Spring 2023

Sportsman’s Paradise, or Paradise Lost?

The Toledo Bend Reservoir

Published: February 28, 2023

Last Updated: June 1, 2023

Richard Campanella

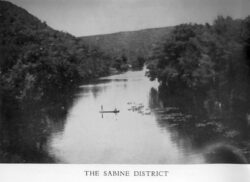

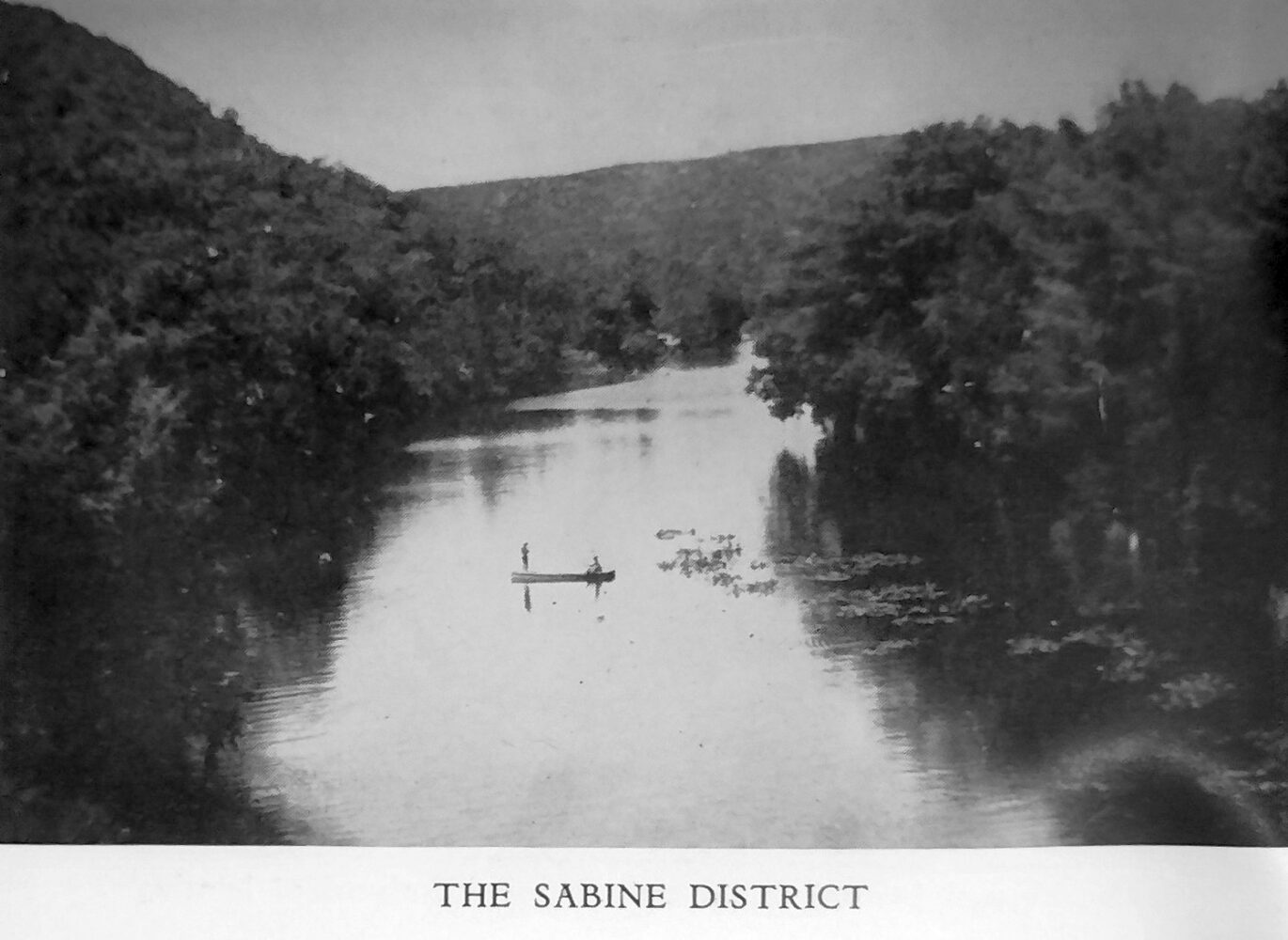

“The Sabine District” from Louisiana Out-of-Doors by Percy Viosca.

“Wow,” I said. “That’s in Louisiana?”

I came across this image while paging through a dogeared copy of Louisiana Out-of-Doors—A Handbook and Guide (1933), a labor of love self-published by famed biologist Percy Viosca Jr. and written in the tone of a scoutmaster who curbs his sportsman’s-paradise enthusiasm with conservationist responsibility. Viosca captioned the gray-tone photo simply as “THE SABINE DISTRICT,” and after a little scouting around of my own, I surmised it had been taken along the Texas–Louisiana border before that stretch of the Sabine River had been dammed to form the Toledo Bend Reservoir.

That’s why I had not recognized the vista: half of it has been under water for as long as I’ve been alive.

The Toledo Bend Reservoir reflects Louisiana’s largest and most draconian transformation of contiguous landscape traceable to a single project. The waterbody, shaped rather like an alligator—or is it a centipede?—jumps out from any map, swimming down our western border with a length of well over fifty miles and a width of three to five miles, double across its tributary “legs.”

The distinctive shape traces the morphology of the Sabine River basin, a narrow watershed originating just east of Dallas and bending southeastwardly to discharge into the Gulf of Mexico. Sabine meaning “cypress” in Spanish, the sluggish river and its swampy bottomlands wended through that swath of Caddo indigenous territory that found itself on the margins of Spanish colonial possessions to the west as well as French claims to the east, namely Louisiana. When France sold Louisiana to the Americans, the eastern flank of the Sabine basin became known as the Neutral Ground, or Sabine Free State, an ungoverned realm between Spanish Mexico and the United States where the displaced and the marginalized held sway.

The river itself partly accounted for the region’s roguish repute: tough to navigate, prone to overflow, and lacking in arable banks, the Sabine attracted few significant human settlements, and to this day hosts only a few sizable bankside communities, among them Logansport, Louisiana, and Orange, Texas. Along with the 31st parallel, the Sabine River became the last Louisiana border segment to fall into place, when in 1819 the United States and Spain signed the Adams–Onís Treaty, or Florida Purchase. Once at the extreme southwestern frontier of the United States, the old Neutral Ground eventually became today’s Vernon, Beauregard, Calcasieu, and Cameron Parishes.

Yet even a century later, not much had changed along the Sabine. In “Water and Power: The Sabine River Authority of Louisiana,” published in 2012 by the Tulane Environmental Law Journal, legal researcher and archeologist Ryan M. Seidemann notes, “The River remained largely untamed and forgotten in the timberlands of East Texas and West Louisiana until, in the 1930s, political rumblings began about converting the River to a water conservation area and a recreational destination.”

Appeals for damming the Sabine grew louder after World War II, when the chemical industry called for a large reliable supply of fresh water to process acids and hydrocarbons in coastal Texas.

Advocates formed the Sabine River Watershed Association, followed by the 1949–1950 creation of the Sabine River Authority of Texas and the Sabine River Authority of Louisiana—legal bodies “with sweeping powers,” writes Seidemann, and unusual autonomy from other state agencies. Because this project crossed state borders, Texas and Louisiana signed a compact to stipulate how resources and expenses would be shared. By the time Congress ratified the compact in 1954, a fourth goal had been added to the project: hydropower, courtesy of the impressive hydraulic head yielded by the rugged Sabine Uplift topography apparent in Viosca’s photograph. Once that valuable energy source became clear, the Sabine’s wild days were numbered, as the dual authorities envisioned a number of dams and reservoirs along the waterway.

The timing was not unusual: this midcentury era marked the zenith of American dam-building and land reclamation, with most major reservoirs created between the 1930s and the 1970s. What was unusual about the Sabine project was the minimal involvement of the federal government, traceable to an unfavorable feasibility study released by the US Army Corps of Engineers in the 1930s. The rebuff left it up to the two state governments to pay for the project, and the two SRAs to oversee site preparation, construction, and operations. This was truly regional development, and its Louisiana champion was State Representative Cliff Ammons of the Sabine Parish seat of Many. A one-time opponent whose family stood to lose land to the project, Ammons read studies of the reservoir’s potential benefits, became an ardent supporter, and later earned the honorific of “the Father of Toledo Bend.”

According to Bob Bowman, author of The Gift of Las Sabinas: The History of the Sabine River Authority, 1949–1999, funding from Texas came from a state legislative appropriation, while voters in Louisiana passed a constitutional amendment in 1960 permitting the rededication of a Confederate veterans pension fund to start paying for the reservoir. (The state had millions of dollars in the fund but only one surviving Confederate widow.) Both Texas and Louisiana also sold bonds to the utilities that would transmit the electrical power to be generated. Soon, they amassed $30 million for the project, and eventually spent double that sum.

Over the next four years, the two SRAs purchased or expropriated hundreds of private properties and relocated four hundred families who resided between the natural banks of the Sabine and its tributaries up to the 172-foot contour. The displacements were a contentious and culturally destructive process, obliterating communities with names like Pine Flat, Kites Landing, and Richard Neck, and incurring years’ worth of litigation as well as lasting bitterness. Among the displaced were members of the Choctaw–Apache Tribe, themselves descendants of the forcibly displaced Choctaw to the east and Apache to the west.

. . . voters in Louisiana passed a constitutional amendment in 1960 permitting the rededication of a Confederate veterans pension fund to start paying for the reservoir. (The state had millions of dollars in the fund but only one surviving Confederate widow.)

Another targeted settlement stood astride a particularly circuitous bend in the Sabine just below the main proposed dam site, an area on the Texas side deemed too risky to occupy. It comprised a handful of families, a school, and a cemetery, and went by the name of Toledo, where a man named A. M. Bevil had attained a land grant in the 1830s and went on to operate Bevil’s Ferry. Because engineers in the 1930s had determined this narrow valley to be the optimal dam site, they dubbed the project “Toledo Bend,” and the name stuck—even as Toledo, Texas, was obliterated. (Why Toledo? Four theories circulate, all conjectural: because in Spanish toledo meant songbird, of which there were many here, though the word is unfamiliar to modern Spanish speakers; because missionaries who came from Toledo, Spain, thought this bend of the Sabine resembled a meander of the Río Tajo; because of a Spanish writer or local land grantee named Toledo; or because the Bevils hailed from Toledo, Ohio.)

In 1964, work began on the 1.6-mile-long earthen dam—the highest, straightest levee you’ll ever see—and in October 1966 the embankment began impounding the waters that would eventually cover 186,000 acres and form a shoreline 1,200 miles long, with a maximum depth of 99 feet. Turbines and power facilities were installed over the next two years, as were new roads and recreational facilities, and in 1969, Toledo Bend Reservoir opened for electrical generation and public recreation.

Today Toledo Bend ranks as the largest manmade reservoir in the South, fifth largest in the nation, and the only one of its magnitude to not involve significant federal funding. It generates 205 million kilowatt-hours of electricity annually, along with tens of millions in recreational dollars, drawing vacationers, retirees, and weekend warriors chasing legendary large-mouth bass. “Toledo Bend,” concludes writer Andy Crawford in Louisiana Sportsman, “is a godsend to this part of the world.” The vast waterbody also prompted a wholesale reconfiguration of transportation, communities, and businesses over some six hundred square miles, principally in Sabine Parish.

Much has been gained in the making of Toledo Bend Reservoir, including abundant clean energy and a lucrative recreation industry in a region with few other economic options. But enumerating the benefits obligates us to also tally up costs, one of which was that beautiful hillside scene captured in Viosca’s book.

It must have been sometime in late 1966 or early 1967 when the rising reservoir inundated that idyllic locale. Along with it went thousands of acres of rich riparian habitat and verdant bottomlands, archeological sites ranging from prehistoric Caddo homelands to the Civil War–era Sabine Breastworks, and the former spaces and places of hundreds of Louisianans. Inspecting US Geological Survey topographic maps from the 1940s, I believe that photo could have been taken in any one of three or four spots where unusually steep hills (up to 250 feet above sea level—alas, all on the Texas side) plunged down to the Sabine, whose elevation below the dam site was around one hundred feet. Flood that basin up to the 172-foot contour, and our Nirvana disappears by half, which is exactly what you’d see if you attained the same perspective today.

I am left to wonder how Percy Viosca himself, renowned Louisiana biologist and leading conservationist, would have judged the Toledo Bend Reservoir: sportsman’s paradise, or paradise lost?

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Draining New Orleans (LSU Press, 2023), The West Bank of Greater New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, and other books. He may be reached through http://richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on Twitter.