New Orleans Prisons

A geographic exploration

Published: March 1, 2020

Last Updated: June 1, 2020

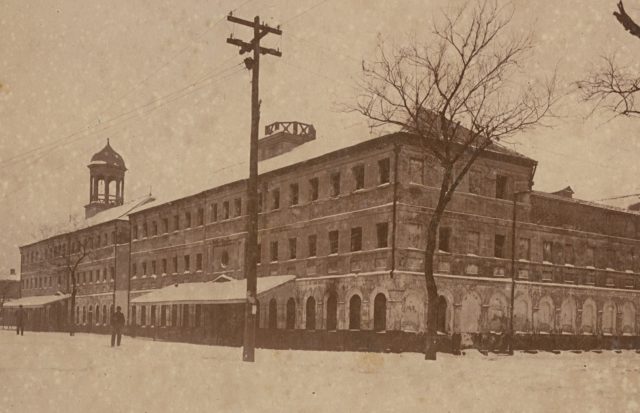

Photo by the Detroit Publishing Company, Library of Congress

Detail of criminal court and prison complex viewed from Elks Place, ca. 1906.

It didn’t start off this way, of course; the incipient city had so small a footprint that lawbreakers had to be kept close to lawmakers, indeed practically within their very walls. For the first hundred years, a series of calabooses operated in various forms behind the French corps de garde and the Spanish Cabildo, where anyone from pickpockets to murderers, from captured runaways to prisoners of war, were imprisoned. The extant Cabildo, completed in 1799, still retains jail cells in its rear dependencies, their massive wooden doors and iron hardware making clear their design purpose.

There was another type of “prison” in colonial New Orleans, not for lawbreakers but for the law’s victims. Prison-like pens or compounds for enslaved Africans operated on the Company (later King’s) Plantation, a space selected because it was close enough for surveillance and convenience, yet far enough—across the river from New Orleans—for the purported safety of the enslavers. Located behind where the Algiers Courthouse now stands, this “camp for the negroes,” according to its architect Le Page du Pratz, comprised “a square in the center, and of three wide streets where I laid out their cabins, between which I left an adequate space [for] strong palisades.” The thirty-two cabins with vertical–timber walls held a revolving cohort of up to 154 people.

The slave pens of a century later, which served as provisional spaces for victims of the domestic slave trade, were comparably located just outside the original city (French Quarter), as ordinances required them to be located in less-dense adjacent faubourgs, namely Marigny and St. Mary, again purportedly for reasons of public health and safety.

As for those accused or convicted of crimes, their prison geography was also shifting. By the 1820s, population density made a prison in the heart of the French Quarter impractical, so a new facility was established seven blocks back toward the swamp, on Orleans Street in the Faubourg Tremé. The Cabildo’s calaboose, meanwhile, was demolished and replaced by the Arsenal, although a police station and jail cells operated on site into the early 1900s, and may be seen in the courtyard’s upper galleries today.

The new Orleans Parish Prison in Tremé, designed by architects Joseph Pilié and A. Voilquin and erected during 1831–1836, had an austere Franco-Spanish visage, with stuccoed walls and long arcades, interior courtyards with galleries, and separate cell blocks depending on offences. Two cupolas rose from the hipped roof, and sycamore trees lined the compound walls.

By century’s end, the Tremé prison, its aura by now perfectly Dickensian, proved inadequate for modern needs. Populations had since expanded predominantly upriver, and most government offices had moved above Canal Street as well. Authorities contemplated something new: a centralized, co–located complex for judicial, constabulary, and punitive functions. In February 1892, the city issued a call for architectural proposals.

Detail of Orleans Parish Prison, located between Marais and Tremé Streets, in the snow, 1895. Photo by Ernest J. Bellocq. The Historic New Orleans Collection

The new location would be in the rear of the First District, today’s Central Business District, on the square bounded by Gravier, Common (now Tulane Avenue), Basin (South Saratoga, now Loyola Avenue), and Franklin (now gone). This was the area that Louis Armstrong, who spent his childhood years nearby, described as the “back-a-town”; others called it “the Battleground” for its violence. Chinatown and its rumored opium dens sat across the street, and the decades-old vice district that would later become Storyville (1898) lay only two blocks downriver. A display of official power here, authorities surmised, would bring order to this notorious realm.

What the city sought was a $350,000 multi-use complex to include a parish prison to incarcerate three hundred men and fifty women, plus cells for the condemned, a chapel, and a mortuary; a criminal courthouse with trial rooms and chambers for judges, attorneys, clerks, and juries; a recorder’s office; a citywide police department headquarters; and a local precinct police station. This new concept, of spatially agglomerated constabulary, judicial, and penal operations, would become a permanent feature of New Orleans government.

The winner of the competition was the Dallas-based architect Max A. Orlopp Jr., whose design would stun the eye and cower the crook: a castle-like edifice with “circular towers rising in the center,” wrote a Picayune reporter wryly, “castellated, with turrets, battlements and slits for the archers[;] a sort of hybrid architecture, with a mixing of the Romanesque [and] the Gothic.” A reconnoitering clock tower rose high above, the nineteenth-century equivalent of today’s police cameras. The Criminal Courts Building and adjacent Orleans Parish Prison all shared the same daunting guise, such that the entire complex, salmon-red in color, looked like one colossal citadel.

Appearances aside, Orlopp’s courthouse had serious structural flaws, and coupled with revelations of corruption in the bidding, the whole pile of bricks gained a bad rap. Worse, the facility swiftly became obsolete, as new technologies in calefaction and illumination came to architecture, and automobiles and radio communications came to policing. Architectural tastes changed in the 1910s and 1920s, after which the complex came across as flat-out medieval–looking. Folks started called it the “Old” Criminal Courts Building, despite that it was all of a couple of decades old.

Then there was geography. The new City Planning Commission felt this downtown location, ripe for renewal, suffered from the prison stigma, and that such a land use ought to be “pushed back.” In 1931, prison and court functions were relocated to new facilities at Tulane and Broad, over one mile straight back on Tulane Avenue, into the former backswamp, which by now was entirely drained and largely urbanized.

Further deterioration necessitated the removal of the Old Criminal Courts Building’s landmark tower in 1940, and the rest of the complex followed in 1949–1950. Over the next decade, the entire “back-a-town” of Louis Armstrong’s youth would be expropriated, demolished, and redeveloped as today’s civic center, including city hall, Duncan Plaza, and the public library.

In time, the circa-1931 Orleans Parish Prison on 531 South Broad would also become antiquated, and the City Planning Commission in the 1960s called for a modern replacement nearby at Gravier at South White. That prison, opened in the late 1970s, soon earned a reputation as among the worst in the nation, and was itself replaced in the 2010s amid a growing nationwide debate on incarceration—in a place that, until recently, qualified as the world’s most incarcerated city—and state, and nation.

Today, the Orleans Parish Prison, the Criminal District Court, the New Orleans Municipal Court, and the offices of the New Orleans Police Department and Criminal Sheriff are all co-located within two blocks of Tulane and Broad. In a strange serendipity, they are all within a few hundred feet of Louis Armstrong’s birthplace.

The backward spatial progression of prisons reflects New Orleans’s age-old tendency to push unwanted land uses away from the empowered front of the city. It also reflects the changing urban geography of the metropolis as it expanded into former swamplands toward the lake. The current location of the judicial complex is now roughly in the geographical center of the East Bank population distribution, and just about everyone refers to it not by its various institutions, but by its geography: “Tulane and Broad.”

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Cityscapes of New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, Bourbon Street: A History, and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on Twitter.