Old Mobile

Archaeological treasures in Louisiana’s first capital

Published: August 30, 2022

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

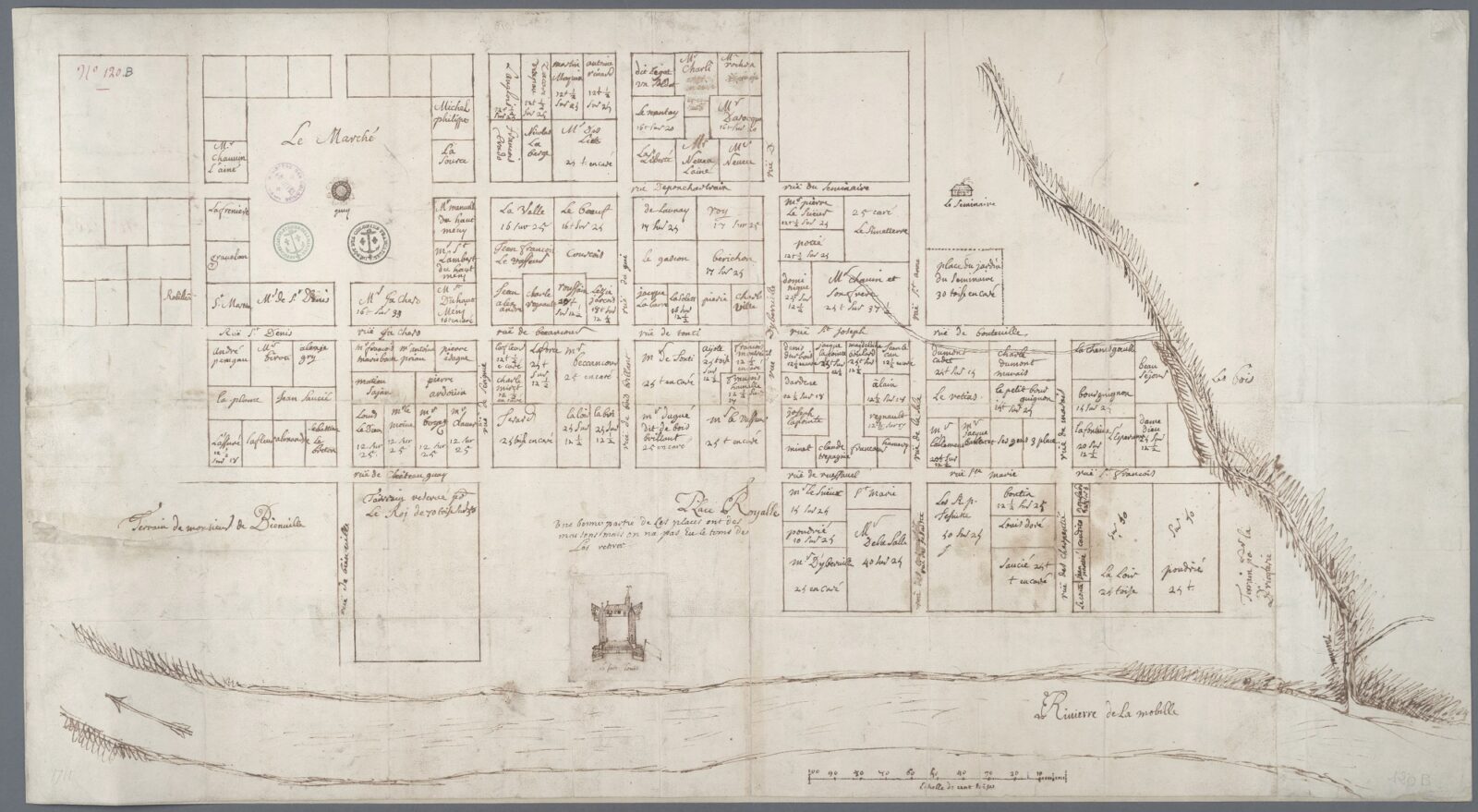

Archives nationales d’outre-mer

Ca. 1704 map of Old Mobile and Fort Louis.

Old Mobile. For most modern-day residents of Mobile, Alabama, that phrase alludes to the city’s wealthiest families, whose scions have reigned over the city’s Mardi Gras mystic societies for generations. For historians and archaeologists looking deeper into the Gulf Coast’s past, Old Mobile means Vieux Mobile, the place north of the modern city where Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville established the first capital of French colonial Louisiane in January 1702.

Between 1698 and 1702, Iberville led three expeditions to claim and colonize the northern Gulf of Mexico’s coast for France, culminating in Mobile’s founding. In the 1680s, Sieur de La Salle had failed spectacularly in a similar effort that ended with the deaths of hundreds of colonists on the Texas coast. For this new attempt, Louis XIV and his ministers strategically put in charge a Canadian with New World experience and considerable organizational ability, demonstrated in Iberville’s brilliant military campaigns against English outposts on Hudson Bay and Newfoundland. The new colony’s survival, however, would depend equally on the diplomatic skills of Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, Iberville’s younger brother whom he left in command at Mobile.

Bienville had scouted the location of the future town in 1700. From their temporary base at Fort Maurepas (present-day Ocean Springs, Mississippi), the French methodically searched the region for a townsite that met several preferred conditions. Firstly, the colonists needed a harbor for their deep-draft ocean-going ships, not an easy thing to come by in the shallow waters of the northern Gulf Coast. A Spanish colonizing expedition had claimed Pensacola Bay, the region’s finest natural harbor, just weeks before the arrival of Iberville’s first fleet. The French did find a small, though adequate, harbor at Dauphin Island, but that sandy, low-lying landform offered poor prospects for a permanent town.

Clay pipe fragments, organized and stored at the University of South Alabama. Photo by Brian Pavlich.

Secondly, the French sought access to the North American interior via a major river, by which they intended to exploit the midcontinent’s furs and (less realistically) precious metals. Bienville searched the lower reaches of the Mississippi River but failed to grasp the settlement potential of a portage location where New Orleans would one day stand. Instead, French attention focused on the Alabama River system that also reached far inland, all the way to the southern Appalachian Mountains. At the lower end of this lengthy river system, along the banks of the Mobile River, they met Indigenous farmers with whom the colonists could trade for agricultural surpluses, their third criterion for settlement.

By 1702 the dwindling population of Mobilians, the region’s Indigenous occupants, ravaged by diseases introduced to the Americas by colonizing Europeans, still occupied several towns bordering the Mobile–Tensaw delta. Since at least 1200 CE, Native American women had cultivated maize and other domestic crops in the expansive bottomlands of that enormous, forested wetland north of Mobile Bay. Spring floods deposited nutrients annually on their low-lying fields, resulting in dependably abundant harvests. When Bienville met with Mobilian leaders, he found them eager to trade, as well as receptive to a military alliance. The Mobilians and the rest of the petites nations, numerous small towns of diverse Native peoples living near the coast, hoped the French presence would finally put an end to raids by Muskogee (Creek) warriors from the north who had been selling captives from other Indigenous groups in the slave markets of English Charleston, South Carolina.

As a place suitable for the colonists’ own settlement, the Mobilians suggested a riverside bluff located a few miles south of their largest town. Known today as Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff for its distance upriver from the head of Mobile Bay, the site of French Mobile met the colonists’ criteria except for proximity to a deep-water harbor. The colonists would have to row or paddle the sixty-some miles to and from their anchorage at Dauphin Island to resupply their settlement.

Pieces of a painted barber’s bowl. Photo by Brian Pavlich.

For this new colonial town, the Le Moyne brothers adopted the name of their newfound allies’ nearby village. However, “mobile” is also, of course, a French (and English) word meaning movable, unsteady, or changeable—troubling connotations that concerned the king’s colonial minister, Jérôme Phélypeaux, comte de Pontchartrain. When Phélypeaux expressed his displeasure with the name Mobile, for its suggestion of impermanence for a colonial capital, Bienville responded, perhaps with tongue in cheek, that the place could instead be called “Immobile.” King Louis ultimately decided, presumably to Bienville’s relief, that Mobile would remain Mobile.

The colonists immediately set to work laying out a street grid centered on their fort, the first formal European-style town plan on the Gulf Coast. Most of the town’s blocks were subdivided into private lots for the settlers, with others allocated for the mission priest and a brickyard. Inside Fort Louis de la Louisiane, overlooking the Mobile River, stood the community’s church, guardhouse, storehouse, and Bienville’s quarters. Taking advantage of a dry spell, the town’s roughly three hundred residents quickly cleared the forest and constructed eighty buildings on a seventy-acre tract.

Then the spring rains came. Apart from Fort Louis and nearby residences on the high bluff, low-lying portions of the townsite reverted to the swampland they had always been. The Mobilian headmen who recommended the bluff to Bienville did not anticipate the French town’s expansive design, far more spacious than their own compact villages. This tendency for low-lying parts of town to flood continued to vex the colonists throughout their time at Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff. Father Henri Roulleaux de La Vente, the seminary priest, complained bitterly during his time at Mobile about the ankle-deep stagnant water that often made his house unlivable. Protests from other colonists similarly unfortunate in their choice of town lot finally persuaded Bienville in 1711 to abandon the flood-prone spot and relocate Mobile to the head of the bay (the city’s modern location), half the distance to their port on Dauphin Island.

The forest regrew, eventually covering the old townsite. In the 1790s, Louise Fièvre, a wealthy widow and daughter of a female deportee from the Paris prisons, acquired the tract that formerly contained Fort Louis and grazed her cattle there. Around 1900, workers at a temporary logging camp, complete with a narrow-gauge rail spur, stripped the marketable timber from the townsite. In the 1950s, several industries acquired Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff and built access roads and pipelines to the river. Through all these intrusions, each of which left its mark on the colonial townsite, the archaeological footprint of Old Mobile remained essentially intact.

Serendipity plays an oversize role in the lives of archaeologists. I arrived in Mobile in the fall of 1988, newly hired by the University of South Alabama and eager to begin long-term research on the poorly known ancient shell mounds of Alabama’s Gulf Coast. Before I could hit my stride with that project, midway through my first year of teaching, I had a call from Jay Higginbotham, author of the definitive history of Old Mobile. Jay told me, with great excitement, that an engineer working at the Courtaulds rayon plant north of the city had found evidence of the colonial town. A few days later, I found myself in the woods behind the plant as the engineer, James “Buddy” Parnell, showed me low clay platforms, remnants of French buildings barely discernible beneath the leaves covering the forest floor. My shell mound study would have to wait. Buddy had discovered the archaeological site of Old Mobile, a feat no professional archaeologist had accomplished, and he shared his discovery with us all, thereby insuring the historic site’s study and preservation.

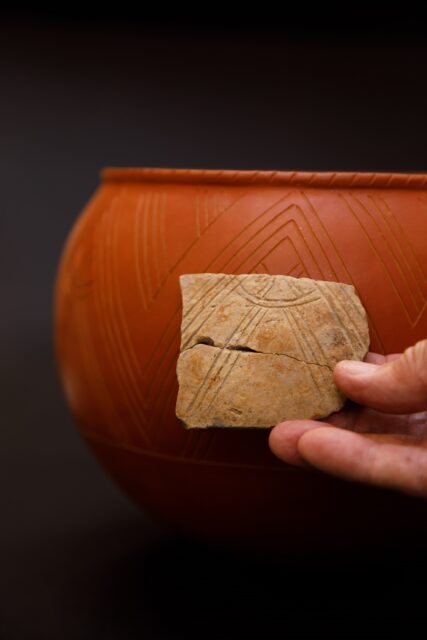

Gregory Waselkov holds a fragment of Native pottery in front of a reconstruction of how the intact vessel likely looked. Photo by Brian Pavlich.

Archaeologists setting out to study French colonial sites in Louisiana must contend with some formidable challenges. Colonial New Orleans is pretty effectively sealed under a great modern city that only occasionally permits narrow glimpses beneath the buildings and pavement of the French Quarter. Searches elsewhere for colonial forts and concessions are hindered by three hundred years of shifting river channels that have eroded some sites and buried others beneath flood deposits. By contrast, at Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff an entire colonial town—in fact, the first colonial town in this region—exists in near pristine condition, with few impediments to researchers. There is no better place to study Louisiana’s French colonial origins than at Old Mobile.

For twenty-nine years I directed the Old Mobile Project with a large team of researchers. Modern archaeology involves collaboration in field and laboratory. Hundreds of students, staff, and volunteers enjoyed the privilege of exploring the townsite during university field methods courses and grant-funded field work. Our most laborious task involved digging and screening the soil from fifteen thousand small test pits arrayed across the site on a four-meter grid, a process that took four years. Systematically plotting the thousands of artifacts recovered from shovel tests revealed the town’s layout on the ground. It turns out that neither of the two surviving historic maps of Old Mobile, which date to 1702 and 1704, precisely match our archaeological findings. Presumably the first map, which is the least accurate, served as a proposal for town development, whereas the more reliable second map documents the town as it existed midway through the French occupation of Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff.

We carried out detailed excavations where our shovel tests told us ten structures had once stood. In every instance we uncovered structural evidence, such as nails, bricks, roof tiles, organic soil stains left by rotting wooden sills and palisade-style fences, and, on occasion, clay platforms like the ones noted by sharp-eyed Buddy Parnell. Correlating our archaeological site plan with the 1704 town map enabled us to identify the residents of five private homes. The largest house, a long and impressive half-timber building at the west edge of town, belonged to two Montreal-born brothers, Joseph and Louis Chauvin. The other structures—a blacksmith shop on Seminary of Foreign Missions property, an Indigenous-style house apparently occupied by Mobilians at the town’s outskirts, and three soldiers’ barracks erected in the parade ground next to Fort Louis—illuminate the diversity of colonial society at Old Mobile.

Part of a ceramic candlestick. Photo by Brian Pavlich.

Nearly all the original settlers who first arrived with Iberville’s fleets were ethnic French, about evenly divided between continental French and Canadians, along with a handful of colonists from Saint-Domingue (Haiti). Arrival of the supply ship Pélican in 1704 added twenty-three French women to the male-dominated community, which quickly diversified ethnically as well. By 1707 two enslaved Africans, husband and wife, whom Bienville called Jorgé and Amarie, labored in Bienville’s household as servants. Many colonists purchased Native American captives from the Mobilians. Totaling eighty by 1708, they ostensibly served as cooks and housekeepers. Roulleaux, the Seminary priest, complained bitterly to his superiors in France about his inability to protect these people—primarily teenaged boys and young women—from abuse by enslavers, typically single French men.

Archaeology provides abundant evidence for the presence of Native Americans in this fledgling French colony. Native-made pottery makes up fully half of the artifacts recovered from Old Mobile excavations. European-made glazed pottery was always in short supply, while local unglazed pottery was readily at hand. Mobilian and Tomeh women created large Native-style cooking jars and spectacular globular bowls, some coated with a red clay slip, that found their way into colonial households. Apalachee potters fashioned copies of European-style plates and pitchers specifically for sale to the colonists, a skill they acquired in their Florida homeland before fleeing slave raids in 1704. French reliance on Native Americans for much of their food and the labor of Native women in many French households probably explains why Native-made pottery played such a prominent role in colonial kitchens.

Another reminder of the prominence of Native Americans in the colonial town takes the form of thousands of small glass beads found at the excavated building sites. These colorful ornaments were manufactured in vast quantities at Italian, Dutch, and Bavarian glasshouses for trade by European colonists all over the world. The presence of so many lost beads at every excavated house and barracks at Old Mobile suggests that each household traded directly with members of the petites nations. By exchanging cloth, steel knives and axes, muskets, and strands of beads for pots, deerskins, and furs, as well as maize and venison, every colonist could eat well and accumulate wealth. In turn, the colonists’ Indigenous trade partners acquired items they desired, but could not manufacture, in exchange for common forest products and items they easily made or grew. Natives and newcomers experienced relative economic and demographic (but not social) parity during this early colonial period. Between 1702 and 1711, a visitor strolling the streets of Mobile would have seen about as many Native Americans, free and enslaved, as colonists in the French colonial capital.

This double-walled cup was made of blanc de chine porcelain in Dehua, Fujian, China. Photo by Brian Pavlich.

Perhaps the most startling archaeological discovery at Old Mobile came in the lovely forms of imported Chinese porcelain encountered at every colonist’s residence. At the dawn of the eighteenth century, in contrast, only the wealthiest households in Europe had access to porcelain. The Spanish Crown tightly controlled trade in Asian imports, which were transported by galleon across the Pacific Ocean, overland on mules from Acapulco to Veracruz, and thence to Spain. The enterprising French at Old Mobile developed several strategies to intercept this commerce, despite a ban on foreigners in Spanish colonial ports. Some found reasons to visit the nearby Spanish garrison at Pensacola, but the most daring built small sailing vessels and risked imprisonment by entering the port of Veracruz. Smuggling proved highly lucrative, and souvenirs of that illicit trade adorned many a French colonial mantlepiece.

The survival, discovery, and excavation of archaeological Old Mobile has given us a great many new insights into life at the dawn of the colonial era on the northern Gulf Coast. As Jay Higginbotham used to say, Old Mobile is our Jamestown, this region’s first formal colonial town and a place of national historical importance. Indeed, in 2001 the National Park Service determined the site eligible for National Historic Landmark status in recognition of Old Mobile’s outstanding historical significance. Fortunately, Mobile County and FMC Corporation, the current owners of Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff, agree and have donated preservation easements on their properties to The Archaeological Conservancy, thereby insuring the townsite’s future protection. There is still so much to learn from this remarkable survivor of Louisiane’s earliest days.

Gregory A. Waselkov is emeritus professor of anthropology and former director of the Center for Archaeological Studies at the University of South Alabama in Mobile. His recent writings include the books Native American Log Cabins in the Southeast and Bears: Archaeological and Ethnohistorical Perspectives in Native Eastern North America, and an article on an Alabama coastal canal dating to 600 CE.