The Other “Undocumented” Workers

Illegal free Black labor in antebellum New Orleans

Published: November 30, 2023

Last Updated: February 29, 2024

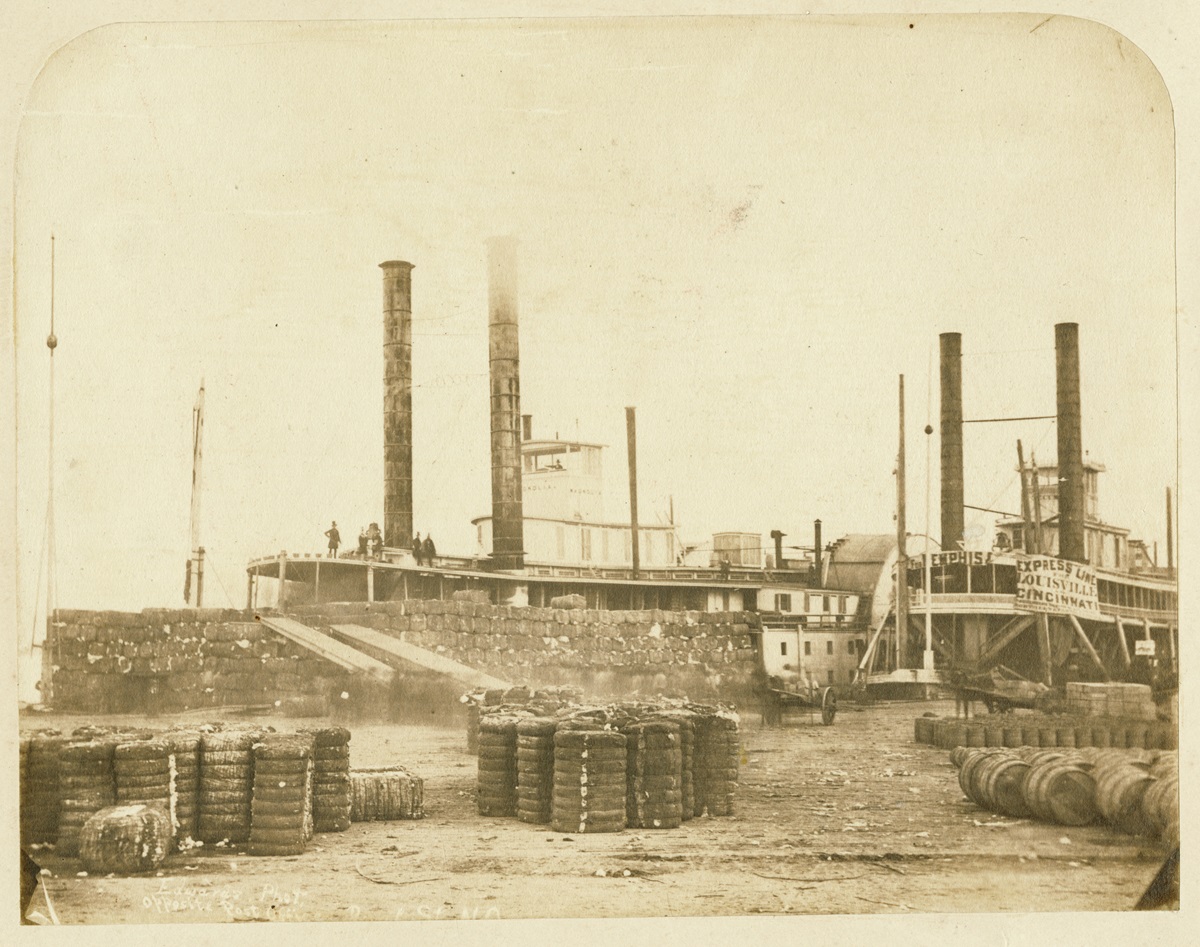

Photo by Jay Dearborn Edwards, The Historic New Orleans Collection

The steamer Magnolia at the port of New Orleans, ca. 1858.

Yet by setting foot in New Orleans, Thomas committed a serious crime. As with most southern states during the antebellum period, Louisiana law prohibited the unauthorized entry of free Black travelers from out of state, because slaveholders believed that mobile free Black people spread crime, disseminated antislavery radicalism, and inspired slave resistance. New Orleans police actively hunted free Black travelers. Discovery by police would mean expulsion; violation of an expulsion order carried an automatic one-year hard labor sentence in the Louisiana State Penitentiary. In the parlance of the twenty-first century, travelers like Thomas might be called “undocumented migrants” or be dehumanized through the slur “illegals.” In antebellum New Orleans, unauthorized free Black migrants were dubbed “contraventionists,” so-called because they had entered Louisiana in contravention of state laws.

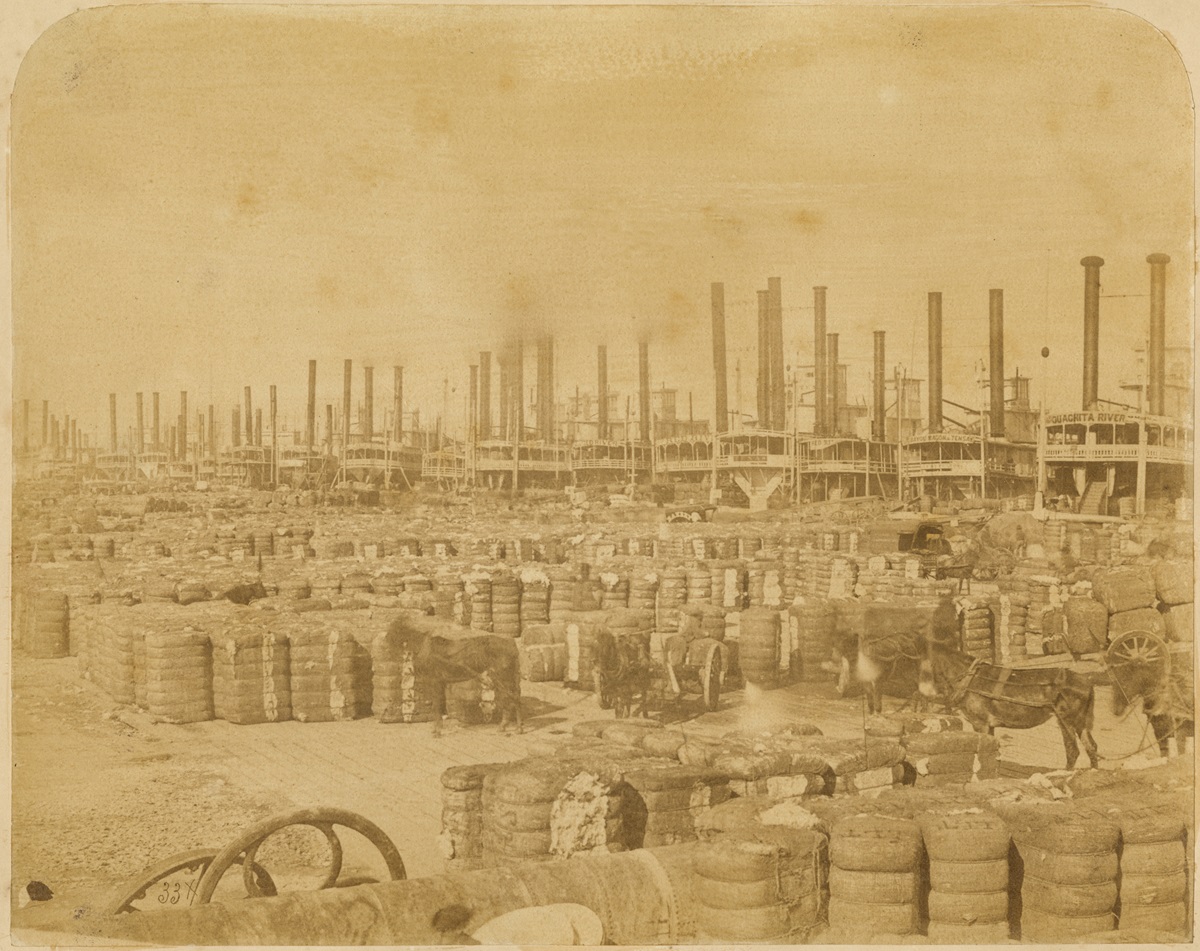

Thousands of free Black travelers entered New Orleans illegally every year. Most came during the winter, as Thomas did, when New Orleans entered a “business season” characterized by temporary wage inflation and low unemployment. Economic cycles in antebellum America were closely linked to agricultural cycles: throughout most of the country, wages peaked in late summer and early fall, as crops were harvested. Employment opportunities dried up in winter: according to the Rochester Daily Democrat of May 30, 1857, most workers were simply “left to beg, steal, or go to the poorhouse.” Yet as economies slowed to a standstill elsewhere, wages spiked in New Orleans, because winter was when sugar and cotton grown on slave plantations was brought to the city, sold, and loaded onto oceangoing ships for transport to the Northeast and Europe. During this busy season, laborers in New Orleans earned the highest wages in the country. New Orleans hummed with frenetic energy as tens of thousands of wholesalers, speculators, merchants, farmers, bankers, slave traders, entertainers, sailors, and laborers flooded into the city to buy, sell, haggle, and find work. “During the business season, nothing can exceed the bustle and activity,” reported a popular geography textbook for schoolchildren. The entire city assumed an “air of briskness,” reported the August 14, 1858, issue of the Daily Picayune. In his autobiography Thomas described a “wilderness of Mast[s]” along the levee, “vessels from all parts of the earth,” lined “three or four abreast” for “miles.” Writing in 1857, a Scottish traveler named Robert Russell estimated that New Orleans’s business season drew between twenty and thirty thousand sailors and migrant laborers, “attracted from the Northern States by high rates of wages.”

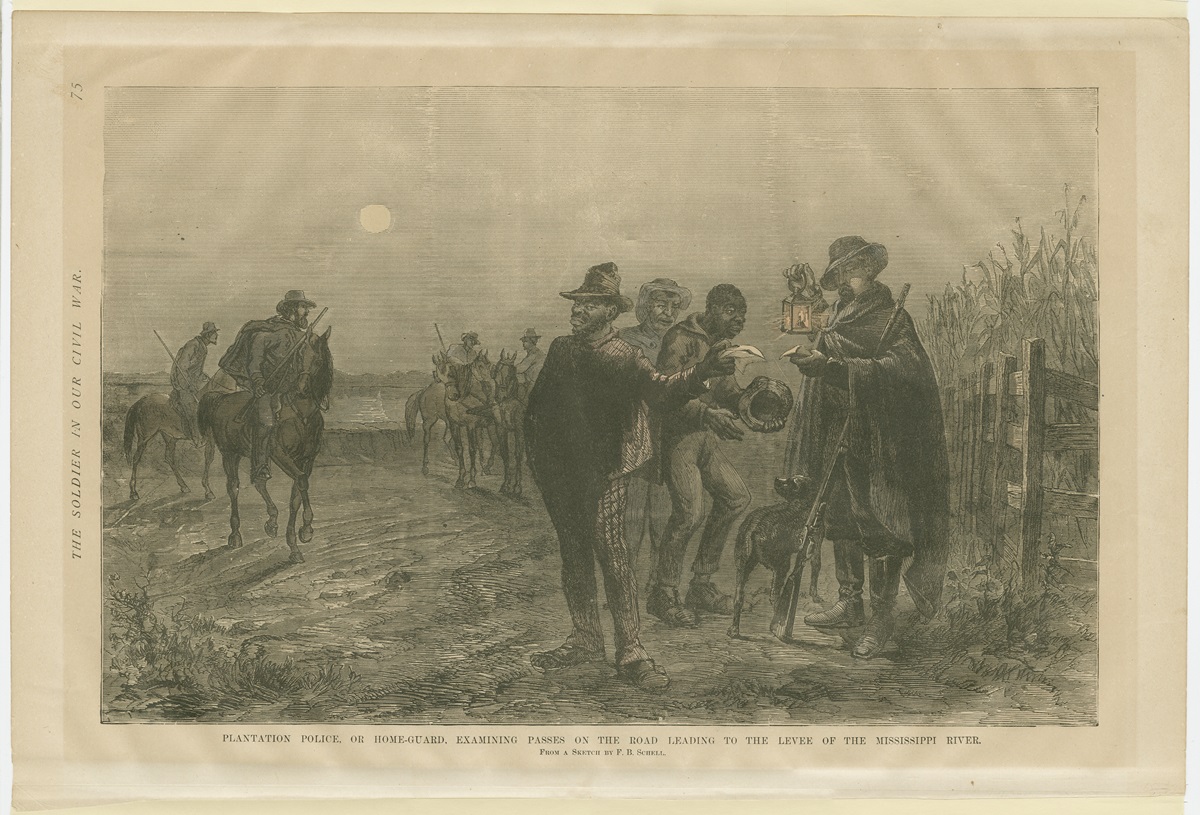

“Plantation Police, or Home-Guard, Examining Passes on the Road Leading to the Levee of the Mississippi River.” Sketch by F.B. Schell, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Free Black laborers constituted a disproportionately high share of this migrant menial workforce, because discriminatory practices and laws, endemic throughout the nation, excluded Black Americans from most opportunities for vocational training and professional advancement. While the plantation economy depended on these workers to help transport their crops to markets, free Black migrant workers were intensely criminalized by slaveholders, who were convinced that they sowed crime and posed an existential threat to racial order.

“Contraventionist” travelers had little difficulty finding work during the business season, when demand for workers spiked. Indeed, many employers preferred free Black employees, because those workers commanded lower wages than white laborers, and often were unable to sue for physical abuse or withheld wages. Still, free Black migrants had to contend with police. If approached, enslaved pedestrians were required to produce slave passes, signed by their enslaver, stating that they had the enslaver’s permission to travel. Free Black pedestrians were required to produce papers documenting their free status and local residency. Police patrolled New Orleans’s streets night and day, seizing and jailing any Black pedestrians who failed to produce these documents.

Thus one of the first things that Thomas did upon entering New Orleans was purchase fraudulent identity papers, stating that he was legally authorized to live and work in Louisiana, as protection from police. All free Black travelers in Thomas’s orbit did the same. Years later, the barber would recall a thriving underground market for forged paperwork within New Orleans, fueled by the high labor demand in the region combined with constant police surveillance. The free Black sojourner “could always find” these documents, Thomas reminisced in his autobiography, provided that he could “afford to part with twenty five dollars.”

Thomas recalled that some travelers purchased the “Christining [sic] papers of some long dead individual” and pretended to be native-born Louisianans. Others, including those who looked “as black as could be,” purchased forged documents which identified “themselves [as] Indians” or asserted “that their mother was a white woman.” Whenever arrested, these migrants would successfully petition for release by arguing that they were not legally classifiable as “Black” (under antebellum race law, children inherited the racial status of their mother). The deception struck Thomas as somewhat comical: “Fellows with white mothers came from all directions,” the barber joked.

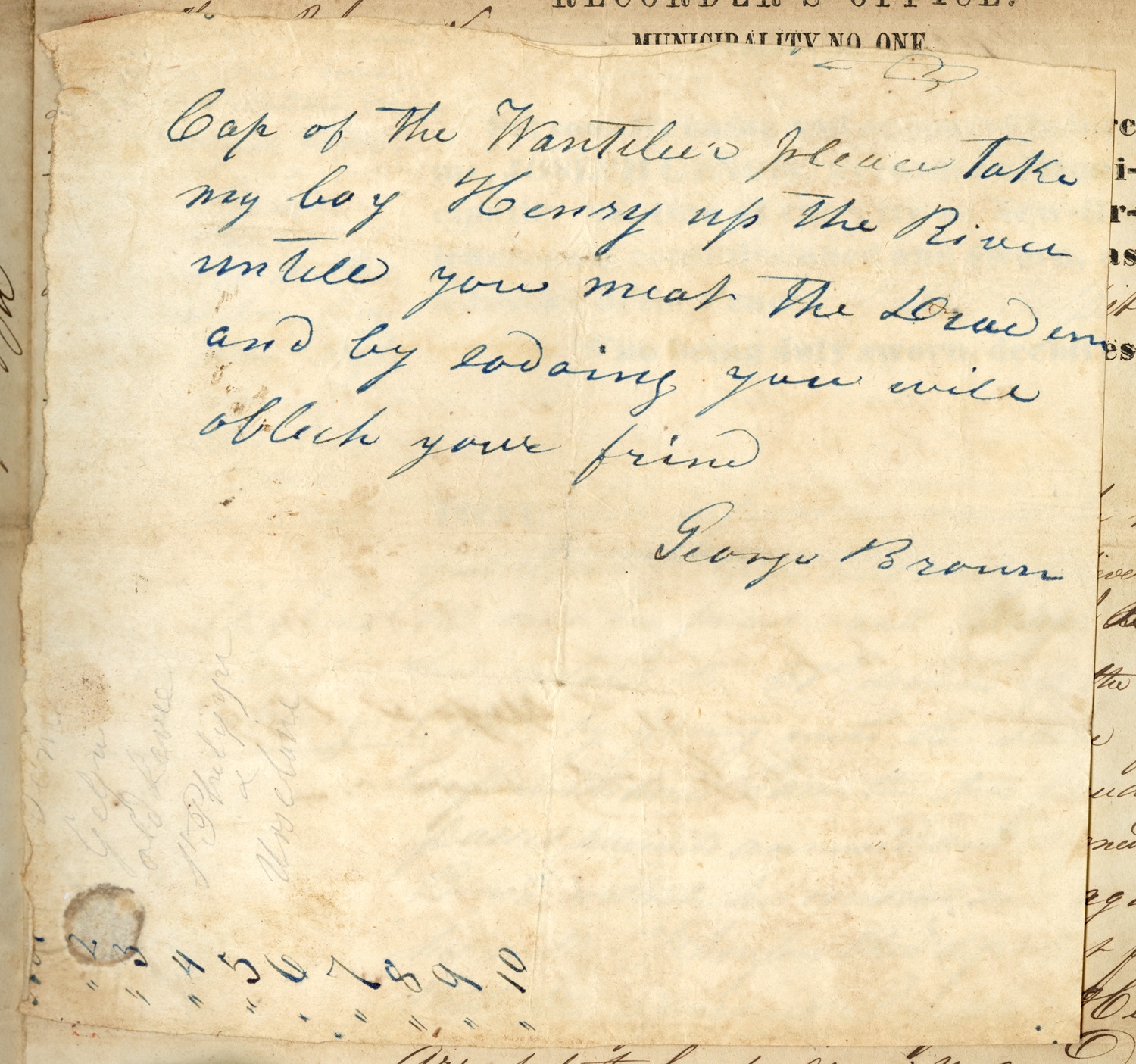

A forged slave pass entered into evidence in an 1849 court case. New Orleans Public Library.

Sometimes New Orleans police saw through the ruse. On November 3, 1841, the Daily Picayune reported the arrest ofan employee of the steamboat Nautilus for “insolence to a white man.” The employee provided identity papers that were “dated in 1804.” Recognizing that the man “was not above twenty-five years old,” police arrested him on the presumption that he was a “contraventionist” worker carrying secondhand identity papers. A “thorough investigation” of all other Black employees onboard the Nautilus yielded the arrests of three other persons, believed to be “passing under false or stolen papers.”

Police also discovered travelers who tried to falsify their racial caste. On October 4, 1856, the Daily Picayune reported the arrest of William Summers “on suspicion of being colored, and of remaining in the State” illegally. On May 3, 1861, the same paper noted the arrest of Louis Thompson, a “free colored man” who “thought the best means to avoid being arrested was to pass himself off for a white man.”

Even if they entered Louisiana legally, free Black travelers could still suffer recurrent police harassment. John Mifflin Brown, a deacon within the African Methodist Episcopal Church and a native of Delaware, was transferred to New Orleans to help grow the local mission in 1853. Though he had dutifully obtained legal permission to live within New Orleans, police detained him repeatedly, accusing him of being an abolitionist agent. Eventually, Brown purchased falsified documents, stating that his mother was white, as protection from police harassment. This gambit backfired in March 1857, when the Daily Delta reported that Brown had been arrested for “being in the State in contravention to law; keeping a school where negroes assemble for malicious purposes; and perjuring himself by swearing that his mother was a white woman.” This was Brown’s fifth arrest by New Orleans police in as many years: exhausted, he promptly fled the state.

While the plantation economy depended on these workers to help transport their crops to markets, free Black migrant workers were intensely criminalized by slaveholders, who were convinced that they sowed crime and posed an existential threat to racial order.

If they could afford it, free Black travelers paid professional counterfeiters to create forged residency papers. In 1859 New Orleans police arrested Charles Starkes, a free Black saloon keeper from Missouri, who confessed to giving a counterfeiter sixty dollars to create a forged certificate of Louisiana residency. According to the New Orleans Daily Crescent of September 30, 1859, the forger had used “chemical extraction” to remove the ink from a set of residency papers that had originally belonged to a free Black Louisiana native named Lorenzo Dow, who had been killed in a street brawl one year earlier.

Sixty dollars for residency papers amounted to a small fortune in an age when menial laborers often earned as little as a dollar per day. There was a cheaper strategy: to purchase forged slave passes, and pretend to be enslaved.

The concept of a free Black person voluntarily pretending to be enslaved, in an age when Black freedom was rare and under constant attack, seems counterintuitive. But the strategy was not uncommon among free Black migrants seeking work within the city. Indeed, Louisiana’s attorney general declared suppression of the practice to be a top priority of Louisiana law enforcement in 1856. “The debased free negro of the Western States, anxious to better his condition by locating in New Orleans, obtains a forged pass describing him as a slave, and dated in a Slave State, permitting him to come to New Orleans,” the attorney general complained in his annual report to the state legislature. Under the pretense that they were enslaved, “gangs of free negroes” from out-of-state “engaged at work on the Levee . . . they come to New Orleans in the winter, find ready employment, and when the business season is over, they return to the North.”

In disguising themselves as enslaved people, these migrants took advantage of a practice, common in many southern cities, known as “hiring out.” Under this arrangement, enslavers seeking to maximize their profits would force enslaved people to sell their labor on the open market, on the understanding that they would regularly deliver their wages to the enslaver. Free Black migrant workers recognized that these hired-out enslaved people were often subjected to less police scrutiny, and enjoyed broader mobility, within cities: by forging slave passes stating that the bearer had been “hired out,” free Black workers minimized their risk of molestation while traveling in search of work.

Loading steamboats at New Orleans, ca. 1860. Photo by Jay Dearborn Edwards, The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Periodically newspapers reported on the discovery of travelers who deployed this strategy. On November 11, 1859, the Daily Picayune reported that police had raided the steamer Northern Light, arresting “Twenty blacks” whom the officers identified as free but who “represented themselves as being slaves, duly authorized by their masters to work on board of the boat.” On February 28, 1861, the Daily True Delta reported that police had arrested a man along the levee who initially identified himself “as the slave Wallace, of J.P. Horbeck, of Memphis” but who later “admitted he was a free negro, traveling on a false pass” that he had purchased from a stranger on the levee. In 1847 police frisked a Black woman named Mary Carter shortly after her arrival from Missouri. According to the Daily Picayune of October 24, 1847, the search revealed two contradictory sets of documents: a slave pass stating that she’d been given her “liberty as a slave to hire herself out,” and freedom papers identifying Carter as a free woman from North Carolina. Police immediately searched all Black passengers and crewmembers onboard the Little Missouri, discovering eight other Black women and men “who claimed to be slaves, but who were arrested, supposing them to be free.”

In the twenty-first century the policing of undocumented migrants is once again an issue of great political import. Proponents of stricter policing policies argue that undocumented migrants spread crime, destabilize society, and undermine the rule of law—arguments similar to those advanced in opposition to free Black interstate migration during the antebellum period. Immigrant-rights advocates argue that undocumented migrants have a net-benefit impact on their local communities and economies, citing data that indicate they are significantly less likely to be incarcerated for property or violent crimes than their native-born neighbors.

Antebellum politics are not equatable with twenty-first century politics. But we would do well to note the parallels. Once again the criminalization of a mobile, “undocumented” workforce has yielded an underground labor market wherein workers are extremely vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. Ultimately this vulnerability serves the economic interests of both employers and consumers by driving down wages and prices. The public’s willingness to tolerate this exploitative dynamic depends upon the criminalization and racialization of that workforce—processes that are closely intertwined. Faced with these conditions, workers create and circulate subversive strategies.

John K. Bardes is an assistant professor of history at Louisiana State University. He is the author of The Carceral City: Slavery and the Making of Mass Incarceration in New Orleans, 1803–1930 (forthcoming from UNC Press, 2024).