On the Shapes of Parishes

. . . and why Tangipahoa is elongated

Published: December 1, 2024

Last Updated: February 28, 2025

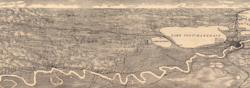

Grand Trunk Railroad, connecting Amite City, Independence, Tickfaw, and Pontchatoula in Tangipahoa Parish with Manchac and New Orleans (far right), 1884.

Library of Congress

Of all sixty-four Louisiana parishes, Tangipahoa Parish stands alone in the origin of its shape. To understand why, it helps to see how geographers have classified the morphology of political jurisdictions, be they nations, states, counties, or in Louisiana, parishes. Those classifications include compact, prorupted (that is, protruding), elongated, fragmented, and perforated (“doughnut”) shapes.

The majority of Louisiana’s parishes may be described as compact polygons—that is, squarish or roundish, and more or less consistently distanced from their centers to their perimeters. Most parishes in northern Louisiana are compact—Claiborne, Union, Bienville, Jackson, Ouachita, to name a few—as are some in the southwest, such as Acadia and Evangeline. Both geography and history supported such configurations, because terrace and prairie environments tend to accommodate compact shapes better than fractured coastal or meandering riverine environs. Their late vintage—most of these parishes were created during or after Reconstruction—tended to put delineation in the hands of state legislators, and what resulted were rather arbitrary compact shapes with straight lines and right angles.

The older areas of southeastern Louisiana, on the other hand, tended to yield protruding shapes. From the colonial perspective, the region’s deltaic geography rendered spaces with highly skewed values, with fertile ridges fronting the Mississippi and its distributaries, and “worthless” swamps and marshes to their rears. Orleans, St. Bernard, Jefferson, Plaquemines, Lafourche, and Terrebonne all exhibit these river-to-sea/bayou-to-bay topographic “slices,” and they came upon our map generations prior to those compact interior parishes of the late 1800s. (See “Why Is Grand Isle in Jefferson Parish? Notes on Parish Topography,” in the Summer 2023 issue of 64 Parishes.) To this day, most residents of prorupted parishes occupy their riverine frontages, and most of their rears remain marsh. Scaling up globally, their shapes resemble those of Thailand or Namibia, in which most people inhabit useful lands at one end of the unit, and very few occupy the other.

Louisiana’s parishes offer no examples of the strangest political shape, the perforated variety, in which one entity completely envelopes another, as the nation of South Africa surrounds Lesotho. Unlike nation-states potentially born of conflict, parishes and counties are intra-state civil jurisdictions, and it would be rather irrational for authorities to complicate their jobs by creating such an eccentric shape.

Relatedly, we have only one fragmented parish—that is, broken into separate units, like Michigan. Likely the result of a surveying error, St. Martin Parish—which otherwise would have been prorupted—ended up getting its lightly populated fringe severed by Iberia Parish’s similarly empty tail.

However, if we consider hydrological interruptions, the number of fragmented parishes grows to include all those that straddle waterbodies. Over thirty miles of open gulf water separate St. Bernard Parish’s Chandeleur Islands from its mainland, whereas only six terrestrial miles separate the two units of St. Martin Parish.

The rest of our parishes are elongated (also known as attenuated), meaning a line drawn lengthwise is significantly longer than one drawn crosswise. Among nations, Chile is the world’s best example of an elongated shape; among parishes, Cameron and Tangipahoa are our best examples. Three times longer east–west than it is north–south, Cameron’s shape can be explained by its position along the Chenier Plain, such that when Cameron was carved out of Calcasieu and Vermilion parishes in 1870, the horizontality of the chenier lent itself to an elongated delineation. Like most other parishes, Cameron’s shape thus reflects human (political) geography reacting to physical geography.

Which brings us to the special case of Tangipahoa Parish. Created from land “out of the contiguous portions of the parishes of Washington, St. Tammany, St. Helena, and Livingston,” Louisiana Act 85 of March 6, 1869 went on to describe the various boundaries of the jurisdiction “to be called and known as the parish of Tangipahoa,” along with its parish seat (Amite City), governance (by police jury), wards, taxes, and so forth. But we have to look to other sources to explain Tangipahoa’s elongated shape, which measures nearly 50 miles north-to-south and only 12 to 18 miles in width.

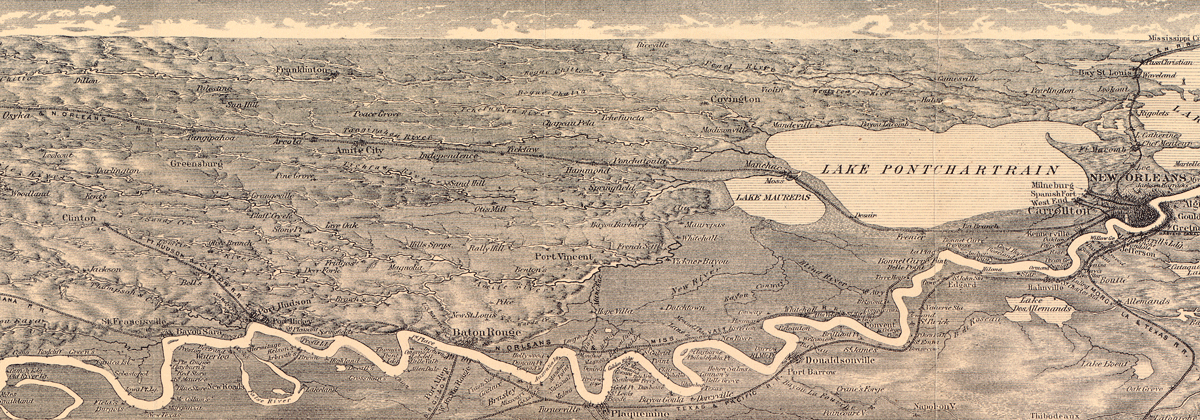

Louisiana parish boundaries and topography, 1966. US Geological Survey

The answer: it followed a railroad. Tangipahoa is the premier example of a Louisiana parish outlined along the trajectory of a private arterial system.

The idea emerged during the heyday of “railroad fever,” when the Pontchartrain (1831) and New Orleans & Carrollton (1835) lines proved profitable in moving freight and passengers over short distances. Investors envisioned a much longer line heading westward of New Orleans, northward up the Manchac land bridge, and across the Florida parishes toward Jackson, Mississippi, and beyond. The Panic of 1837 delayed the project until 1851, when investors from Illinois teamed with locals to form the New Orleans, Jackson & Great Northern Railroad Company (NOJ&GN). In 1853, workers began building the track bed and laying rails up to the Mississippi state line, and by the next year, the region’s first interstate railroad opened up a “grand trunk” through what was then Livingston and St. Helena Parishes—hence the line’s nickname, the Grand Trunk Railroad.

In this all-but-unnavigable part of the Florida parishes, up to now served only by crude backcountry roads, folks seemed to sense the NOJ&GN would change everything. Among them was a group of giddy journalists from the Daily Picayune who in September 1855 joined the company president for a junket up the Grand Trunk. Extolling the “verdure” and “delicate flowers of every hue,” the journalists noted the new communities spawning almost overnight along the artery. Among them were “Kennersville,” now Old Town Kenner in Jefferson Parish, followed by “Frenier” in St. John the Baptist Parish. Up the land bridge over Pass Manchac brought the journalists to “Ponchatoula station, forty-seven miles from the city,” gateway to the “far famed ‘Piney Woods.’’’ Next came “Tickfaw” followed by “the pretty and flourishing village of Amite” with “its inviting hotel [and] fine steam saw mill”; then on to “Tangipaho station,” its depot full of “waiting passengers, and of freight of all kinds: oxen and wagons, laden with cotton,” and finally Osyka, across the Mississippi state line. “A more pleasant day is rarely spent on such an excursion,” the journalist concluded. “Success, we say, to the Grand Trunk Railroad.”

Tangipahoa is the premier example of a Louisiana parish outlined along the trajectory of a private arterial system.

The enthusiasm continued a few years later, when in 1861 two investors acquired track-side land owned by Peter Hammond to establish the C. E. Cate & Company shoe factory and lumber mill—thus giving rise to Hammond, now the largest city in Tangipahoa Parish. In this manner, an axis of people and products on the move had been blazed through bucolic woodlands, and suddenly there were towns, timber mills, and farms arising all up and down the line. The area benefitted additionally when Confederate commanders established Camp Moore by “Tangipaho station,” to train soldiers for the impending Civil War. In 1862, Cate & Company won a contract to supply footwear for the Confederacy, and soon both Hammond and the NOJ&GN bustled with action.

But after Union troops captured New Orleans, the Grand Trunk became a prime target, as did the shoe factory and Camp Moore. By 1863, all were in ruins.

The war, or rather its political aftermath, laid the groundwork for the creation of new parishes—most of them compact, some elongated. In seeking control of state government over Democrats dominated by former Confederates, federally backed Republicans adopted the tactic of carving out new parishes to augment their political support. Nine new parishes were created during 1868 through 1877, and with them came new seats of governance and justice, usually staffed with political appointees. Among the new jurisdictions was Tangipahoa Parish, and while the 1869 legislative act is mum on the “why” of the shape, it’s plain to see that the Grand Trunk Railroad, by this time being rebuilt, was the axial prize imparting value to this elongated swath of piney woods.

In 1874, the tracks came under the control of the New Orleans, St. Louis & Chicago line, and four years later, the Illinois Central. In 1885, the Illinois Central began recruiting Midwestern farming families to settle in fertile Tangipahoa Parish, in the hope that they would soon become passengers and produce-shippers on its trains. They were later joined by Sicilian immigrants, who used the line to ride up from New Orleans and establish truck farms to supply market stalls staffed by their urban brethren. Soon the region became a produce and dairy hotspot, known particularly for its strawberries and milk products, and new communities arose at regular increments along the tracks. Midway between Hammond and Tickfaw, for example, formed the trackside settlement of Natalbany; halfway between Tickfaw and Amite sprouted Independence (now home to the Sicilian Heritage Festival); evenly distributed between Amite and Tangipahoa were Roseland and Fluker; and midway between Tangipahoa and Osyka was Kentwood.

In the twentieth century, modern highways were built along the general trajectory of the railroad, and in certain segments, within the tracks’ right-of-way. Fully ten communities emerged along the tracks or the spur lines emanating from its stations, and together this elongated corridor served by Highway 51 and Interstate 55 now accounts for one-third of the Tangipahoa Parish population of 137,000 people. Without that 1850s decision to route the Grand Trunk Railroad, Tangipahoa Parish would have quite a different look today—and probably a different shape.

You can still experience the journey today by riding Amtrak’s famed “City of New Orleans” service to Chicago—clear through all fifty miles of elongated Tangipahoa Parish, with a stop in Hammond.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Draining New Orleans, The West Bank of Greater New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on X.