Fall 2008

The Iberville Stone

The mystery behind one of the Gulf Coast’s oldest colonial relics

Published: October 17, 2022

Last Updated: October 17, 2022

Louisiana State Museum

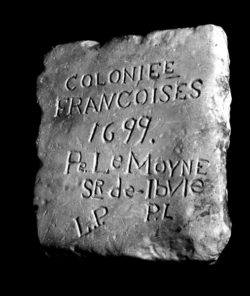

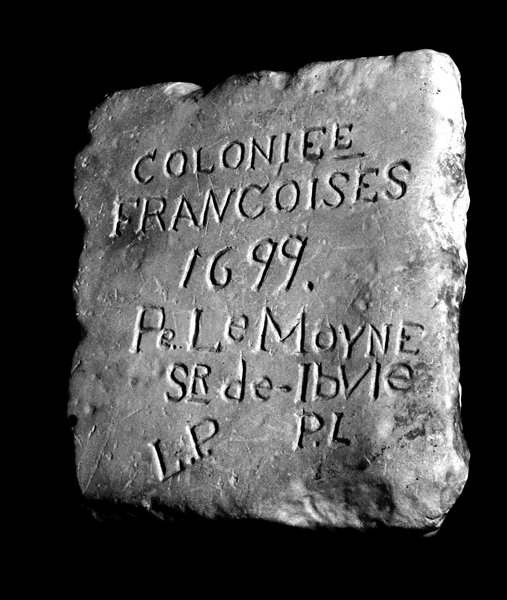

coloniee Francoises 1699.

Pe. LeMoyne Sr de-Ibvle

L.P.P.L.

Until recently the museum’s interpretive label claimed simply that the stone was “recovered from the site of Fort Maurepas, the first permanent settlement established by Iberville in the Mississippi Valley.” However, that seemingly clear and simple interpretation of this chiseled tablet belies the stone’s mysterious and intriguing history. According to historical record, the stone was discovered buried on private property in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, around 1910. Those who support its authenticity argue that Iberville used the stone to mark French occupation of the Mississippi coast in 1699. Yet over the years historians have questioned its authenticity, and many experts have attempted to set the record straight. And even beyond the stone’s provenance, residents of Ocean Springs, where the stone was discovered, have at times alleged that the Louisiana State Museum was not authorized to assume possession of the Iberville Stone in 1937.

Given the questions and historical drama that surround the stone, the Louisiana State Museum has made efforts since the 1930s to authenticate and prove valid ownership. Even with these efforts, much of the stone’s historical mystery remains, and its existence still calls for historical detective work.

Is the stone authentic?

Part of the mystery of the marble plaque known as the Iberville Stone surrounds the discovery and location of the relic. According to a Louisiana State Museum report from 1937, the stone, along with several handmade bricks, was found by Captain Frederick A. Schreiber on the estate of W. B. Schmidt at Old Biloxi, which is present-day Ocean Springs. Since that time, however, it became clear that in fact Robert Rupp, listed as the caretaker of the Schmidt estate, actually dug up the stone, but kept it a secret for many years. Eventually, his son-in-law Frederick A. Schreiber, who was the Austrian lighthouse keeper on Chandeleur Island, acquired the stone and bricks, which he kept safe and out of public view until the mid-1930s. Originally the stone appeared dark from being buried for so long. But when Schreiber was stationed as a keeper for the lighthouse at Madisonville, Louisiana, for some years, he placed the stone beneath the overflow pipe of an artesian well to wash away the discoloration gently and reveal the pale marbled hue.

Eventually, two Ocean Springs residents, Dr. O. L. Bailey and Mrs. O. D. Davidson, sought to publicize the stone’s significance, and in the mid-1930s the weeklong Jackson County Fair in Pascagoula displayed the relics in a special exhibit. Dr. Bailey then displayed the stone and bricks in the window next door to his drugstore in Ocean Springs, where they continued to incite questions about their authenticity. Finally, in 1937, Mrs. Davidson hoped to garner greater publicity for the artifacts by notifying the New Orleans Item newspaper and James A. Fortier, Louisiana State Museum curator and president. Fortier persuaded Schreiber to transport the artifacts to New Orleans, where they could be authenticated more precisely.

After an examination at the Louisiana State Museum using available resources, Fortier claimed that the stone was authentic. In a report he argued that the stone matched the description of other similar stones from the same period and that the inscription also matched those of the era. The bricks found with the stone were the type used in French buildings in the late 1600s, and the location where they were found matched historical accounts of the location of Fort Maurepas in 1699.

However, Fortier’s claims have failed to satisfy historians and curators since that time, and several persons have argued against Fortier’s findings. In 1989, the Louisiana State Museum and several forensics experts made another formal effort to authenticate the stone. Geologists Delbert Gann and David Dockery, along with archaeologists Dr. Patricia Galloway and Dr. Samuel McGahey from Mississippi, studied the marble, examining its age and mineral content. Tulane history professor Charles Carter verified the inscription’s grammar as being consistent with the 1690s. But Galloway raised questions by arguing that “coloniee Francoises” was a common French coin inscription from the mid-1700s and not from the late 1600s, feeding speculation that someone from a later period carved the stone, possibly as a forgery to mark the earlier settlement.

Furthermore, historians of colonial Mississippi are not convinced that the location of the Schmidt estate in Ocean Springs was the actual site of the original Fort Maurepas in 1699. In 1999, several Mississippi archaeologists raised questions about this historical controversy in the journal Mississippi Archaeology. Why is the location important? The stone would have been laid at the site of the original settlement. So proving the site of the original Fort Maurepas would, in theory, help determine the authenticity of the stone.

The archaeologists presented evidence that the Fort Maurepas site was more likely north of the location where the stone was originally found. They cite the work of Schuyler Poitevant, a resident of Ocean Springs who owned property north of the Schmidt estate, where he had discovered a wealth of artifacts related to the first French settlement. From the 1880s to his death in 1936, Poitevant kept very careful records of his discoveries and research, which led the archaeologists to take his findings seriously.

Poitevant actually believed that the stone was an authentic French colonial artifact, but that it was most likely a commemorative marker placed at the site of a French battery established at the time of the first colony. The lack of historical consensus on the location of Fort Maurepas only adds to the overall mystery of the stone.

To make the history even more confusing, Biloxi historian Edmond Boudreaux claims the stone may have been created as a hoax in the early 1900s. According to Boudreaux, sometime in the 1980s an older man from Ocean Springs confided to Dr. Val Hulsey, curator of the Maritime and Seafood Industry Museum in Biloxi, that three or four of his friends made the stone as a prank in their youth. According to the man, the joke got out of hand, and before he died, he wanted to confess.

To whom does the stone belong?

As if the Iberville Stone’s authenticity were not enough of a historical conundrum, the artifact also has a modern history that involves allegations of larceny committed by the Louisiana State Museum in 1937. In the late 1930s Robert Fortier served as curator and president of the Louisiana State Museum. As recounted earlier, in 1937 Dr. Bailey and Mrs. Davidson invited Fortier to view the relics. Upon his visit to Mississippi, Fortier received permission from Frederick A. Schreiber to remove the artifacts to New Orleans for examination. When Fortier confirmed that the stone was, in his opinion, authentic, he made efforts to have the Louisiana State Museum procure it permanently. Since that time some residents of Ocean Springs have claimed that Fortier essentially committed larceny by securing the property without proper title to ownership and then keeping it permanently against the wishes of its proper owners and the town of Ocean Springs.

The controversy stems from the original loan agreement between Fortier, Captain Schreiber, and the Schmidt family (who were the rightful owners) and Dr. Bailey and Mrs. Davidson, who initially encouraged Fortier to take the stone to New Orleans. Louisiana State Museum letters written at the time between the parties illuminate the misunderstandings and delicate negotiations involved. As Fortier explained to Schreiber, the museum had planned on returning the stone to Ocean Springs after thirty days. But according to Fortier “the heirs of the Schmidt estate expressed their great pleasure” at Schreiber’s “turning over” of the plaque to the museum and “stated that it was their wish the plaque remain in the custody of this state institution.”

In the fall of 1937, Fortier asked Schreiber to make his donation to the Louisiana State Museum official. Schreiber wrote the curator a letter in October 1937 confirming his donation. The old Austrian lighthouse keeper, who admitted he was not very educated, claimed, “I, nor any body [sic] owned the stone And that all I wanted it to be used for Historical perperes [sic] only and for no profit to any indevidual [sic].” Complaining that the stone was “un observed and unnoticed” in Ocean Springs for over a year next to Dr. Bailey’s office, Schreiber wrote unequivocally to Fortier, “I SAY LET IT STAY WHERE IT IS NOW. IN GOOD CARE AND IN THE RIGHT PLACE IN THE LA STATE MUSEUM.”

Understanding that Fortier was under pressure from Dr. Bailey to return the stone, Schreiber informed the curator, “I will try to get Dr. Bailey to see it that way.” But Schreiber may not have been immediately successful in this latter endeavor. For years, residents of Ocean Springs felt a sense of injustice over the issue. Today Edmond Boudreaux argues that residents of Ocean Springs have generally come to terms with Schreiber’s donation. Perhaps Fortier did take the objects to Louisiana with a larger agenda than examining them. But Schreiber never envisioned Ocean Springs as having any entitlement to the stone. As he forcefully concluded to Fortier in his letter, “I don’t owe Ocean Springs, or anyone a red cent. no [sic] one has ever shown me any favors or a[n]y kind or gave me anything, And [sic] I never asked for any.”

The mystery remains

Today the Louisiana State Museum is honored to display this unique artifact at the Cabildo, where an updated label now appears. And in the spirit of cooperation, the Louisiana State Museum has offered to assist in making a replica of the stone for the Maritime and Seafood Industry Museum in Biloxi. Boudreaux, who volunteers for that museum, recently acknowledged this attempt at reconciliation: “During the mid-1900s there were a large number of individuals in Ocean Springs who believed that the stone was basically stolen from the family and the City of Ocean Springs. Today you may find some who still feel the same, but I believe the majority would at least like to see a replica of ‘The Iberville Stone’ in a local museum.”

Despite all of the examinations and research, experts have still not definitively proven that the Iberville Stone is authentic—that it is the original French plaque from 1699 marking the site of Fort Maurepas. The stone may have been inscribed in 1699, or it may be a commemorative plaque from the 1720s as the amateur historian Poitevant claimed. Even more disconcerting, though, is the idea that the stone is a hoax from the early 1900s, as the anonymous old man in Biloxi declared. But while the history of the stone ultimately remains unconfirmed, its mystery points to our fascination with objects from the past. The Louisiana State Museum encourages visitors to view the Iberville Stone in the Cabildo, where it still invites speculation about its true history and illustrates how historical research often leaves unresolved questions.