Fall 2021

Oh, Casanova

How a Cleveland R&B song became a New Orleans brass band staple

Published: August 31, 2021

Last Updated: June 9, 2023

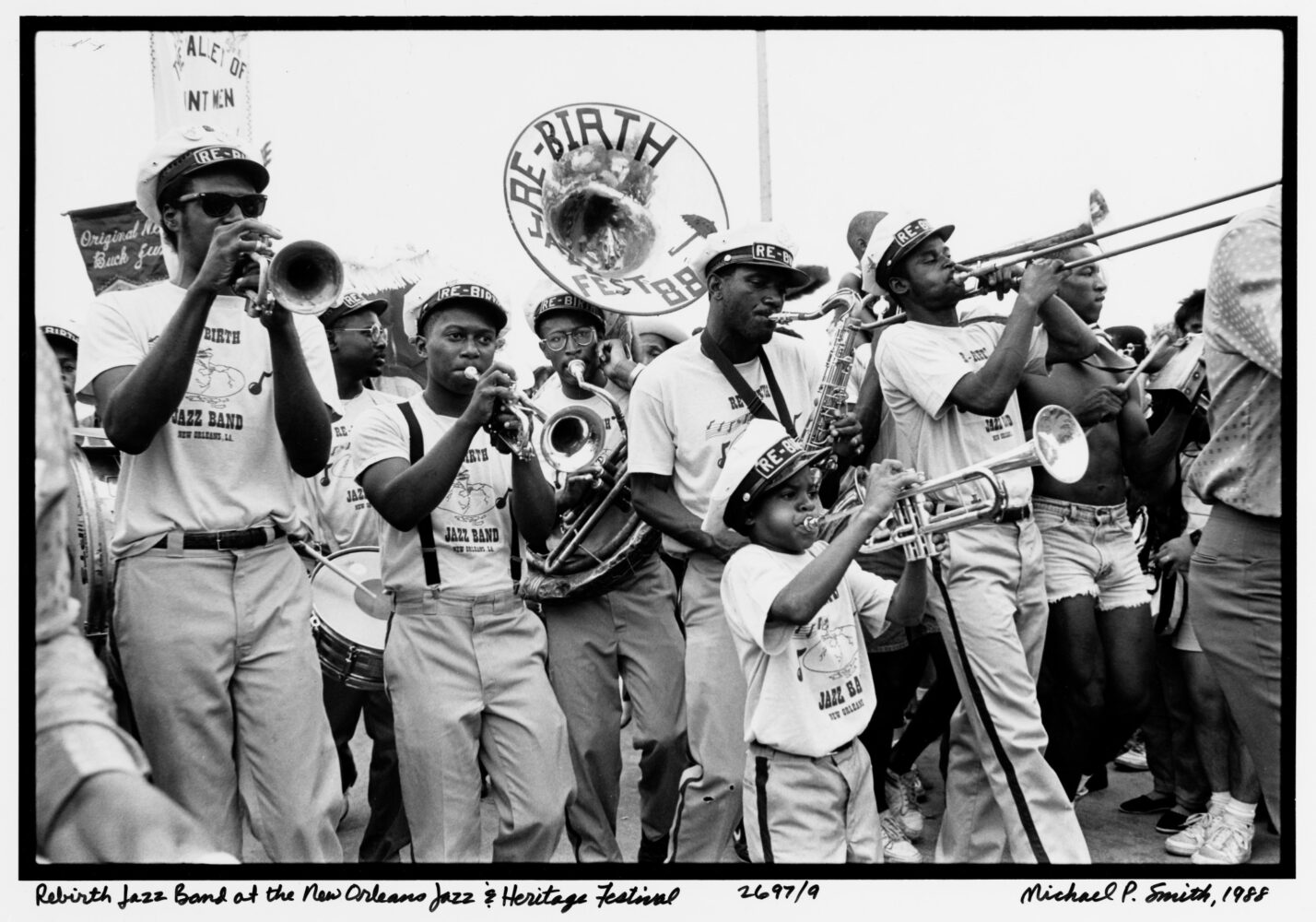

Photo by Michael P. Smith, The Historic New Orleans Collection

The Rebirth Brass Band at the 1988 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival.

“I ain’t much on Casanova

Me and Romeo ain’t never been friends

Can’t you see how much I really love ya

Gonna sing it to ya time and time again…

Oh, Casanova…”

I was barely eight years old when I first heard “Casanova” on Cleveland Black radio. I didn’t know the term “Casanova” was used to describe an uncommitted man involved with many women. I didn’t understand what was meant by the lyrics “me and Romeo ain’t never been friends.” I knew “Casanova” as the song of my neighborhood; the song performed at one of my elementary school talent shows; the song whose familiar beat seemed to always be blasting from cars passing by; the song playing on the jukebox in the Pizza Hut in East Cleveland while my family waited for a large pepperoni.The group LeVert had scored a previous number-one R&B hit with 1986’s “(Pop, Pop, Pop) Goes My Mind,” but they’d never had (and never would again) a hit like 1987’s “Casanova.” Not only was it another number-one R&B hit, but it also made a splash on the US dance chart, reached number five on the pop chart, peaked at number eleven on the Canadian chart, and was a top-ten hit in the United Kingdom.

“Casanova” was inescapable. The song hooked listeners with its simplicity, irresistible beat, and churchy vocals. I had no clue as a little girl that marching bands at historically Black colleges and universities had added it to their repertoire, or that folks in other countries such as Canada were turning up the volume when it came on. The Levert family was musical royalty in Cleveland, similar to what the Neville family is to New Orleans. Eddie Levert is the legendary lead singer of the O’Jays, and the group LeVert included his two sons, Gerald Levert and Sean Levert, and their high-school friend Marc Gordon. The members of LeVert lived in Cleveland, and I thought the popularity of “Casanova” was mostly a Cleveland thing—until I moved to New Orleans.

I first heard a brass band playing “Casanova” after moving to the city in 2006. In my mind, the song transported me back to basement parties in Cleveland, but I was still keenly present in New Orleans culture. A few months later, at a wedding reception in New Orleans, a different brass band played the song. Later that year at a nonprofit gala, yet another brass band played “Casanova.” I’m certain I heard it lots of other times in the next few years, but one of the moments that stands out is Martin Luther King Day 2015, at the abandoned apartment complex in Algiers that the artist Brandan “BMike” Odums transformed into a giant art exhibit. It was there that Trombone Shorty led a brass band playing “Casanova” to a sea of dancing people around me.

There was a brass band at a December 2019 fundraiser we attended in New Orleans, and when my mother, who migrated from Arkansas to Cleveland, heard the band launch into its next number, she turned to me and said, “I know they’re not playing ‘Casanova!’” She knew the song, but she had never heard it like that.

According to an interview published to YouTube site SongVest, when Midnight Star’s Reggie Calloway wrote “Casanova,” he imagined it being sung by a country singer. But Calloway shelved the song for a while and continued building his musical career, until one day a friend convinced a skeptical Calloway to come with him to visit a palm reader. The palm reader looked into the songwriter’s hand and told him a song he had abandoned would be a hit. Calloway thought of the song he’d imagined for a country musician and began perfecting it.

As fate would have it, Calloway was asked to produce LeVert’s third album, The Big Throwdown, for Atlantic Records. The songwriter knew he needed a song with catchy lyrics that would capture the late-eighties R&B sound that would later be called “New Jack Swing.”

Oh! Casanova!

Some of Ohio’s veteran funk musicians backed the track. Calloway and LeVert felt it important to utilize homegrown talent. Cleveland’s own Arsenio Hall invited the group to perform on his popular show in 1987. “Casanova” earned LeVert a Grammy nomination for Best R&B Performance by a Duo or Group. The group lost out to “I Knew You Were Waiting (for Me)” by Aretha Franklin and George Michael.

When a New Orleans brass band plays “Casanova” they are not randomly picking an R&B oldie. The brass band is playing a song that the crowd at the party or second line would expect to hear. It’s playing a brass band staple. In trying to explain its popularity to a friend in Ohio, I say that people in Cleveland listen to LeVert’s “Casanova” at their backyard cookouts. New Orleanians play “Casanova” live in the streets.

From jazz to blues to early R& B, Black popular music and Black soul musicians have often migrated from the south to the north. But the reverse is true for Casanova. It’s a song that migrated south. More than that, it sounds like a song that simply came back home. “It’s like the song was made for the second line beat, ya know?” drummer Keith Frazier, one of the founding members of Rebirth Brass Band, told me.

To Frazier’s point, the first thirty seconds of LeVert’s “Casanova” is a perfect fit to the Bamboula beat heard in Congo Square, where the foundation for second-line music was laid. But no matter which version one hears, there is an inherited African rhythm at the core. “It’s like the funkiest parade polyrhythmic pulse, the bass line of ‘Casanova’ has that habanera/son clave feel that lives in between a shuffle and swing,” said Janice Lowe, a Cleveland poet and music composer.

It’s widely believed that Rebirth is responsible for making “Casanova” a song that every New Orleans brass band had to learn. The song was already a popular R&B hit and in heavy rotation on radio stations such as WYLD in New Orleans. But Keith Frazier said his brother Philip Frazier had them start practicing the song after hearing Southern University’s “Human Jukebox” and Grambling State’s Tiger Marching Band play it. Sometime in the mid-1990s, at the band’s regular Thursday set at Kemp’s Lounge at 2720 LaSalle Street, the band played “Casanova” for the first time, Keith Frazier said, and the tightly packed Kemp’s crowd went crazy. Rebirth transformed the song by having the horns play the notes that had been sung by Gerald Levert. The bassline in the LeVert version is played by the tuba in the Rebirth rendition.

One can hear Rebirth play it on 2004’s Ultimate Rebirth Brass Band album. Rebirth occasionally pauses to sing the “Casanova” hook but they make the lyrics raunchy. “Oh, Casanova,” as sung by Gerald Levert, becomes “Girl, bend over”—because, Keith Frazier said, a beautiful woman in the audience caught the eye of trombonist Reginald Stewart. Keith Frazer said the band didn’t mean any disrespect to women: “it’s just how we party in New Orleans.”

“New Orleans had good food and fiiiiiiine women,” LeVert’s former music director Michael Ferguson told me in a February interview. “When we knew we were going to New Orleans, we tried to build in a day before or after to enjoy the city. I remember us playing the Saenger in the ’90s, and it was a big deal. It was a fun audience.” R&B groups, he said, coveted booking the Saenger because the Frankie Beverly and Maze album Live in New Orleans gave artists such a great impression of a New Orleans audience. According to Keith Frazier, Rebirth opened for LeVert in the nineties but never had an opportunity to have a musical exchange on stage because the brass band was scheduled for another gig in the city.

“It’s amazing to know our song lives on in New Orleans—a city I love,” Marc Gordon, the only surviving member of LeVert, said via email. “In our concerts, ‘Casanova’ was always the closer, the last song of the show and towards the end, we’d break it down, like a Caribbean feel, ironically with a similar groove to what the New Orleans bands play now, and we’d party until leaving the stage.” Gerald Levert died at age forty on November 10, 2006, of what was initially believed to be a heart attack. Autopsy reports showed it was a blend of prescription and over-the-counter drugs that caused his death. His brother Sean died while in the custody of Cleveland police on March 30, 2008. For Gordon and the musicians who backed the singing trio, New Orleans’s embrace of the song serves as an ongoing tribute to Gerald and Sean.

Thirty-four years after its release as an R&B hit, brass bands continue to play “Casanova” in the streets of New Orleans. My daughter, who’s the same age I was when “Casanova” came out, has been singing along to it since she started walking. She was born in New Orleans and prefers the New Orleans version. It’s even crept outside New Orleans. In Acadiana, there’s a popular zydeco version by Keith Frank. LeVert’s former music director Michael Ferguson mentioned hearing a reggae band play it in Jamaica.

Unlike my eight-year-old self, I know now that “Casanova” has been all around the world, and that it has touched many generations along the way. Still, whenever I hear it, I not only think of my original home of Cleveland, but also my adopted home, New Orleans, and the new memories made in streets filled with joy.

Kelly Harris is a poet and the author of Freedom Knows My Name. Read and listen to more of her work at kellyhd.com.