louis. They figured that the house was solidly built, and even if the ground floor flooded, they’d be fine on the upper two floors. Harrell wasn’t so sure. By Sunday morning, he was increasingly frightened by Katrina’s destructive potential. With the storm slated to make landfall that night, he got on the phone with his in-laws and insisted they flee the coast.

Pete Fountain performed with Al Hirt at the grand opening of the Louisiana Superdome in New Orleans in 1975.

Reluctantly, Fountain agreed. As he paused to set the burglar alarm — in hindsight, an almost comic precaution, given that wind and water would soon steal the entire house — he grabbed a clarinet from the table near the door, where he’d left it after a gig four nights earlier.

With no set destination, he and Beverly drove 24 miles north to Picayune, Miss. Incredibly, they found an available room at a Super 8 motel and hunkered down. The storm crashed ashore just east of New Orleans — better for New Orleans, far worse for Bay St. Louis. The punishing storm surge, ton upon ton of angry Gulf water, roared up out of the bay and bulldozed everything in its path, including the Fountain estate.

Katrina’s winds roughed up Picayune as well, knocking out power and water at the Super 8. For two days, Harrell — who rode out the storm on the western edge of New Orleans in Metairie — did not know where Pete and Beverly were.

Pete’s son Jeff finally reached them. Picking his way around downed trees on back roads, he collected his parents at the darkened motel and drove them to Winnsboro, in central Louisiana.

The Bay St. Louis house, they later learned, was crushed, obliterated. Had the Fountains stayed, in all likelihood they would have perished.

Weeks later, they returned to pick through the rubble. There wasn’t much to find. The game room, Pete’s Porsche, the antique 1930s-era Ford, the 1940s pickup truck, the antique furniture, all the other toys, everything … gone.

His house near Lake Pontchartrain in New Orleans did not flood, but wind damaged the roof, admitting rain, then mold. Power would not be restored for many weeks. His Lake Vista neighborhood was in bad shape, but the adjacent Lakeview, which flooded badly, was far worse. It was no place for a couple in their 70s.

So the Fountains hopscotched across South Louisiana on an odyssey of borrowed and rented dwellings. They stayed for a time in Lafayette, where their first great-granddaughter, Isabella, born two weeks before the storm, was christened. They borrowed a fishing camp in Vacherie from their banker; in return, Fountain appeared in a TV commercial for the bank. They finally settled in Hammond, a college town north of Lake Pontchartrain, for the remainder of their months-long exile.

Even ever-sunny Mr. New Orleans was not impervious to storm-related depression. He lost so much, not the least of which was his way of life and sense of security and home. He had always been healthy, except for booze-induced “flu”; perhaps, his son-in-law theorized, all the drinking over the years killed off other bugs.

But Katrina didn’t claim all victims immediately. The difficult months that followed chipped away at sanity, triggering suicides and overdoses. The stress, strain and upheaval took an especially physical toll on elderly Gulf Coast residents.

Mardi Gras 2006 fell on February 28, six months after Katrina nearly to the day. Fountain generally spends the night before the Half-Fast Walking Club parade at Hotel Monteleone in the French Quarter. On February 27, he was in his room, resting. But something didn’t feel right. He looked terrible by the time Harrell arrived to check on him. At a nearby hospital, doctors discovered blocked arteries. The next day, the Half-Fast Walking Club walked without Fountain for the first time in 45 years, much to his dismay.

He went under the knife for a quadruple bypass days later. Doctors recommended he rest for at least six weeks.

Fountain was still in the hospital when Harrell asked him what he wanted to do about his scheduled gig at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival — which was six weeks away.

This would be the first Jazz Fest after Katrina. It would also be Fountain’s first performance since the storm, and his first following quadruple bypass surgery.

“He basically said, ‘I have to do Jazz Fest. If I don’t do Jazz Fest, I might not play again,’’’ Harrell recalled. “It was a big thing for him. It was a pivotal moment.”

And so, with his cardiologist in attendance just in case, Fountain eased onto the stage of Jazz Fest’s Economy Hall Tent to rapturous applause.

More troubles followed. In the coming months, two strokes, one minor, one more serious, left him with limited speech — but did not hinder his ability to make a clarinet sing. In January 2007, he underwent an operation to relieve lingering pain caused by shingles.

A month later, he returned to the streets, riding in front of the Half-Fast Walking Club. Mr. New Orleans, back where he belonged.

![]()

In the summer of 2009, the Blue Room reopened in the Roosevelt Hotel, the newly restored former Fairmont Hotel on Baronne Street in downtown New Orleans. For decades, the Blue Room was a first-class supper club on the national circuit, hosting all manner of marquee entertainers: Louis Armstrong. Frank Sinatra. Sonny and Cher. Tony Bennett. Ella Fitzgerald. Marlene Dietrich. Jimmy Durante. Bette Midler. It was where real-life “Mad Men” would squire wives and/or mistresses for a classy night on the town. Many a New Orleanian harbors fond memories of special occasions spent there.

The Blue Room closed long before Katrina shuttered the Fairmont. After the storm, the 504-room hotel was acquired by the Hilton Hotel Corporation as part of its Waldorf-Astoria portfolio. The new owners restored the Roosevelt name and refurbished the Blue Room. They wanted opening night to harken back to the Blue Room’s glory years.

Paging Pete Fountain.

Fountain first played the Blue Room in the 1940s, and returned dozens of times over the years. On reopening night, he would be paired with clarinetist Tim Laughlin, his heir apparent. As a young man, Laughlin attended a handful of shows at the old Blue Room, including the Mills Brothers and Mel Torme. But he had never graced the stage until he shared it with Pete, his mentor and close friend. “It was almost spiritual in a way,” Laughlin would say later. “One of the biggest honors I’ve ever had. And to do it with Pete is a notch above that.”

The new Blue Room altered the classic appearance only slightly. Tables are set on two tiers, per tradition. But the low stage on which performers once ventured out among tables has been replaced by a herringbone-patterned dance floor. Musicians now occupy a raised stage set into the room’s back wall.

Pete Fountain warms up before his last show at the club the bears his name at the Hilton Hotel. Courtesy of the Times Picayune, photo by John Mccusker.

Take away the iPhones and opening night could have passed for the Blue Room circa 1963. Water glasses reflected blue stage lights. A massive chandelier sparkled. Elegantly attired guests who paid $195 a ticket dined on lobster and filet mignon. Laughlin and an expanded edition of his band unspooled a program of jazz standards and original compositions. The latter included “For Pete’s Sake,” a song Laughlin wrote in honor of Fountain. Every musician but Fountain wore tuxedos; he opted for a dark suit and tie.

Men in suits and women in cocktail dresses crowded the dance floor. They danced right on through the spiritual “Just a Closer Walk With Thee” (“It’s done in a tempo where you can get away with it,” Laughlin said). Fountain tooted alongside Laughlin, passing the torch even as his own flame continued to burn.

After a final “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue,” fans pressed against the stage to shake Fountain’s hand, collect an autograph on blue souvenir menus, or just be near him. As he made his escape, grinning broadly, speaking little, a man exclaimed, “The whole city loves you.”

Of course it does. He is Mr. New Orleans, continuing on his merry way, as long as he is able.

![]()

Groove Interrupted: Loss, Renewal, and the Music of NewOrleans by Keith Spera (St. Martin’s Press, 2011). is a compilation of stories profiling New Orleans musicians — including Allen Toussaint, Fats Domino, Mystikal, Terence Blanchard, and Jeremy Davenport, among others — in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

Keith Spera, a New Orleans native, is a writer for The Advocate in New Orleans. In addition to his work for the newspaper, he has contributed to Rolling Stone, Vibe, Blender, and LA Weekly.