Louisiana Hill Country

Not so high and mighty

Published: August 31, 2021

Last Updated: December 1, 2021

Photo by William Dillingham, Alamy Images

And yet topography factors fundamentally, if not deterministically, into cultural variations within our state. When we speak of “the Acadian Triangle,” we are indirectly inferring topography, as this region that is more Cajun, Catholic, Creole, and Francophone than the rest of the state is also more riverine, deltaic, and estuarine.

Conversely, the more Protestant and Anglo-Saxon parishes tend to be more topographically undulating, be they the ancient hills of the northwest, the central terraces, or the silty loess bluffs lining the Mississippi River alluvial valley. Relatedly, the distribution of African Americans in rural Louisiana largely correlates to the geography of former plantation regions—flat, fertile, riverine areas—and diminishes precipitously as the terrain gets rugged.

Sometimes these topographic/cultural regions practically abut. Consider the very Anglo historic town of St. Francisville, once in British West Florida, sitting atop scenic bluffs in West Feliciana Parish, and contrast it to Pointe Coupee Parish just across the Mississippi, whose ethnic stock is more likely to have French blood, whose cemeteries are above ground, whose churches are more likely to be Catholic, and whose land is generally surveyed into French long lots, as opposed to American square sections or irregular British metes and bounds. The two parishes are minutes apart, driving over the Audubon Bridge. African American populations are high in both areas, because both had fertile terrain, and thus plantation legacies.

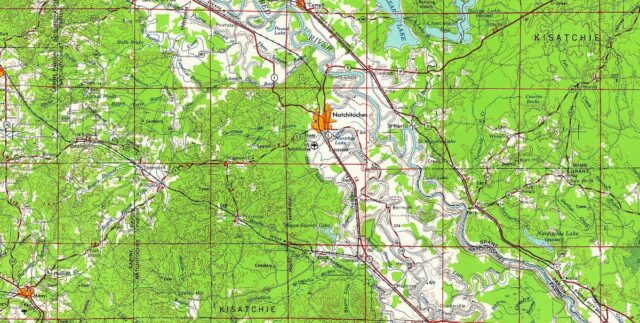

Consider also Natchitoches along the fertile Cane River/Red River Valley, where you’ll find yourself in old French Creole country, with Creole architecture and French long-lot plantations, amid a prevailing lower-Louisiana aura despite its latitude. But drive just a few miles to the west, and you’re in hilly pine woodlands, in more of an interior-South cultural milieu. Farmers here historically were more likely to be independent small land-owners (yeomen) who raised food crops and livestock for local consumption—what historian Frank Lawrence Owsley called the “plain folk of the Old South,” far different from the commodity plantations worked by enslaved laborers along the Red River. Latitudinally, both areas are in northern Louisiana, but topographically, historically, and culturally, they’re different worlds.

To the 400,000-plus folks who live in the uplands… pine-covered hills and red clay terraces feel like Louisiana.

Let’s take a closer look at the physical geography underlying these Louisiana upland cultures, starting in the so-called Florida Parishes—that is, from West Feliciana Parish east to Washington Parish, south of the Southern Mississippi Uplift. These gentle hills are known as the Pleistocene Terrace, a two-million-year-old surface of hard clays originally covered with longleaf or loblolly pine savannas. Pushing up on the terrain from below are the Bentley and Montgomery Formations, which have raised some crests to over 350 feet above sea level in northern St. Helena, Tangipahoa, and Washington Parishes. It’s our highest terrain south of the 31st parallel, particularly striking for its proximity to the lowest spot in Louisiana, in eastern New Orleans, 10 to 14 feet below sea level. These piney woods have a forestry-based economy dominated by tree farms, and Bogalusa has long been the region’s premier example of an industrial mill town, producing paper and wood products. In these pine-covered hills east of the Amite River, commodity agriculture is rare; there were few plantations here historically, and antebellum architecture is scarce. Cultural folkways here tilted more toward the interior South hundreds of miles to the north, rather than toward the coastal plain, “south of the South,” just fifty miles away.

To wit: the ambience at the famous Washington Parish Free Fair in Franklinton every October can easily pass for central Mississippi or even Tennessee, with its bluegrass music, country-style foods, and frontier-style log-cabin heritage exhibits. And if you really want a topographic surprise, head north just over the state line, to Red Bluff, where an escarpment in the clay terrace above the Pearl River has created a truly impressive feature known locally as “the Grand Canyon of Mississippi.” Parts of it look like rock formations in Utah—within a hundred miles of deltaic New Orleans.

West of the Amite River, in the Feliciana Parishes, the geophysical conditions change, and that too would affect the economy and culture. Here, a layer of windblown silt known as loess (a German term implying “loose”), deposited after the Ice Age, brought fertility to this part of the Pleistocene Terrace. With fertility came hardwood forests, cotton plantations, slavery, and the many antebellum buildings still standing in towns like Clinton, Jackson, and St. Francisville. (Natchez, Port Gibson, and Vicksburg also sit on loess terrain, and have similar economies, cultures, and architectural histories.) Much loess has since eroded away, due to poor soil conservation practices—some gullies are downright rugged, with steep drop-offs almost like cliffs—and what were once croplands are now typically forests and pastures. Whereas most loess deposits accumulated east of the lower Mississippi Valley, some fell within the floodplain or to its west, accounting for the Macon Ridge and Bastrop Hills in Morehouse, West Carroll, and East Carroll Parishes.

Now let’s head to the uplands of the opposite corner of the state, home to Driskill Mountain. Geographically, topographically, and culturally speaking, you can’t get any further from, or higher above, the lower-delta country and still be within Louisiana. These northwestern parishes are also distinct from the upper reaches of the adjacent Acadian Triangle, being on the meat-and-potatoes side of what some people jokingly call the “boudin curtain.”

Topographical map of the Kisatchie Hills region, with Natchitoches visible near the center. United States Geological Survey

As if to speak to these uplands’ predominant Scotts-Irish/Anglo-Saxon demographic as well as their historical proximity to Spanish Mexico, the geological terms wold (British) and cuesta (Spanish) are used to describe the 300-to-500-foot ridges on both sides of the intersecting Red River Valley. “Wold” is an old English term meaning a wooded upland, and “cuesta” (literally, “cost”; figuratively, an incline), according to the Oxford Dictionary of Geology and Earth Sciences, is an “asymmetric land-form consisting of a steep scarp slope, and a more gentle dip (or back) slope[,] typical of areas underlain by strata of varying resistance that are dipping gently in one direction,” in our case toward the coastal plain. The late Louisiana geographers Fred Kniffen and Sam Hilliard described the Kisatchie Wold, the Nacogdoches Wold, and the Sabine Uplift as “sedimentary rocks [stacked] like a tilted deck of cards, with younger beds overlaying older layers,” together forming “true solid rock . . . the oldest rocks in the state,” around 50 million years of age.

Here and only here in Louisiana can you find rocky outcroppings, babbling brooks with stones and boulders, and panoramic vistas of gentle pine-covered hills disappearing into the horizon. Here may be found Louisiana’s most rugged parishes: Lincoln, by my calculations, has an 0.46-degree average slope, and Claiborne (our highest parish, with a mean elevation of 267 feet above sea level), averages an 0.43-degree slope. For comparison, all coastal parishes are in the 0 to 0.02 range. Northwestern Louisiana is also home to the state’s only US Forest Service jurisdiction, Kisatchie National Forest, and our only federally designated wildlands area, the 8,700-acre Kisatchie Hills Wilderness, where no development, roads, or mechanized vehicles are permitted. Except for the Red River Valley, whose soils are younger and more fertile, these fifteen parishes are timber country, and more recently, oil and gas.

To hike Kisatchie’s hills and climb their rocky outcroppings is to feel like you’re in Arkansas or Texas—but then again, perhaps only if, like me, you live in Louisiana lowlands. To the 400,000-plus folks who live in the uplands, roughly ten percent of the Pelican State’s population, pine-covered hills and red clay terraces feel like Louisiana, and the coastal lowlands to their south, with their Cajuns, Creoles, Catholics, and curious cuisine, may feel like that’s the place that’s apart.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of The West Bank of Greater New Orleans, Cityscapes of New Orleans, Bienville’s Dilemma, and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, [email protected], or @nolacampanella on Twitter.