That’s a Mighty Fine Tomato

Creole tomatoes and the women who love them

Published: February 29, 2024

Last Updated: June 1, 2024

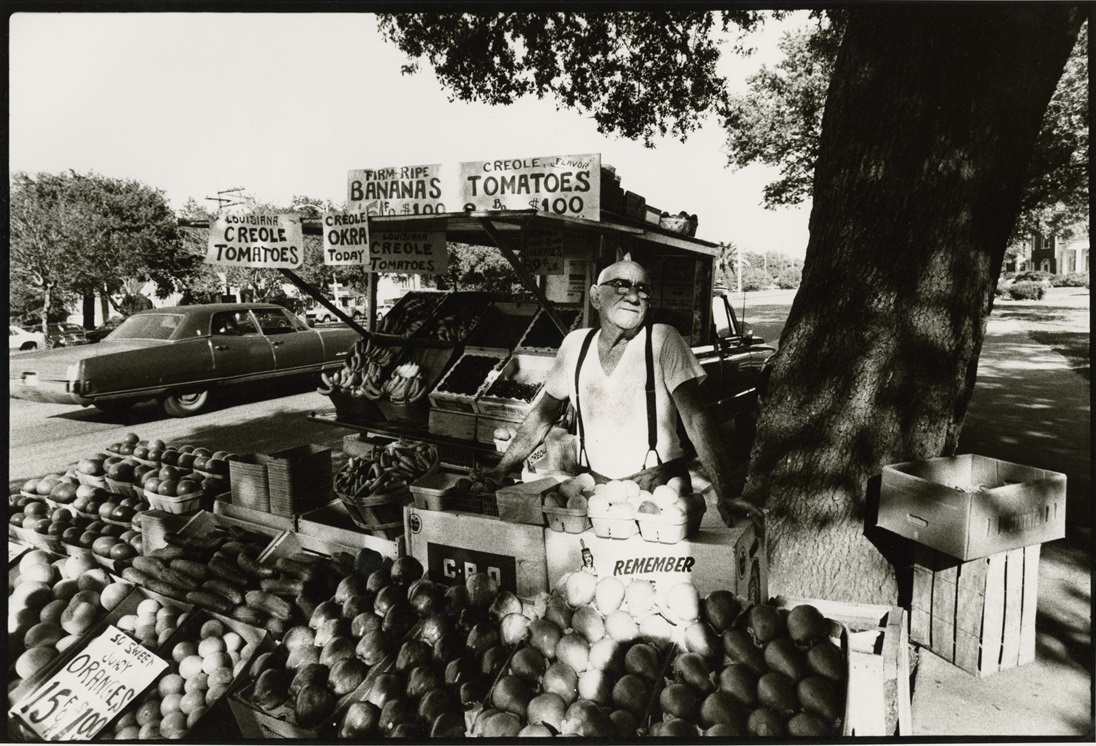

Photo by Josephine Sacabo, The Historic New Orleans Collection

A vendor sells creole tomatoes and other produce near the intersection of South Claiborne and Nashville Avenues, 1975.

A ruby on my tongue

Seed pearls between my teeth

The stems are the veins of my garden

The fruits the heart.”

So reads the writing that spirals on the edges of the artwork hanging next to my bed in New Orleans. The work, by Mississippi native Blair Hobbs, is entitled Creole Love Apples and features a collage of a smiling Creole woman with tomatoes for breasts. I fell in love with the piece several decades ago.

I have long been a firm partisan of summer-ripe tomatoes fresh from the vine. In my northern guise, I grow them in my garden and delight in eating salads and sandwiches made from freshly plucked ones all summer long. As a purist, I go without fresh tomatoes in the cooler months because the odorless, colorless, cottony, hard ones that are available in my supermarket just don’t make the cut. I await the return of ripe tomatoes and search them out with the anticipation of a crusader questing for the Holy Grail. It’s no surprise then, that when I purchased a house in New Orleans, I would fall under the spell of Creole tomatoes.

I knew a fair bit about tomatoes. I knew that they originated in the Americas around seven thousand years ago, and that they had been brought to Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, where they were looked at as decorative but poisonous. I was amazed to learn that they were only widely eaten in the United States after the Civil War—their consumption aided by the habits of those who migrated here from southern Europe, where tomatoes were by then part of the traditional diet. I knew about the farm-fresh beefsteak tomatoes of New Jersey and the summer delights that I grew and found in the roadside stands of Martha’s Vineyard. But I had never heard of the wondrous Creole globes until I arrived in the Crescent City.

Creole tomatoes are difficult to define; it turns out that the Louisiana Department of Agriculture and Forestry has not regulated the name. While there are specific varieties of tomato that are marketed as Creole, they may not be the ones that are found in farmers’ markets and local supermarkets all over southern Louisiana. It seems that the Creole tomato sold in southern Louisiana markets and celebrated at the New Orleans French Market Creole Tomato Festival is as elusively magical as the image over my bed. Creoles, it seems, are the result of the alchemical combination of the dense clayey alluvial soil of southern Louisiana, the water of the Mississippi River, and the late spring sunshine. They can only truly grow in the special terroir that exists in Saint Bernard and Plaquemines Parishes downriver from New Orleans, although that area has now been expanded somewhat to include parts of the North Shore. The season usually runs from May until January, but according to local growers, it depends on when (and if) we get a freeze. Dan Gill, a horticulturist with the LSU AgCenter and Nola.com garden columnist, says, “Any locally grown red, medium to large tomato is a Creole tomato regardless of cultivar.” In short, if they ain’t from here, they ain’t Creoles, and if they are, they are. You can take the same plant and grow it in Mississippi or New Jersey, and you’ll get a lovely tomato, but it will most assuredly not be a Creole tomato or have its special qualities.

I have learned to wait and look for the arrival of the special cardboard boxes that are marked Louisiana Creole Tomatoes. They are always a bit of a surprise to me, because in other locales, their green-tinged red would indicate unripe status and their often-firm texture might herald toughness. Some are knobby enough to make you raise an eyebrow. I know better now. But even knowing them as I do, I am always amazed and delighted when I slice one open to reveal its dense, juicy lushness.

When the Creoles arrive, restaurants around the city erupt in a frenzy of salads and dishes that show them off to their best advantage. I indulge in them around the clock, often starting the day with fried green Creole along with bacon as breakfast, proceeding on to a sandwich of sliced juicy ripe ones on mayonnaise-slathered white bread for lunch, and ending the day with a cup of gazpacho or a baked stuffed one. Their intense richness, though, seems to lend itself particularly to just slicing and savoring, and I save some for that end, usually dressing them with a light vinaigrette and perhaps a few snippets of fresh basil or spearmint.

I have even discovered that I can successfully transport them over state lines. I now purchase unripe green ones that I swaddle like the baby Jesus, carefully pack inside a plastic bin purchased especially for the purpose, and take them in my carry-on luggage, so that I may indulge in places where the unfortunate populace is ignorant of their existence and their magical properties. Once I have arrived, I parse them out and miserly share them only with friends that I know are tomato lovers of the highest order. We gather around my kitchen table to slice, slurp, and savor the tomatoey delights of the Creole tomatoes that the gods of southern Louisiana have bestowed on the world.

Jessica B. Harris is the author, editor, or translator of eighteen books, including twelve cookbooks documenting the foodways of the African Diaspora. In March of 2020, she became a James Beard Lifetime Achievement awardee.