Victor Séjour, La Société des Artisans, and Afro-Creole Literary Protest

An excerpt from Creole New Orleans in the Revolutionary Atlantic, 1775–1877 by Caryn Cossé Bell

Published: November 30, 2023

Last Updated: February 29, 2024

LSU Press

Nowhere in the United States did the Age of Democratic Revolution exert as profound an influence as in New Orleans.

Near the time of Lafayette’s visit, the city’s free Black veterans-turned-artisans founded La Société des Artisans in the mode of the Francophone Atlantic’s French and Haitian cénacles (literary societies). In these tightly knit societies, Romantic authors shared their work, protested injustice, and formulated resistance strategies. In New Orleans as in Paris and Port-au-Prince, cénacle writers became active agents of change by assuming a broader, quasi-political role within the free Francophone community of color.In one of the many Afro-Creole works of protest literature authored in the city prior to 1840, an anonymous veteran with the pseudonym Hippolyte Castra attacked the treatment of free soldiers of color in the aftermath of the Battle of New Orleans. The poem, “The Campaign of 1814–15,” is believed to have been recited at a Société des Artisans meeting before veterans-turned-artisans such as Sylvain d’Aquin. At the approach of the British, the author wrote, white soldiers urged men of color to “Come, let us conquer, my brothers.” After their victory in “this terrible and glorious combat, all of you shared a drink with me and called me a valiant soldier.” Soon, however, “fierce looks” replaced the “gracious smile” and the veteran soldiers of color became “an object of scorn.”

In providing a literary forum for free New Orleanians of color, La Société laid the foundation for a stellar African American literary tradition that has thrived into the present-day. With a Francophone membership that included whites as well as men of color, the organization yielded its first prodigy in the person of Victor Séjour. The aspiring young writer debuted his work before a society audience that included the refugee officers and soldiers of the Second Battalion. The artist’s father, Louis Victor Séjour, was an officer in d’Aquin’s unit and was, like his commanding officers d’Aquin and Savary, a native of Saint-Marc [Saint-Domingue] who entered Louisiana as a member of Savary’s garrison in the 1809 migration. By 1822, he operated a small dry goods store. His young son’s extraordinary talent impressed the organization’s interracial membership and sometime between 1834 and 1836, the teenage Séjour left New Orleans for Paris.

In France in 1837, the abolitionist journal Revue des colonies published Séjour’s “Le Mulâtre” (The Mulatto), the first short story by a United States African American author. Set in Saint-Domingue, the tale is exceptional for its straightforward depiction of slavery’s horrors. In subsequent works, Diégarias (Jew of Seville), accepted by the Comédie Française in 1844, and The Fortune-Teller (1859), Séjour dramatized the dangers of multiethnic identity in a society divided by race and religion. Two other manuscripts of a protest nature, l’Esclave (The Slave) and a drama based on the life of abolitionist John Brown, have yet to be recovered.

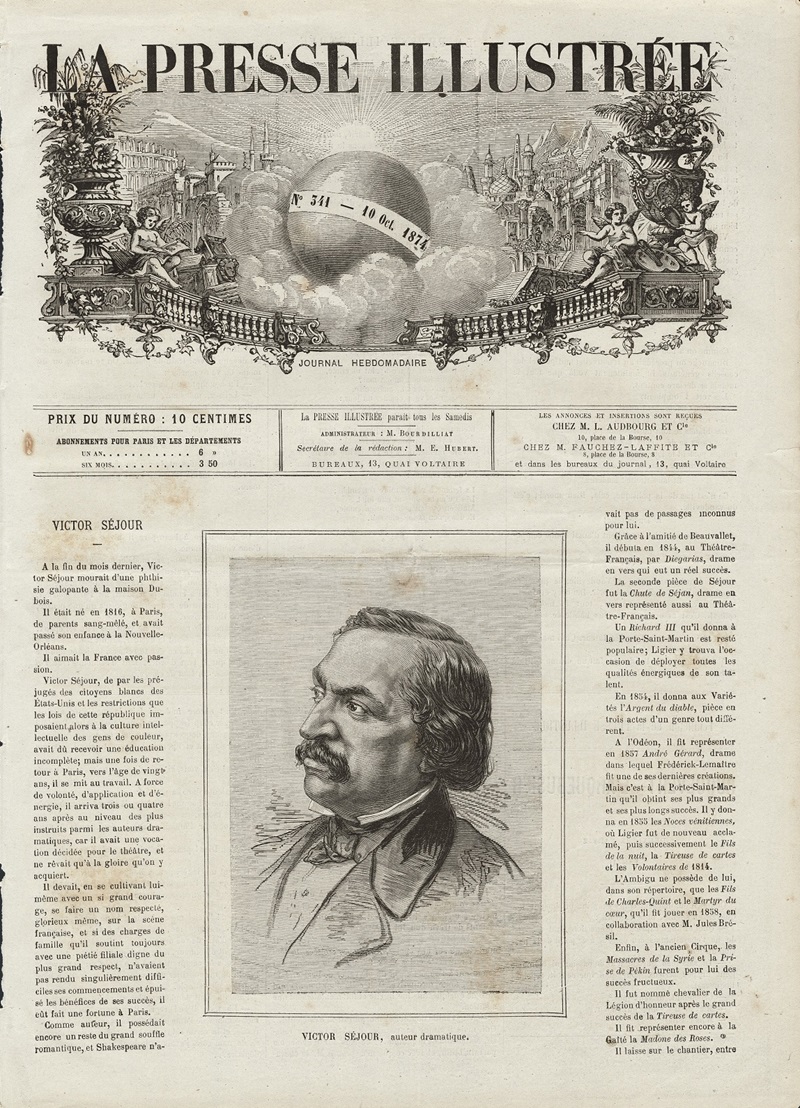

In Paris, Séjour’s skills as a dramatist propelled him to critical and popular acclaim. Twenty of his twenty-two plays were performed on Parisian stages between 1844 and 1875 with three of his productions being performed simultaneously in the French capital. In New Orleans where Diégarias was well received in 1847, white supremacists dissed a proposal to honor the playwright with a medal recognizing his success.

October 10, 1874, edition of the Paris newspaper La Presse Illustrée, featuring Séjour’s portrait and obituary. The Historic New Orleans Collection.

In his 1858 drama Le Martyre du Coeur (Martyrdom of the Heart), Séjour featured a Black character in a major role. The play weighed the outcomes of emancipations in Haiti, France, and the British Caribbean as models for slavery’s abolition in the United States. In the end, the dramatist depicts the British model of abolition through peaceful political reform as the best way forward for North America. Séjour’s artful strategy allowed him to steer clear of Napoléon III’s pro-South sympathies while upholding his dedication to the antislavery cause. When Séjour died in Paris in 1874, the French memorialized his genius by burying him in the city’s famed Père Lachaise cemetery.

Beginning with their illegal entry into the city in 1809, Louis Victor Séjour, the Savarys, and their fellow veteran soldiers repeatedly ignored state and city laws designed to relegate them to an inferior status. The international character of La Société des Artisans, a cénacle with a politically charged mission, represented a clear and present danger to the interests of white slaveholding planters. The society’s multiracial membership challenged the spirit if not the letter of local statutes restricting contact between whites and people of color. Still, conservative city and state officials refrained from a crackdown on La Société despite their intense hostility to the mere presence of the free men of color. Their caution might be attributed to the possible presence in the organization of well-connected whites like d’Aquin and his powerful allies in the refugee population.

EXCERPT FROM:

Creole New Orleans in the Revolutionary Atlantic, 1775–1877

by Caryn Cossé Bell

$45; 344 pp.

Louisiana State University Press

October 2023