New Orleans as a Nexus of Power

American Empire, Bananas, and the Crescent City

Published: June 1, 2024

Last Updated: September 1, 2024

Photo by Carl Mydans, United States Resettlement Office, Library of Congress

Marketplace in New Orleans, 1936.

The business of empire building is often political and public. In the case of US expansion into Latin America and the Caribbean, it was largely tied to small businesses run by families that later became corporations. Several of these families were based in New Orleans, and everyday citizens actively participated in the process. But despite the long and well-established historical ties between Louisiana, the Caribbean, and Latin America, scholarly examinations of the political, economic, cultural, and military expansion of the United States into these territories in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century rarely include New Orleans as a focal point of discussion. Evidence of the city’s impact on these regions’ economic and political landscapes is most often found in private family collections and lore, including my own.

While studying for a PhD in history in the early 2000s, I initially struggled to find a research topic for my dissertation. I was committed to a focus on the Caribbean and Latin America but unsure of how to narrow the scope of my scholarship. On a visit home to Houston one summer, I had a conversation with my grandfather about my dilemma. He responded nonchalantly, “You know, my N’oncle Gus left Rosa [Louisiana], got on a boat in New Orleans, and ended up in Honduras, where he made a lot of money. He ended up living in a big house on Lake Pontchartrain. He used to bring us bananas and all other types of strange fruit when he would visit. Why don’t you write about that?”

My entire life I heard my grandparents tell stories of siblings and cousins who left Louisiana and went to California, Chicago, Detroit, and other points North and West during the Great Migration. No one ever mentioned family leaving the United States. Also, how does a Black man from rural South Louisiana at the turn of the twentieth century even find out about such an opportunity, much less return to Louisiana substantially enriched and live in an exclusively white community before the Civil Rights era? Needless to say, I was intrigued by my grandfather’s story.

When I returned to school in Washington, DC, I visited the Library of Congress and the US National Archives with nothing more than my grandfather’s uncle’s name, some dates to estimate his age, and his home parish. On my first day of research, I came across US State Department records from 1906 that listed the names of Americans living abroad in La Ceiba, Honduras. One of the first names I saw on the page was August Monteilh. N’oncle Gus! In addition to August Monteilh, there were 177 other men, Black and white, claiming US citizenship. Most were from Louisiana or neighboring Gulf Coast states, and all were working in the tropical fruit industry.

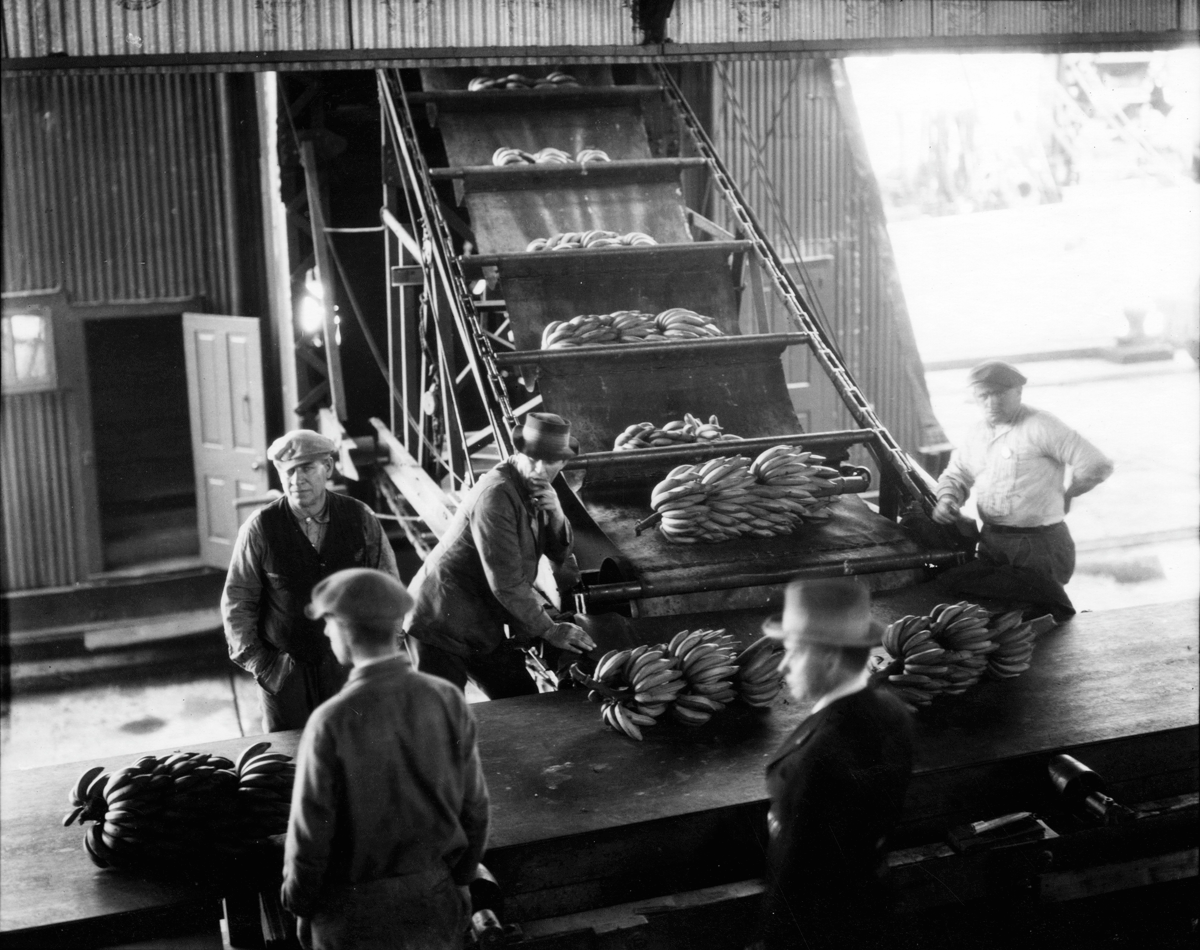

Workers unload bananas from a conveyor belt. Charles L. Franck Studio Collection, The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Between 1898 and 1935, the United States launched dozens of military interventions into Latin America and the Caribbean. The justification for use of military force was almost always to protect US economic interests; the banana industry and its shipping routes were the primary recipients of US military protection. By the early 1910s, bananas had gained popularity among the American public after an aggressive marketing push by US–based fruit companies promoting the fruit’s nutritional value, with advertisements featuring celebrities, doctors, politicians, and various other public figures helping create demand for the fruit. The infrastructure subsequently created by the banana industry—which included railroads, shipping, marketing, and advertising—also allowed for the inflow and outflow of additional commerce, creating thousands of jobs throughout the major port cities of the United States.

La Ceiba and other cities along the North Coast of Honduras, such as Trujillo, Tela, Omoa, and Puerto Cortés, had functioned as commercial trading ports during the Spanish colonial period and continued as such following Honduran independence. Permanent settlement was small, consisting primarily of mixed-race peoples of Indigenous, African, and European descent, until the development of large-scale banana production that brought a massive influx of foreigners and capital. Louisiana men were thus at the forefront of the burgeoning US presence in the region.

August Monteilh worked in a supervisor role for the Reynolds Company, which cultivated sugar and operated a distillery in the vicinity of La Ceiba. The position allowed him to utilize a skillset he’d honed on his family farm in St. Landry Parish. By 1935 there were over 1,500 men, mostly from Louisiana, working in the banana industry in Honduras. In finding N’oncle Gus, I also found out his secret. He was able to gain success in part by taking advantage of the racial fluidity in Honduras. As a mixed-race Creole, N’oncle Gus departed Louisiana a “Negro” and returned years later as “white.” Grandpa left out that part of the story.

It is not an exaggeration to say that the banana industry may not have existed without New Orleans. The city, due to location and historical ties, was the main port through which bananas were first distributed in the United States and served as the site for home offices of all the major fruit companies in Honduras at one time or another. In 1897 Albert Morlan, an independent traveler from Indiana to Honduras, noted in his diary that many of the local Honduran fruit developers fought tirelessly, and unscrupulously, to monopolize control over the Honduran banana industry and maintain their contracts with New Orleans– and New York–based importers. The stakes were high; the Honduran government at the time was seeking to modernize the nation and felt that agriculture offered the best conduit for economic development. Initially, coffee was the chosen crop in Honduras. However, lack of infrastructure to transport the crop from the mountainous interior to the coast, along with a series of military coups d’état and a lack of international investment, made it impossible for Honduras to compete with other coffee markets. The Honduran government decided to shift focus to bananas, which had already garnered some foreign investment.

US State Department records from 1891 estimate that some ten to twelve American steamships called at the Port of La Ceiba every month from New Orleans and New York. These merchants connected Honduras to an emerging North American market for “exotic” tropical fruits such as bananas, pineapples, and citrus. La Ceiba thus became the center of a large district devoted to the production of tropical fruits for export to the United States. Meanwhile the large ports of the northeastern and southern United States, combined with the US transcontinental railroad system, enabled sale of the fruit throughout the country.

Samuel Zemurray and his Cuyamel Fruit Company (later acquired by United Fruit Company, now Chiquita) were the first to take advantage of this new market on a large scale, establishing the blueprint for how US capital could influence—and control—the economic and political landscape of Central America. Zemurray, a Russian Jewish immigrant from Bessarabia (now Moldova), began his banana merchant career in Mobile, Alabama, buying surplus bananas in railroad cart loads and selling them to local dealers. In 1905 he moved to New Orleans and contracted himself out to the United Fruit Company to sell bananas that had ripened aboard ship and needed to be disposed of quickly. In 1910 Zemurray and his partner Ashbell Hubbard purchased five thousand acres of plantation land in Honduras near the Cuyamel River, in the vicinity of Omoa. Their Cuyamel Fruit Company, headquartered in New Orleans, built railroads in Omoa to transport its product to sea-faring vessels; constructed canals to maximize agricultural development on its lands; developed a company town; and built shops, similar to a military PX, selling US consumer goods.

Zemurray was further able to expand his company by building alliances with future Honduran president Manuel Bonilla and financing his efforts. For much of the early twentieth century, Honduras was plagued by military conspiracies and civil wars resulting from elite aspirations for political power, conflicts over disputed elections, and presidential succession. Fruit companies became good at anticipating these conflicts (and the eventual winners). As a payout for supporting Bonilla, Zemurray received large tracts of additional lands, and the Honduran government waived his tax obligations.

Over time the Cuyamel Fruit Company came under strong criticism in the Honduran press for what was seen as its strain on the local economy. While the fruit companies and Honduran politicians became extremely wealthy from the banana industry, very little of that wealth trickled down to the rest of population, and areas outside of the fruit company zones were not developed. Because the fruit companies were foreign enterprises owned by Americans, the wealth generated from bananas was sent back to the United States and invested there. Most Hondurans continued to live in poverty.

The story of Standard Fruit Company (now Dole) is very similar to that of Cuyamel. Brothers Joseph (Giuseppe), Luca, and Felix Vaccaro and their associate Salvador D’Antoni were Sicilian immigrants based in New Orleans who began importing bananas from Honduras to New Orleans as early as 1899. By 1905 the Honduran government awarded the Vaccaro Brothers a concession to export fruit from La Ceiba in exchange for a promise to build canals in the region. Their company also built jetties, docks, and other structures necessary for the development of their business; contracted with smaller local companies; and acquired access to additional canals and ports. To encourage their business endeavors, the Honduran government exempted the company from customs duties on imports and exports. Incorporated in 1924 as Standard Fruit Company, the Vaccaros’ business became the main economic engine in La Ceiba; borrowing extensively from the model established by Zemurray, Standard Fruit bought and wielded significant political and economic influence. They also employed hundreds of workers in various subsidiary businesses throughout New Orleans tied to the fruit and shipping industries.

The fruit companies gained enormous profits; by aligning themselves with the fruit companies, Central American oligarchs grew extremely wealthy. The methods employed by these companies established Honduras as the quintessential “banana republic”—in other words, a nation that functions as a private commercial enterprise for the exclusive profit of the ruling class, willing to sacrifice their nation’s economic and political sovereignty for foreign capital.

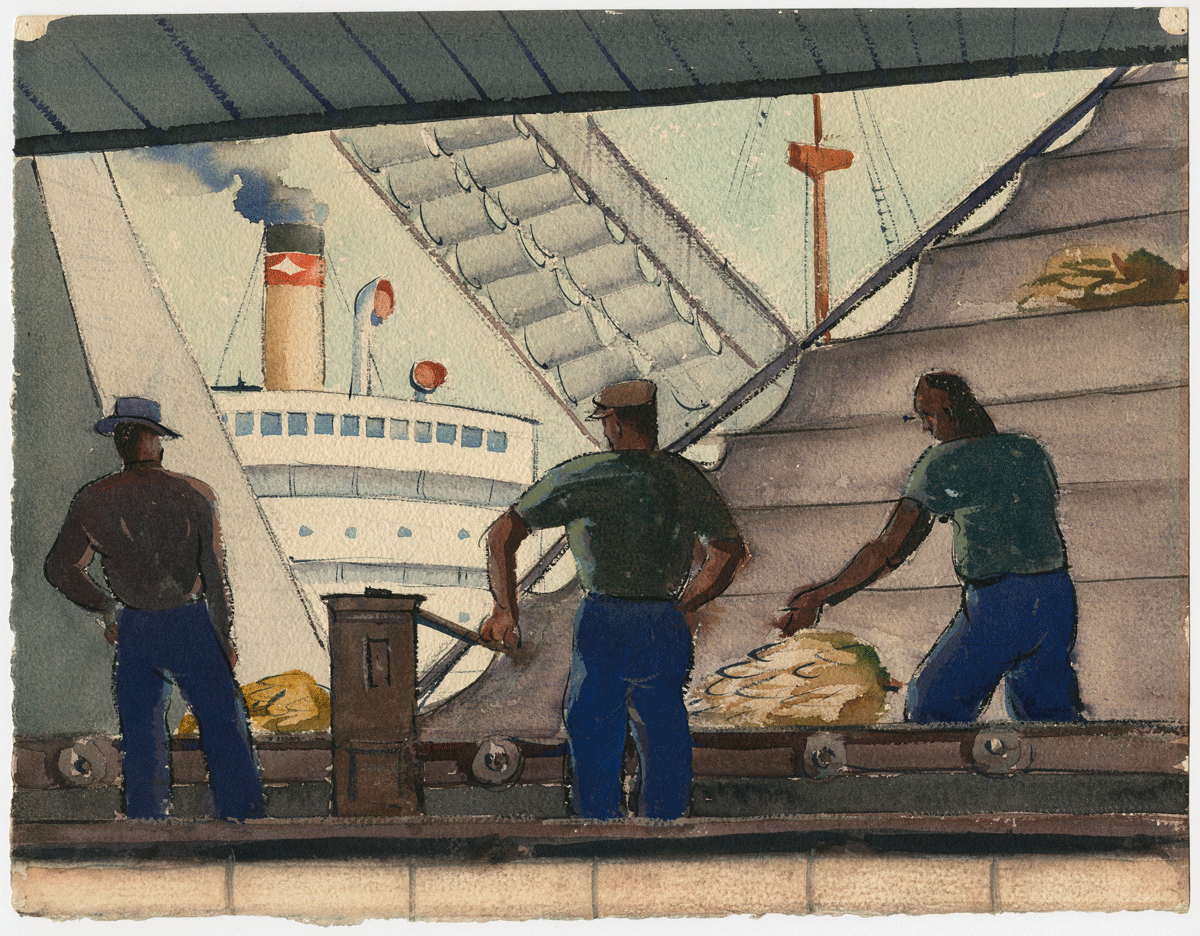

Paul Starrett Sample, Dock Workers Unloading Banana Boats, ca. 1935. Watercolor and tempera. The Historic New Orleans Collection.

On numerous occasions while traveling in Honduras during the early 2000s conducting research in the banana zones of the North Coast, I heard Nueva Orleáns as the one US city that older Hondurans recalled with nostalgia. Though many of these Hondurans had never visited the city, ships from New Orleans arrived frequently to the ports. These ships brought commercial goods, access to news from the larger world, and, by the 1930s, employment opportunities for Honduran dockworkers and merchant seamen. The merchant seamen eventually had the opportunity to travel to and from New Orleans quite frequently. While New Orleans–based fruit companies and “banana men” helped to create an economic system that extracted significant wealth from Honduras, the relationship between the city and the Honduran North Coast also provided a sense of possibility to many locals who believed that, if afforded the opportunity to leave the banana zones, they would find their best chance of success in New Orleans.

The international clout wielded by the fruit companies coincided with US government desires to expand its political reach and economic power. This expansion, unlike its European predecessors, would not be based on the acquisition of large territories and the establishment of hegemonic political rule through force. There would be no “US subjects” or “citizens of the American Empire” analogous to the British or French. The United States exerted economic influence through what was termed “soft imperialism,” without creating national ties. The playbooks for this expansion were legislated by politicians in Washington, DC, and enforced by the US military. But the first architects of this endeavor—and the initial capital and labor—came from New Orleans.

Glenn Chambers is a professor of history and interim dean of the Residential College in the Arts and Humanities at Michigan State University. He specializes in Central American and Caribbean history, particularly the economic expansion of the United States into the region and its impact on labor, race, and migration patterns. A native Houstonian with strong cultural and familial ties to South Louisiana, his work draws on the historical connections between the Gulf Coast and the Caribbean.